Institutional Ideators

In the sphere of visual art, the term self-institutionalisation has been in use for some time, and implemented by artists for a constellation of reasons. The mimicry of systems and structures of institutional organisation, for example, may stem from a desire to expose them. Additionally, elevating a particular set of ideas to the status of an institution lends validity to whatever is deemed important to that individual or group. The latter strategy can potentially have the effect of destabilising other, “offcial” institutions that uphold the hegemonic order of society. It is important to note, however, that these aforementioned strategies can also be implemented almost fetishistically, for formal purposes. Indeed, the term self-institutionalisation can be used to refer to all of the above tendencies. But where did this artistic tendency come from, and to what latent desires does it speak?

In Culture and Administration, frst published in 1960, Theodor Adorno argued that, from the Age of Enlightenment onward, society moved rapidly towards what he describes as ‘a totally administered society’ (1). This process, Adorno claimed, was accompanied by the widespread implementation of insidious forms of social control. These hegemonic power structures ultimately occurred in order to fortify the dominant order of industrial capitalism. According to Adorno, the process continued to progress steadily and now permeates every facet of society; ‘whoever speaks of culture speaks of administration as well,’ he writes with characteristic pessimism, ‘whether this is his intention or not’ (2). The years that immediately followed publication of Adorno’s essay saw a proliferation of artists who certainly did speak of administration in their work; namely the constellation of artists that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, who, because of their prioritisation of ideas, information and process, would come to be grouped together under the (generalising) term ‘Conceptual Art’. Benjamin Buchloh assessed their strategies in his 1990 essay ‘Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetics of Administration to the Critique of Institutions’. In an insightful analysis, Buchloh explores how, from the 1960s onwards, artists from a variety of backgrounds and with differing agendas began to adopt and utilise aesthetics and strategies from non-art disciplines, introducing them back into the sphere of visual art. For Buchloh, these artists were engaged in a Duchampian act of appropriation. However, instead of appropriating quotidian objects and transforming them into readymades, artists appropriated bureaucratic and institutional processes and subverted them in the process. Reflecting on the late sixties and seventies, Buchloh argues that this group of artists was unifed by a desire ‘to engage in a complete paradigmatic shift — a deconstruction of the aesthetic structures upon which visual art was built’(3). Crucially, Buchloh claims this desire to overhaul the aesthetic foundations of visual art was for the most part motivated by a spirit of critique, hinged to the seemingly-paradoxical desire to ‘mime the operating logic of late capitalism’(4).

Buchloh’s argument certainly stands when we consider the work of Andrea Fraser (b.1965-), one of the pioneers of second wave institutional critique. From the late 1980s onwards, Fraser’s work has demonstrated how strategies introduced three decades earlier were further developed and radicalised. For Fraser, one of the symptoms of an excessively administered society is the internalisation of administrative and institutional behaviour. Through this process, the intentions of the cultural producer are shaped by the same logic that sustains organisations like “established” museums and galleries. Through a variety of interventions that draw attention to behaviours that are embodied, and performed by people, Fraser’s practice seeks to draw attention to ‘institutional hierarchies and self-interests(5)’ within the art world. The institution is ‘internalized in the competencies, conceptual models, and modes of perception that allow us to produce, write, and understand art, or simply to recognize art as art, whether as artists, critics, curators, art historians, dealers, collectors, or museum visitors’ (6). Essentially, Fraser’s position suggests the totally administered system of contemporary art stems from an internal, institutionalising logic. She writes: We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward, and what kind of rewards we aspire to. Because the institution of art is internalized, embodied, and performed by individuals, these are the questions that institutional critique demands we ask, above all, of ourselves. (7)

While much of Buchloh’s essay is undoubtedly accurate and insightful with regard to institutional critique, it is important to note that other artists were drawn to appropriative strategies for reasons that were not in any way inherently critical. For Buchloh, artists who adopted these tactics did so only as a means of subjecting ‘the last residues of artistic aspiration toward transcendence to the rigorous and relentless order of the vernacular of administration’ (8). But why should what he calls the vernacular of administration be anathema to artistic aspiration? Buchloh’s essay depends on two fallacies regarding these strategies; namely, that they are inherently intended to be critical, and that they are also somehow in opposition to transcendence. Buchloh’s over-estimation of certain motives, however, ensures he neglects some of the other motives behind the tendency towards administrative aesthetics. To be specific, it seems to me that Buchloh’s reading fails to take into account some of the more absurd, poetic, psychological and indeed pleasurable aspects of administrative or bureaucratic procedures. Instead of the aesthetics of administration, perhaps self-institutionalisation is a more rounded, complicated and indeed inclusive term that takes into account the aforementioned aspects.

