Untitled (Winter)

Dearest P.,

Thank you for your letter which evidently I have received, despite your misgivings that it may not reach me. I’m still building my little house deep in the wilderness and although there is still much to be done, progress has ceased for winter. Fortunately, construction of the shelter was completed before conditions really deteriorated, so I’m insulated from the increasingly inclement weather. Although I still believe that living off of the electricity grid has been a wise decision, recent months have been extremely challenging, not least because I still haven’t succeeded in setting up the PV system and am therefore without power. I’m currently cooking on a camp stove and using propane lamps and heaters for light and warmth. It’s going to take a long time before I achieve something even approaching comfort but I’ve no regrets about renouncing my previous life. The decision to eschew the shallow, superficial existence I was leading was entirely necessary. Had I continued on the path I was on, I’d inevitably have found my- self complying with middle-class notions of respectability and conforming to countless conventions I’ve spent my life fighting against.

I read Walden several years ago. It’s a rambling book and I don’t recall it in detail but I do remember appreciating how solitude and self-sufficiency are advocated throughout as a means of achieving psychological clarity and spiritual fulfilment. Although Thoreau only dropped out of society for a couple of years, he certainly seemed to have found transcendence in that period, and the book that emerged from his time spent living as a hermit has undoubtedly inspired many others to follow a similar course. I suppose Walden could be considered one of the first books to popularize the archetype — embraced by so many in the 1960s — of the individual who abandons urban domesticity in pursuit of an independent, sustainable, and self-sufficient lifestyle. Another important aspect of Thoreau’s book is its promotion of civil disobedience — not only as a human right, but as an obligation. Nevertheless, despite its many merits, Walden will forever be inextricably linked in my mind with Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. There are, after all, so many parallels between the secluded existence led by Kaczynski and the way of life of which Thoreau writes about in Walden. One sometimes wonders if Kaczynski was perhaps self-consciously emulating his literary predecessor in some way. Either way, it is possible to see Kazynski’s pursuit of total self-sufficiency as either a twisted distortion of Thoreau’s idyll or else the ideal promoted in Walden brought to its logical conclusion.

Kaczynski began his career in 1967 as a prodigious mathematician, lecturing at Berkeley when he was still in his mid-twenties. After two years of teaching, Kaczynski underwent what was ei- ther an epiphany or descent into madness. He assumed a radical position regarding the direction he believed society was headed. In particular, Kaczynski was concerned with how technology was blindly embraced in the Western world, with little consideration given to its potential consequences. Kaczynski renounced his previous life as a mathematician and relocated to one of the most desolate areas of Montana. There, he built a small cabin and lived in almost total isolation, hunting animals, growing vegetables, reading, and exploring the surrounding countryside. In writings and interviews Kaczynski reflects fondly upon this time, though his writing does reflect some sense of the misanthropy that would become a major motivating factor in his later actions. Kaczynski’s philosophy (which has been the focus of much analysis by psychologists) was not so much anti-government as it was anti-technology. In 1978 Kaczynski began a sporadic seventeen-year-long attack on the individuals and organizations he saw as representative of the technocratic status quo. From his isolated cabin in the woods, Kaczynski became the archetypal anarcho-primitivist, producing handmade bombs that were often inserted into rustic wooden boxes alongside shards of sharpened wood that would function as shrapnel. It’s these details that make his obsessive mission so intriguing.

Most of these bombs were disseminated via the postal system to universities (including one he had previously worked at) and airlines, targeted because they promulgated the technological systems Kaczynski believed were insidiously dominating and de- spoiling the earth. In addition to letters written anonymously by Kaczynski, his motives and objectives were outlined in his extensive manifesto published in 1995 in The Washington Post and The New York Times. The manifesto provides a thorough explication of how the Industrial Revolution and the dependence upon technology which followed it have had disastrous consequences for the human species and the ecosystem of planet Earth. It’s an un- deniably compelling—although rather paranoid—argument which proposes that the realms of science, government, and education have utilized forms of technology that subjugate and control the masses in subliminal and irreversible ways. From today’s perspective, much of Kaczynski’s writings seem prophetic. In them, he describes the technological webs upon which we are so reliant as comprising a hostile system in which all parts are dependent on one another; a system guided not by ideology, but by technical necessity. While the violent acts perpetrated by Kaczynski were of course abhorrent, they were carried out earnestly, in a sincere effort to bring down the system that has materialized in the period of time since he was jailed in 1996. From the perspective of the present day, one cannot simply dismiss his words as the mis- anthropic ramblings of a psychopath. I must admit that many of his opinions resonate with my own. It would seem Kaczynski was on a one-man mission to slow the inevitable progress of “techno- logical slavery,” and though he didn’t succeed in bringing about a collapse of the system he so despised (it would never have been possible), he did evade arrest for seventeen years. Revisiting the case in 2014, one can’t help but imagine how it could never have occurred. Today, the level of surveillance is too great and the grid of communications too efficient to permit an individual to wield such a sustained attack on the world.

