Interview: Bob and Roberta Smith

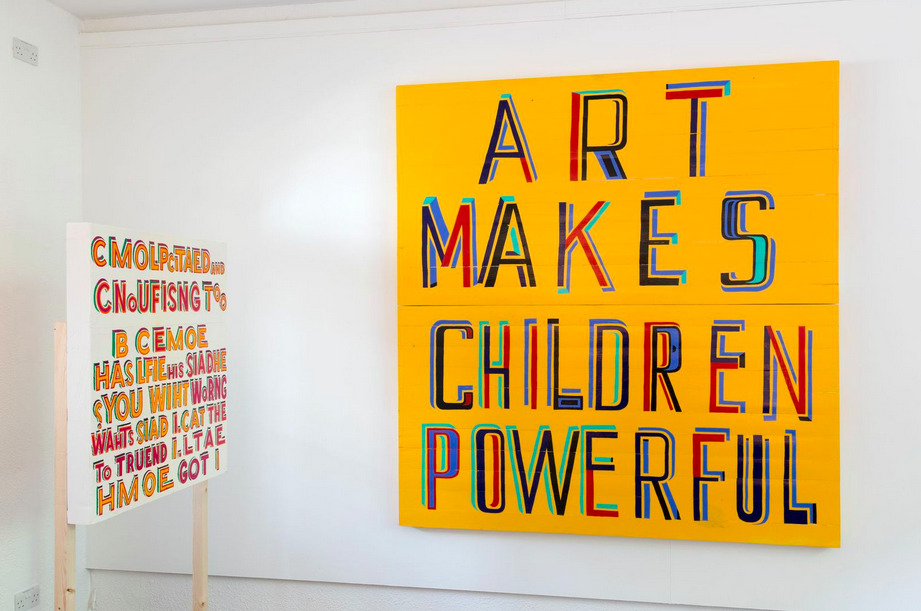

In the summer of 2013, the first major solo presentation of work by Bob & Roberta Smith took place in Ireland. The exhibition titled Art Makes Children Powerful was curated by Josephine Kelliher of the Rubicon Gallery, Dublin, and Anna O’Sullivan of the Butler Gallery in Kilkenny. While the exhibition at the Butler Gallery constituted the core of the project, there were several installations in other locations throughout the city of Kilkenny. The many facets of the exhibition, comprising paintings and sculptural environments, were conceived to respond directly to the specifics of the sites in which they were installed. There was clearly an emphasis to encourage viewers to access and to feel a sense of ownership over the various public spaces used by Smith. The dialogue below is an excerpt from a conversation that took place between Smith and Pádraic E. Moore in the days following the opening of the exhibition.

Pádraic E. Moore: The walk-through that you gave the day the exhibition opened provided excellent insight into your work. During the course of your introduction you mentioned several historical figures that have had a significant impact upon you and the development of your work. Obviously, the influence Hannah Arendt has had on your thinking is manifest explicitly in this show, however, I am curious to know if there are any artists or thinkers other than those referred to in this exhibition who have really influenced your approach to making work who you think are important to acknowledge? I’m as interested in attitudinal influences as much as visual or formal influence.

Bob & Roberta Smith: This is of course a difficult question to answer, not least because my influences are so varied and polyglot. I was certainly significantly influenced by the atmosphere that I encountered during the period I spent living in New York in the late 1980s. It was then that I came into contact with the work of artists such as Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer who have had a significant influence upon my work. However, in terms of British art, one person who was truly inspirational to me—as much for her character as for her work—would definitely be Helen Chadwick.

P: She certainly is an interesting figure and one who has probably been overlooked as a result of her early death. The work she made at the beginning of her career with a photocopier is particularly interesting, and there was also great series of meat abstracts. There seems to have been something of a resurgent appreciation of her work in recent years.

B & R: When I was a student at Reading University, one of the first exhibitions I saw that really turned me on was by Chadwick. Sitting on top of a Canon photocopier using a dead goose and fruit she created an incredible artwork that evoked Leda and the Swan.[1] She also produced another work that had a significant impact upon me, which comprised a glass pillar of decomposing vegetables.[2] That piece had to be deinstalled prematurely because it was feared that it might explode. Seeing her work was significant for me because it encouraged me to not work within any one particular canon. At that time I had been making paintings and was slowly starting to make installations. These installations were of course very different from Chadwick’s work—I have always been more into the aesthetics of Pop art. Ultimately, it was Chadwick’s attitude and approach that I found most interesting. I see in her work that she is saying something very powerful.