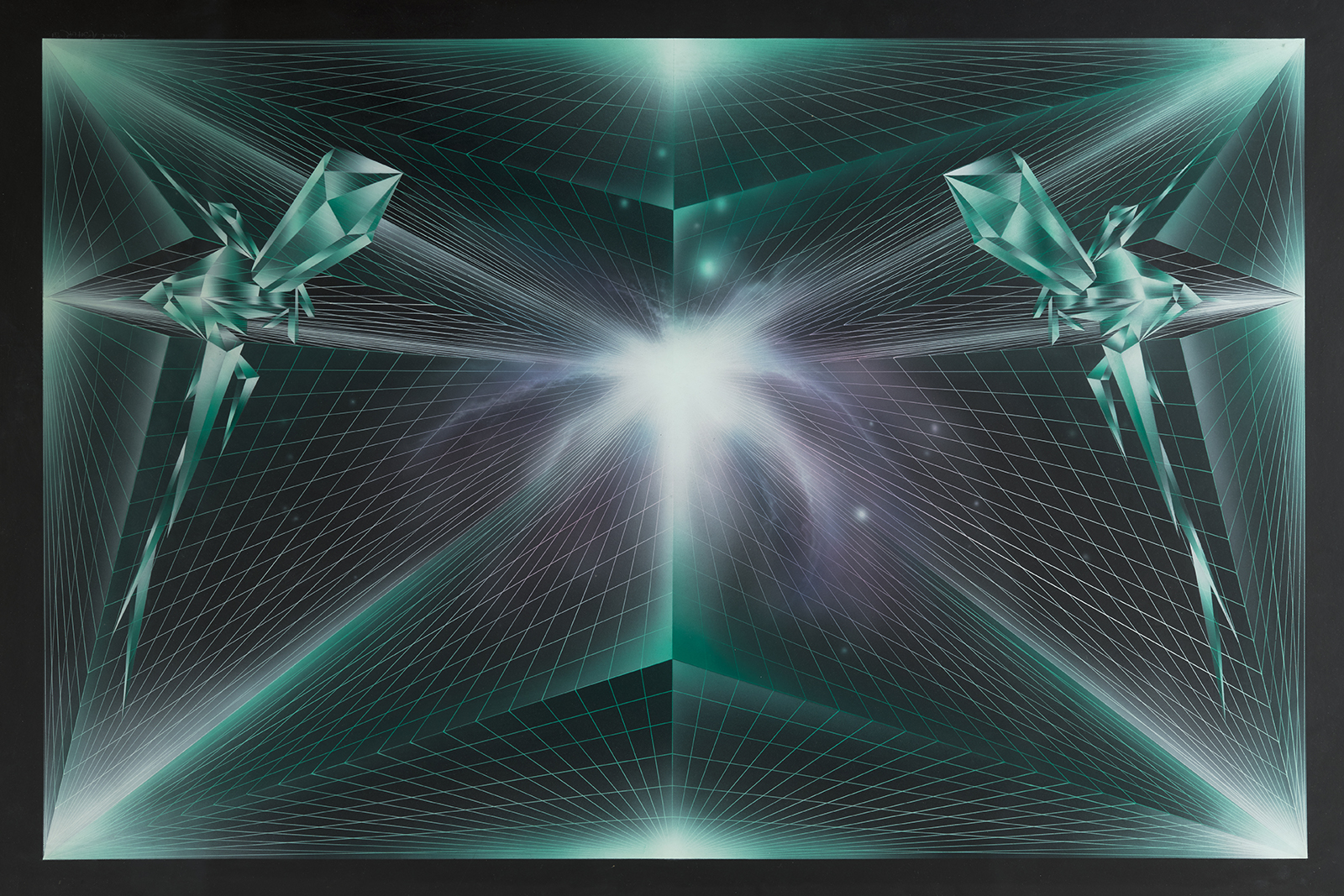

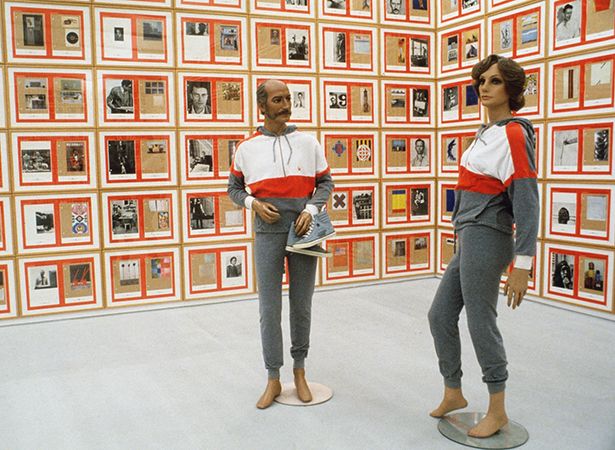

Undoubtedly, Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976) can be seen as a pioneer of what we are calling self-institutionalisation. In 1968, Broodthaers declared himself the director of his own institution, the Department of Eagles. For the next four years, this traveling museum took on several forms, culminating in an exhibition of hundreds of eagle-themed images and fgurines. Broodthaers chose the bird of prey, he said, because it was an emblem of authority, and hierarchical power, qualities he wanted to subvert and expose as inherently unstable. Another pertinent example in thinking about self-institutionalisation is Hanne Darboven (1941-2009). Darboven’s work is distinguished by an administrative, archival approach that utilises numeric systems and idiosyncratic ordering systems, many of her own making. While bureaucratic in aesthetic, however, her oeuvre is fundamentally poetic, presenting the viewer with a very particular idea of the individual who created it. The calendar forms a foundation of Darboven’s art practice and there is an obsessive, devotional aspect to Darboven’s processes; her exhaustive lists and archives, for example, might be seen as attempts to kill or halt time by storing or recording it. This is exemplifed in one of her best-known works, an accumulation of material entitled Kulturgeschichte (Cultural History 1880–1983). The curator and art historian Lynne Cooke’s description offers some insights into the magnitude of this elephantine work: ‘Composed of 1,590 sheets, each measuring ffty by seventy centimetres, and nineteen sculpture-objects, Kulturgeschichte (Cultural History 1880–1983) is one of Darboven’s grandest, most epic works to date. Weaving together cultural, social, and historical references with autobiographical