The interviews conducted with Kaczynski after his arrest often express outrage at the way in which his environment was being steadily devastated. In his view, this destruction of nature was ultimately tantamount to the destruction of liberty. For Kaczynski, technological progress was inextricably connected with the annihilation of the environment in which he had found happiness. In his writings, he even mentions the desire to exact revenge upon the society that is unwaveringly destroying and despoiling the earth. It would seem that living in complete isolation in the depths of that dense forest provided Kaczynski with what Thoreau called “the tonic of wilderness.” The notion that one can find peace of mind via submergence in the natural world is some- thing that interests me deeply. About a decade ago, when I was walking in some hinterland, I realized for the first time that the only place I had ever felt something truly vital was when I was surrounded by the profusion of unbridled wilderness. It was around then that I—someone who had always identified as agnostic—began to view nature from a pantheistic perspective. What I mean is that being here in the wilderness instills within me a sense that there is a life force, something almost divine, tangible in the natural world. Since relocating here, the translated writings of Hildegard von Bingen have become an important touchstone for me, assisting me in my efforts to view the world through a new lens. These writings are dense and often cryptic but I am in awe of her mind, which was undoubtedly that of a radical. Although she was obviously devoted to the Christian cause, her approach was singular and it was ultimately the life force visible to her in the natural world that she worshipped. In O Viridissima Virga Hildegard writes of “the greenest branch” as not only beautiful, but sacred—and worthy of worship—because it is a manifestation of the subtle energies that unify and animate all living things. Some might view Hildegard as a kind of proto-ecofeminist in the way that she focuses explicitly upon the destruction of the natural world in several of her writings and repeatedly emphasizes the notion that Earth is a “mother.” She writes: “the elements are complaining with strident voices to their creator. Confused through the misdeeds of humans, they are exceeding their normal channels, set for them by their creator through strange and un- natural movements and energy currents.” Inherent in this passage is the notion that some sort of divine justice will be meted out to the inhabitants of Earth who have failed to act as custodians to Mother Earth. Hildegard prophesizes in the same vein as Kaczynski and her vision is apocalyptic. She, too, foresees turbulence, upheaval, and chaos: degeneration and collapse will occur as a result of the unrelenting destructive forces of humankind.

