We’re Lost in Music

‘THE LAST GREAT Album of the Decade’ is a group exhibition I co-curated with Sheena Barrett that opened at The LAB in March. As the title suggests, the exhibition touches upon the decline of the music album as an artform, but ultimately the main intention behind this endeavour was a desire to explore popular music’s power to connect people, through an investigation of the intersections between musical culture and the visual arts. Preliminary conversations began in 2017 and – over the course of two years – each of the invited artists explored their own relationships with music, eventually producing work that served as testament of music as catalyst for social exchange and the expansion of boundaries between artforms. An early conversation with Declan Clarke informed and ultimately provided the genesis of the exhibition. Having discovered a photograph featuring Clarke, taken outside the National Stadium in 1991, I initiated a conversation that informed the curatorial approach. Clarke had extremely vivid recollections of gigs he’d attended in Dublin in the early ‘90s. These memories were presented as wall texts in the exhibition, alongside an array of ticket stubs and t-shirts collected all those years ago.

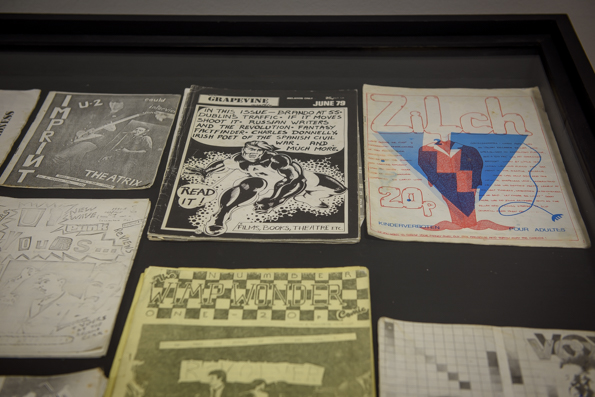

Taking on the character of relics in this context, each object held personal memories, as well as wider sociological significance. They represent a seminal moment in the transition of youth culture in which popular musical tastes moved rapidly, from indie rock and electronica to the emergence of rave culture. The image that we ended up using as the promotional ‘avatar’ for the exhibition was a photo of Clarke taken surreptitiously by his late father in 1991, in which he is surrounded by his posters and cassettes. The image underscores how the journey of discovery and belonging for the adolescent in musical worlds can provide a lifelong source of enthusiasm. In addition, a selection of zines, dating from 1978 to 1981, from the Brian McMahon Archive (Brand New Retro) offered insights into the range of music-related printed matter that was once produced and disseminated in Ireland. The quality of these zines varied hugely and the determination and desire to contribute enthusiastically to this dialogue far outweighed the technical means of production available during that period.