documents, it synthesises the private with the social, and personal history with collective memory. Braided among the vast numbers of postcards, caches of pinups of flm and rock stars, documentary references to the frst and second world wars, geometric diagrams for textile weaving, a heterogeneous sampling of New York doorways and portals, illustrated covers from major news magazines, plus the contents of an exhibition catalogue devoted to postwar European and American art, and a kitsch literary calendar, are extracts from certain of her earlier works, exhibition catalogues from solo shows, and other mementos of previous exhibitions’(9).

In clinical psychology the term institutionalisation refers to the symptoms that develop after spending prolonged periods of time in psychiatric units or places of incarceration. The subject or patient becomes reliant upon the institution, and unable to function outside of it. This idea of incarceration and pathology is raised by Gary Farrelly of the OJAI who, when discussing the notion of self-institutionalisation proposes that in some instances it may function as a kind of coping mechanism comparable to Stockholm syndrome. The suggestion is that, in some cases, these aforementioned tendencies are implemented as a means of dealing with life within a totally administered society. This idea can also be connected to the idea of over-identification that originates in Lacanian psychoanalysis but has also been applied to the sphere of visual art. Slavoj Zizek roughly defines the concept of over-identification as ‘taking the system more seriously than it takes itself seriously’. Essentially, this means adopting, often fanatically, ideas, images, or politics, and not attacking them by a direct, open or straightforward critique, ‘but rather through a rabid and obscenely exaggerated adoption of them’ (10).