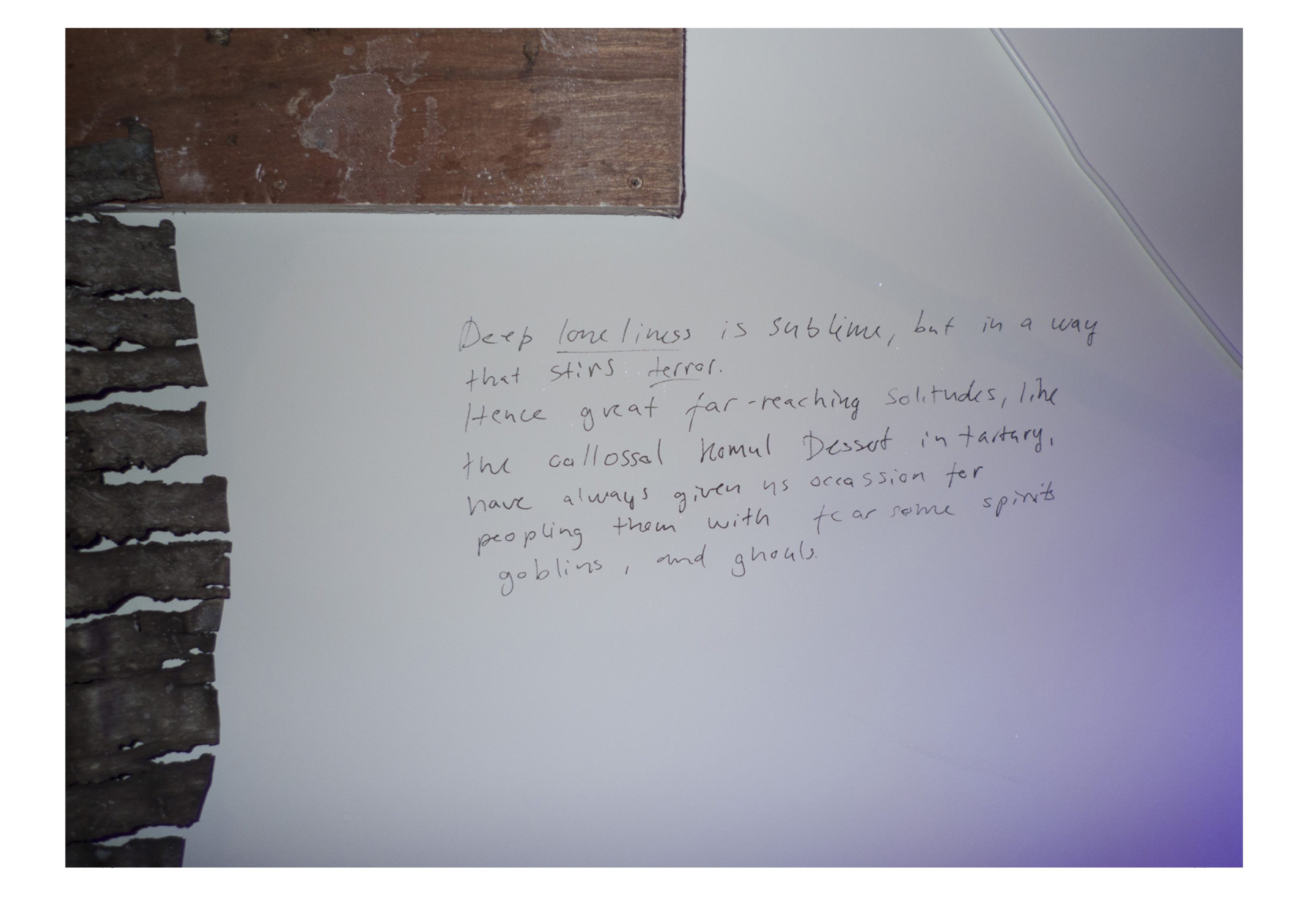

During the period of her life when she was living in silence and solitude, Hildegard formulated a cohesive view of the world and, it could be said, achieved the meditative state that allowed her to “find God.” While it may be possible to achieve some sort of transcendence via solitude, it is my belief that it is also required for the most basic aspects of human functioning. Solitude is a vital component of mental functioning that makes it possible to process the sensory bombardment one encounters on a daily basis. Yet paradoxically, it would seem that solitude and silence have never been harder to find or less appreciated as crucial, despite the fact that we may need them more than ever in this accelerated age. For it seems to me that some of the most profound human experiences and thought processes occur when we are alone and have nothing to do with interpersonal encounters. For me the decision to move out here was less important than the decision to disconnect from the communication networks that have become such an integral aspect of contemporary life. In order for me to truly achieve the seclusion and the silence that I require, it was necessary for me to sever all ties with these networks. The telecommunications that have become compulsory components of everyday life have dissolved the isolation that physical distance could give. I was preoccupied by these thoughts in the months before I moved here. I became acutely aware that in this technophilic age of ours, seeking solitude is looked upon with suspicion as though it were some kind of aberration, as if being alone is often confused today with loneliness.