P: Perhaps we can we talk a little about your use of language as medium? You utilise text in a way that is didactic, almost propagandistic. And formally, the presence of the hand is always evident. Although I know comparisons are unnecessary, I see your use of text as polarized from that of Lawrence Weiner whose phrases operate purely on spatial and poetic levels. Do you see language as a material in itself, or is the message more important than the medium? Is your main aim to communicate a position, or are you also interested in the formal and painterly aspects of the work?

B & R: The fundamental difference between my work and that of someone like Weiner is that I like making work that uses language to express political ideals—particularly those ideals about democracy. Ultimately, I don’t take a single hard line view in my work with language, but try to take multiple approaches. Personally, I do like Weiner and his activity, but I would not want to be a sculptor of language. I want to tease things out and not really direct and be more rhetorical. I am sometimes accused of being insufficiently rigorous. I am interested in the difference between what is said and what the intended meaning is. I suppose I’m influenced by the creativity of someone like George Orwell and his idea of ‘doublespeak’, which is when every politician tells you something and they mean the exact opposite. I suppose in some way we all do this because language is such an insufficient bag of tools. It is, however, a rich and very interesting bag of tools to use. I’m certainly interested in the difference between language that is used and its intended meaning. When I make a painting, I try to persuade the viewer that the message in any given slogan means exactly what it says. In terms of language, I’m also extremely interested in the potential for poetics. I guess that’s why I’m such a fan of writers like Sylvia Plath, Samuel Beckett, and of course Mark E. Smith of The Fall. One could say that in the case—in all of these cases—language is almost sculptural.

P: While your object-based work is stylistically distinctive, your practice also extends to a diverse range of processes and is also often deeply rooted in dialogue and exchange. This is something that really struck me during the walking tour you led around various locations in Kilkenny where your work is installed. It’s clear from several past projects, that engaging directly with people and allowing this to enter into your work is an integral aspect of your practice. There were some interactive elements in your Kilkenny show. It is clear that you want to challenge the viewer and encourage them to question certain things. However your work retains a stylistic and physical integrity. With this in mind I wanted to ask you your thoughts on the way in which certain notions of what might be termed ‘interactivity’ have become important to visual art in recent decades. One manifestation of this might be seen in the way that relational aesthetics became a kind of affectation among artists who wanted to somehow affirm that their work was ‘interactive’. While the intention of much of this work may be to involve an audience and remind them of their own ‘agency,’ I believe that fact is that interactive can often alienate the audience while also reducing the autonomy of the artist. I think that your work strikes a balance. Would you agree that much of what is conceived and intended as interactive often fails in its intentions and can actually have damaging repercussions?

B & R: It’s certainly a complicated issue but I think you are absolutely right about much interactive art being ineffectual. However, that said there several artists such as Piotr Uklanski or Rikrit Tirivanija for example whose early work was initially admirable in intention. I think problems really arose when Nicolas Bourriaud published his series of—ultimately speculative—essays, and people responded to it as though it was a manual for making art. Certain mannerisms definitely entered into art after Relational Aesthetics was published. I suppose one of the main problems with making work that proclaims to be ‘relational’ is that the terms of agency are often predefined. Many of my thoughts on this issue are shaped by the fact that in addition to my work as an artist, I also work as an educator. In this role it’s my intention to create situations in which I act as a catalyst as opposed to dictating what people do. I must say though that while I am critical of what might be called a ‘relational aesthetic mannerism’, I have much respect for him because he is a genuine intellectual, a type that are becoming increasingly rare. Bourriaud curated Altermodern at the Tate, which was an excellent exhibition. Back to the issue of relational aesthetics though, I do think that many funding bodies became great supporters of work that utilised methods with an explicit social agenda. That said, I am supportive of young artists being funded for experimental work because some of the ghastly and patronizing work may actually lead to something excellent. What I mean is, I am keen on younger artists with more experimental practices to receive funding.

P: I suppose I raise this issue because I see so much unsuccessful public art that fails in its aim. In contrast to that there is work such as your excellent Shop Local project that you did at PEER Gallery in Hoxton in 2006.[3]

B & R: I suppose one of the excellent aspects of that project is that it’s still actually there. I do think that’s an interesting way to work in that it became somehow functional and occupied the public realm. What made that project effective was that people encountered it without being totally aware. That type of project requires a lot of planning. It seems to me that here in Ireland people seem very keen to engage with ideas whereas in the United Kingdom, the art world seems to be much more driven by the rather insular concerns of the art world.