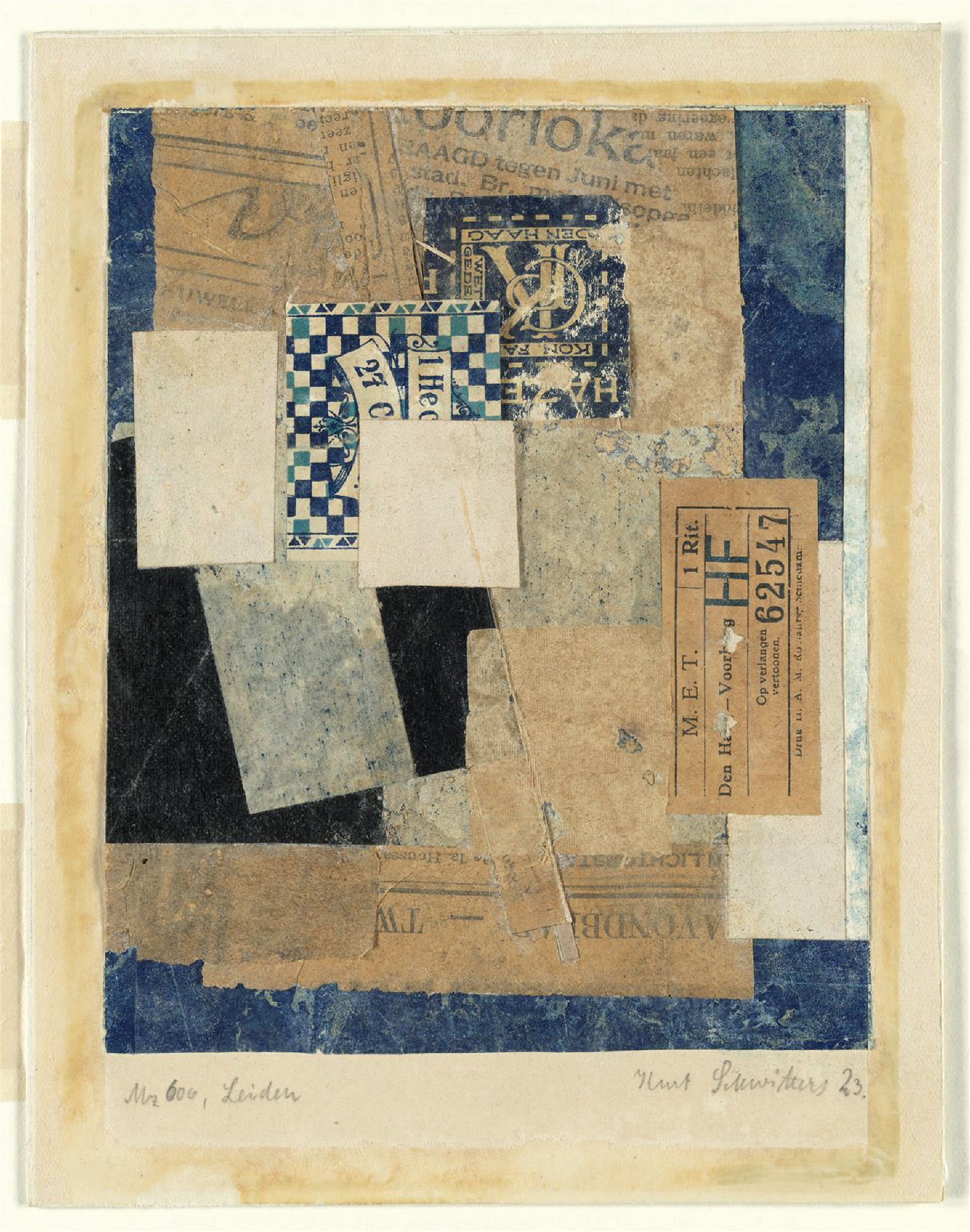

This tactic has been adopted most notably with the NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst), a collective of artists renowned for cultural subversion and sabotage within the ideologically charged context of post-Tito Yugoslavia. More than any of the other examples given here, the work of the NSK could be described as cultural activism. While many of these practices came to prominence from the 1960s onwards, there are also several earlier artists whose work displays similar tendencies. One crucial example is Kurt Schwitters (1887 – 1948), who in 1918 founded the one-man movement, Merz. Between 1918 and 1947 Schwitters produced a series of individually numbered works under the Merz title: packaging labels, train schedules, ticket stubs, envelopes, receipts, and other remnants of officialdom. And, while Merz was essentially a faction of Dada and shares a lot of common ground with it, Schwitters was ultimately concerned with creating order from the detritus of early twentieth-century life. Reflecting in 1930 he stated: ‘Everything had broken down in any case, and new things had to be made out of the fragments’(11). Using mass-produced materials was a shortcut to denote systems of bureaucracy and administrative order. Even the title of his one-man movement – devised by cutting a scrap from the second syllable of the German word “Kommerz” (commerce) – is connected to the emulation of an institution. In this instance, the tendency towards nomenclatures and ordering measures is driven by a desire to organise and self-institutionalise. Schwitters’ decision to number each of the works as an ongoing series, furthermore, demonstrates an early case of branding as art form, foregrounding their participation within the broader logic of capitalist exchange.

Describing any tendencies within the visual arts using broad terms or categories always fails, in that it tends to eliminate details, along with differentiating or contradictory elements. Nonetheless, these descriptions remain useful in describing shared characteristics and patterns that emerge over broader stretches of time. In the three decades since Buchloh’s essay was published, many of the strategies first implemented by artists who came to be affiliated with Conceptualism have been widely adopted. Countless artists continue to embrace the trappings of bureaucracy – among them, paperwork, documentation, work with advertisements and news publications, the issuing and negotiation of contracts, and communication as art form – not necessarily in the spirit of critique but as a specific self-devised methodology. Looking at the various practitioners who utilise self-institutionalisation as an artistic strategy it becomes evident that their work can be divided into two categories. On one hand there are those who emulate, mimic or over-identify with a given institution as a means of critique, as exemplified by the work of NSK and Fraser. In this way, they hope to reveal the systems of hegemony and privilege that sustain these institutions. On the other hand, there are those who generate their own institutions, as a means of elevating and implementing their own idiosyncratic methodologies and interests, which may be gleaned from what have traditionally been viewed as non-art disciplines.12 Many practices sit somewhere in between these tendencies but all serve to underscore the ongoing potential of strategies founded on self-institutionalisation.