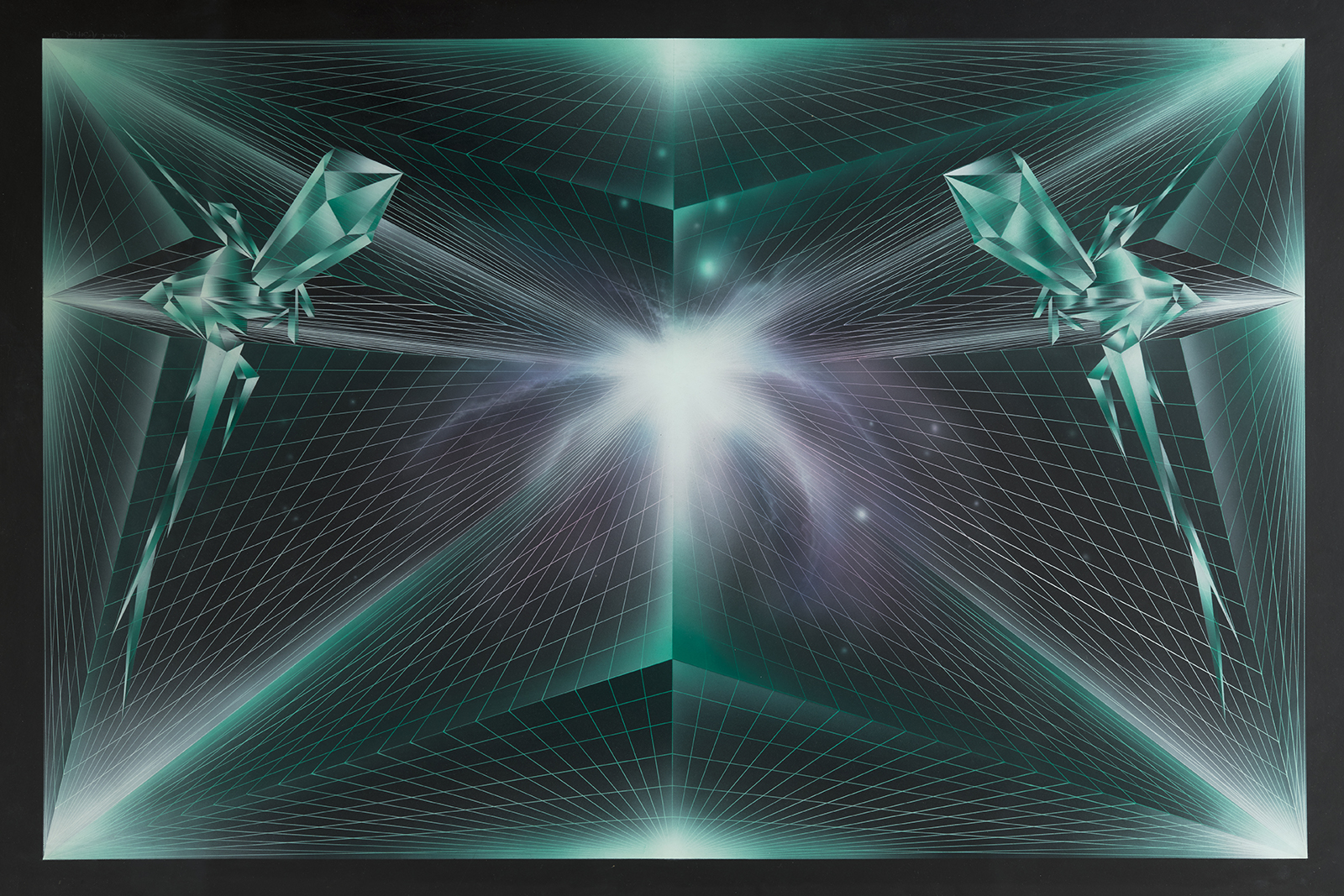

I thank you for writing to me out here. I am grateful and willing to communicate with you if it makes you feel better about my being here. However, I’d rather not think or talk about the person that I used to be. I’ll admit: there were some truly special times in the past and I do occasionally reflect upon them with a certain fondness. However, even though I enjoyed the frisson and the frivolity of that phase of my life, everything and everybody (including myself) began to seem so horribly hollow. Out here I feel awake again; silence and solitude have rejuvenated my perspective and just being alive is enough. As I told you before, I know what I do not want to become and I have moved away from it. Out here in the woods, I will attain clarity and make myself open, so that I can finally become a vessel for cosmic information.

Love, C.