P: When you were addressing the audience in the art school / drawing room you mentioned the idea of people ‘thinking’ with other parts of their body. I interpreted that as an encouragement for people to try to take a more holistic view of things. The comment make made me think of Rudolf Steiner, who I’ve been interested in for some time, and in particular a comment made by Steiner in which he said: “Just as in the body, eye and ear develop as organs of perception, as senses for bodily processes, so does a man develop in himself soul and spiritual organs of perception through which the soul and spiritual worlds are opened to him. For those who do not have such higher senses, these worlds are dark and silent, just as the bodily world is dark and silent for a being without eyes and ears.” [4] This type of thinking obviously had a great influence upon artists like Joseph Beuys whose work was emphatically pedagogical. I am curious to know if you feel that society, and indeed techno-capitalist society destroys certain innate skills and perceptual abilities by failing to recognise and develop them? The idea that children might be able to use art as a means of becoming powerful seems somehow implicit in this. Perhaps you could discuss whether these thinkers have had any impact upon your work?

B & R: I am extremely interested in figures like Rudolf Steiner and also Johannes Itten. In some ways one can read their work for its humorous qualities because it is so didactic and makes so many claims for itself. I do think that Steiner schools are excellent for many reasons. I’ve always found that when children encounter perplexity or some sort of blankness, they will always find ways of dealing with it in many successful ways. In general most children have no problem addressing visual problems. The idea that art makes children and indeed humans powerful has many repercussions. Those kinds of thinkers are interesting for their interdisciplinary nature and vision, and that is something else that I very much enjoy. In the Kilkenny exhibition for example I worked with a local sign painter whose skill is something often considered outside of the category of fine art. In London at the moment I’m working with a number of choirs to produce a choral piece that will be presented in the autumn at the Royal Festival Hall. In the past I have also worked with Hawkins/Brown architects in London and I must say that I really do enjoy these interdisciplinary relationships.

P: Your work references the idealism of the 1930s. Do you believe that art has become depoliticized? That the cult of celebrity for the sake of itself has dominated? As one who grew up in a time when cynicism and irony dominated, I admire what I see as sincerity in your work.

B & R: I think there is a new phenomenon of artists who want to address politics in a truthful and open sort of way. There are few of them. One of the key people in all that is of course Ai Weiwei. I do think that there are a number of artists who are working at the moment who do take a genuine stance and do have something valuable to express. I think the person who represents this most at the moment is of course Ai. Another recent work I think is important is Mark Wallinger’s State Britain at Tate Britain in 2007.[5] The project that Jeremy Deller developed for the Turner Prize in 2004, which included a copy of the Hutton Report for viewers to read, was excellent. And then there are artists like Cornelia Parker whose work may not be overtly political, but whose interest in environmental issues and stance against certain matters evinces a strong political position. [6] Surprisingly, this can also be said for Anish Kapoor whose work is in many ways apolitical but who is clearly concerned with ethics. He has been quite involved with Amnesty International and when Ai was imprisoned, Kapoor pulled his British Council Show in China. He explicitly made that a political issue, which is deeply admirable. These are just some of the artists that I can think of immediately who are trying to change things with there work. But yes, there are also many artists who avoid this method because they concerned that taking a position might damage their market value. I suppose there is a long tradition here in Ireland of artists being quite involved with political issues—particularly musicians. I know that people do criticise Bob Geldof and Bono, and while sometimes they do frame things in a simplistic way I think that for the most part they are to be admired. Ultimately, I just think it’s important that artists are visible and contributing to the conversation.

[1] This piece was entitled The Oval Court and was included in an exhibition entitled Of Mutability, which took place at the ICA in London in 1986. The Oval Court consisted of many photocopies of the artist’s own body made using a Canon photocopier.

[2] This piece was entitled Carcass and comprised a two-metre high rectangular Perspex column filled with decomposing vegetable matter. This piece was also installed at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1986 as part of Chadwick’s solo exhibition Of Mutability.

[3] This project entailed Bob & Roberta Smith designing and painting one-off advertisements for independent and individual high street businesses. The intention of the project was to counter the visual homogenization, which has resulted from the proliferation of multinational supermarkets, etc.

[4] Rudolf Steiner, Theosophy: An Introduction to the Supersensible Knowledge of the World and the Destination of Man (New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1994), 96. The book was first published in English in 1910.

[5] State Britain was a meticulous recreation of a forty-metre long display, which had originally been, situated around peace campaigner Brian Haw’s protest outside the Houses of Parliament against policies toward Iraq.

[6] In 2008, Cornelia Parker produced a video work in collaboration with Noam Chomsky. It includes an interview in which she asks him his thoughts about “the unfolding environmental disaster now threatening our world.” The piece was presented as part of an exhibition presented in collaboration with Friend of The Earth at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2007.