Thus far we have considered twentieth century artists, whose work can be viewed retrospectively as constituting self-institutional practices. All of these examples evince that, while self-institutionalisation may have numerous motivations and take multiple forms, it always betrays a desire to explore systems of control. As we enter into the second decade of the twenty-first century, the possibilities of self-institutionalisation, what it is and what it offers us, are evolving too. In this era, media culture bombards us with endless stimulation, distraction and opportunities for communication, creating a form of social control via a diffuse, technological system of forced participation. The upshot of this is the prevalence of a subtle, insidious form of techno-rational containment. Crucially, this form of control encounters less resistance than the domineering top-down hegemonies of previous decades.13 In the sphere of culture, perhaps strategies of self-institutionalisation can offer us viable possibilities for resistance. We have two choices: we can either entirely embrace the status quo and be part of helping it progress towards its most severe, dystopian conclusions, or we can devise and abide by our own equivalent ‘institutions,’ built upon a desire to realise liberation, autonomy and self-actualisation.

- This idea was also explored by Michel Foucault who argued that while institutions may profess a certain neutrality they are inherently structured to maintain a particular set of power structures.

- Theodor W. Adorno. The Culture Industry. Selected essays on mass culture. Edited by J. M. Bernstein. (London, Routledge, 1991) p.107.

- Benjamin H. D. Buchloh ‘Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions’. October Vol. 55 (Winter, 1990), pp. 105-143. 4. Ibid.

- Andrea Fraser, From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique. Artforum. Vol. 44, Issue 1 (Sept. 2005), pp. 100-107

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Buchloh, ibid

- Lynne Cooke and Michael Govan. Dia, The Collection in Beacon (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2003) p. 118

- Stevphen Shukaitis. ‘Overidentification and/or bust?’ Variant no. 37 (2010), pp. 26-29, available at: http://www.variant.org.uk/37_38texts/10Overident.html

- Translation in Schmalenbach, Kurt Schwitters (1967), p. 35

- The OJAI exemplify how the latter is often accompanied by a tendency toward self-publishing and self-initiated research.

- These ideas are also addressed by Diedrich Diederichsen in his essay “Entertainment through Pain” featured in Maria Fusco / Richard Birkett (eds.): Cosey Complex . London: Koenig Books, 2012.