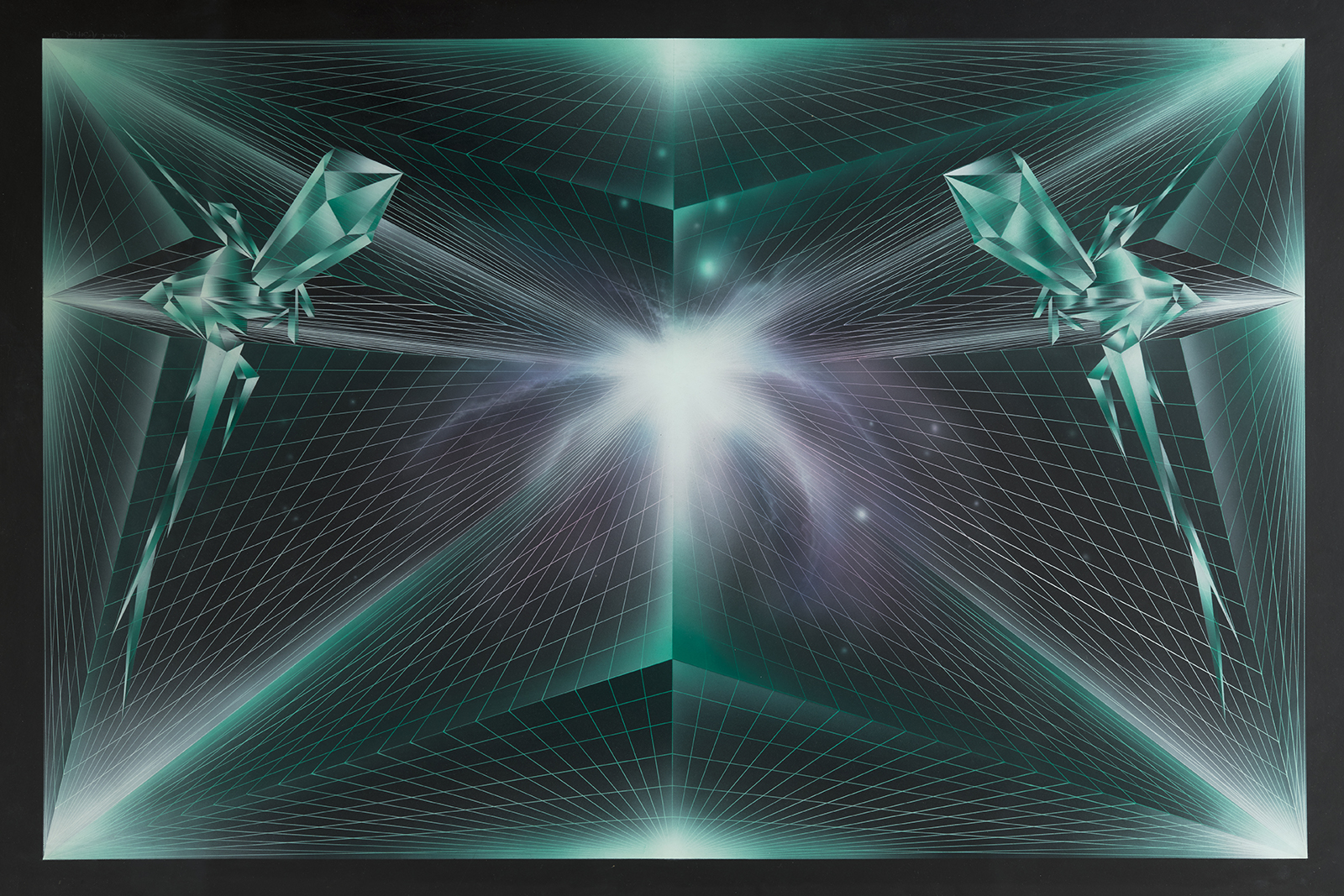

Although the outcome, aesthetic and milieu were different, the potential and power of the DIY ethic was also evidenced in a series of photographs taken by Anne Maree Barry in the early noughties. The underground beach parties that took place in North County Dublin in the summer of 2003 emerged from a culture of self-organisation and self-sufficiency, with an emphasis upon inclusion and togetherness, facilitated through music. The parties captured in Barry’s photos were (and still are) relatively rare in a city like Dublin, where overzealous law enforcement belies a provincial and conservative leadership who view nightlife and club culture as valueless and deviant. While the aforementioned contributors focused upon the material remnants and the social milieu that forms around music, others responded to and ‘inhabited’ music more formally, producing work concerned with characteristics that might be aligned with the more abstract properties of music. Ostensibly, Alan Phelan’s visually striking installation is made from material usually employed in photoshoots.

In this instance, the RGB (red, green and blue) curtain was conceived as the backdrop for a music video, with the aim of creating a setting for a narrative – a site of possibility. To accompany Phelan’s mise-en-scène, a piece of electronic music was composed and presented on the opening night, functioning as an excerpt of a soundtrack to a film not yet made. A new body of sculptural assemblages by Cliodhna Timoney are named after nightclubs in the town of Letterkenny, County Donegal. Some of these clubs – such as The Golden Grill, The Pulse and Voodoo – flourished in the mid to late ‘90s and are now defunct and in a state of dilapidation. Timoney’s sculptures are both a homage and formal interpretation of these environments of music and hedonism, where people go to lose themselves in dancefloor catharsis. Scattered throughout The LAB, Timoney’s variegated assemblages suggest the detritus that remains in the aftermath of the party; when the lights turn on at the end of the night and dazzle us.

Both Phelan and Timoney responded directly to one of the more interesting aspects of the LAB’s main gallery space – its height. Both created works that could be viewed from different levels and which created an immersive experience for viewers. Several live events punctuated this exhibition, and these were programmed to coincide with MusicTown, the annual festival led by Dublin City Council and Aiken Promotions (5–21 April). One of these was a walking tour on 14 April, led by local historian Dónal Fallon. The tour responded to and engaged with Dublin’s architectural fabric and encouraged consideration of the informal organisations and social structures that once emerged around – and within – the city’s music scenes. Beginning at The LAB, the walking tour took a circuitous route through the city, visiting several venues and sites of musical and social significance. In the process of curating this exhibition, a touchstone was Dan Graham’s seminal video essay, Rock My Religion from 1985, which I would encourage all readers to watch. Made at a time when convergences between visual art and music were reaching unprecedented synergistic peaks, Graham’s essay, aimed primarily at a visual arts audience, sought to underscore the importance of certain musical genres within the preceding decade.

Essentially, Graham’s video essay addresses how popular rock music facilitated certain forms of enlightenment and egalitarian togetherness. This position is communicated in the closing lines via the proclamation that “if art is only a business, as [Andy] Warhol suggests, then music expresses a more communal, transcendental emotion which art now denies”. Like Graham’s film, this exhibition at The LAB revelled in the sacral aspects of popular music that have (perhaps necessarily) been discarded or relegated from the sphere of visual art. This group show considers, quite seriously, the profound devotion of the fan, the surrender to cultish following, the fetishistic interest in memorabilia, the communality of the sweaty fray, and perhaps, most importantly, the desire to get lost in (what Roxy Music refer to as) The Thrill of it All.