Psychedelic Suburban Esotericism

I

The Lords and the New Creatures

The work of Richard Proffitt is replete with the fragments of late 20th century countercultures. However, references to subcultural strands that emerged in the 1960s are particularly prevalent. One might view Proffitt’s installations as evidence of the assertion made by Jon Savage that ‘society is still dominated by a brief but explosive period in the mid-sixties whose implications (and detritus) live with us still’. The components of Proffitt’s installations and the manner in which they are arranged always suggest an underlying narrative. For several reasons this narrative is one that I’m compelled to insert myself -or to be more accurate- my teenage self into. For although the teen faction of which I was part of in the mid 90s was extremely heterogeneous and couldn’t be neatly categorised as any one subculture we all subscribed to a kind of neo-hippy eclecticism. In addition to our unruly behaviour, arrogant idealism and proclivity for hedonistic pursuits what united us was a penchant for fetishising certain musical genres and stylistic traits from buried decades. In 1996 I began carrying a book of Jim Morrison’s collected poems titled The Lords and the New Creatures around everywhere in the pocket of my leather jacket. Although I look back upon this as a pretentious affectation I can also still recall how the book really did hold a talismanic quality at the time. It was as though the book represented some sort of authenticity that was unavailable anywhere. I would read it when I was alone, projecting myself into the dense psychedelic imagery as a means of devotion. When with friends I would read the poems out loud, performing them like invocations. The fact that the cultural artefacts with which we were obsessed were decades old didn’t lessen our engagement in any way. The vintage of such material -and the knowledge that it had ‘turned on’ generations previously only augmented its potency. Although unremembered, the culture to which we subscribed seemed imbued with a mystical potency we believed was unavailable in the era in which we lived. These collective expressions were the first time I ever grasped any notion of what it meant to transcend the quotidian via devotion to something ‘sacred’. Moreover, our reverence and celebration seemed to satisfy a need to connect while also enabling us to feel somehow different, as though we were associating with notions of ‘otherness’.

II

A focus for inter-subjectivity amongst individuals

Proffitt’s installations are typically comprised of complex accumulations of detritus sprawled across gallery floors and assemblages made from a multitude of materials propped against or hanging from walls. Although Proffitt often reuses components in his work they are always reconfigured in different ways according to the context in which they are displayed. In these installations a profusion of elements is assembled in a manner in which the visual impact is secondary to the ritual function. One might encounter a makeshift altar made from baroque chunks of driftwood, glass bottles containing incense sticks and a sheep skull illuminated with a yellow light bulb to form the centrepiece. From the walls one might see hanging dream catchers which the artist has made from threads and seashells or mandalas made from mirror shards glued to a moon of black lacquered cardboard. This use of what one might call ‘low’ materials is a key strategy in Proffitt’s work. For although Proffitt uses debris and mass-produced ephemera that has been rejected because its use value has expired there can be no doubt about the magical potential of the objects he makes. Proffitt’s use of flotsam and jetsam is a demonstration of the way in which any object can become a focus for inter –subjectivity amongst individuals. Moreover, Proffitt’s use of junk to create shrines and sacramental spaces is a demonstration of the fact that with sufficient imagination/will power any object can become a totem; imbued with ritualistic potency and usable as a device or conduit for summoning an invisible agency or subtle energy.

III

Memory of the fetish object

Non-Western art forms provided a major catalyst for development for the early 20th century avant-garde. Artists who sought to develop new visual vocabularies looked to the artefacts which they mainly encountered in ethnographic museums. The aesthetic qualities of these artefacts and the fact that they were seen as ‘authentic’ or ‘primitive’ expressions resonated with many of those artists now considered as seminal modernists. While initially it was the visual properties that attracted artists to these objects their conceptual potential caught the imaginations of artists as the 20th century progressed. Artists of the Surrealist movement were particularly interest in ethnographic art. This interest was particularly evident in the work of Surrealist Kurt Seligman who researched the fields of comparative mythology and religion and contributed to the emergence of a global view of magic without western bias. What interested Surrealists like Seligman most was the notion that ethnographic art objects could be imbued with numinous properties on account of the sacramental function that they originally had. These concepts were also explored in depth by Walter Benjamin, a contemporary of the Surrealists who in his seminal 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction ponders the ritualistic origins of all art forms. According to Benjamin, the contemporary art object still a genetic memory of its original function as a fetish object, used by ‘primitive’ man produced as tools in acts of sorcery. Essentially, Benjamin proposed that the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual. In Richard Proffitt’s work the magical potential of the art object is no longer just a memory- the original function of the work (according to Benjamin) is restored and the artwork becomes a magical device for a secular age. Those objects which Proffitt has produced from mainly organic components; feathers, shells, wood and textiles, are not at all dissimilar to those which one might view on display in an ethnographic museum. They possess a distinctly liturgical appearance and one can easily imagine them being used as devices conceived to invoke spiritual responses.

IV

Psychedelic suburban esotericism

My first significant encounter with the work of Richard Proffitt occurred in Dublin in 2013 when I attended his solo exhibition entitled Eternal Spirit Canyon. The exhibition was immersive and comprised of a sprawl of components arranged throughout the gallery space into a narrative scene. Eschewing symmetry and a countenance of completion, this congregation of objects extending beyond peripheral vision and the meanderings of this grouping precluded the possibility of a single central focus. A red light bulb illuminated ludic arrangements of objects; a; knotted assemblage of bones, rope and fabric hung from the wall. A battered portable CD player emitted a hypnotic mantra that I recognised as an excerpt from an early Pink Floyd tune. The various components of the installation and the overall atmosphere immediately evoked the haunts of my own teenage years which -like Proffitt’s installations- reflect a sensibility and social aesthetic practice that can best be described as psychedelic suburban esotericism. In those spaces -which I spent so much time as a teen-style, music and selfidentity interconnected. They were personalised with posters, photos, books, CD’s, cassettes, records, musical instruments, artworks, amplification devices and other forms of miscellaneous paraphernalia, which seemed appropriate in creating ‘atmosphere’. Located in attics, basements, garden sheds, garages but more often than not bedrooms these territories which my friends and I spent our time functioned as sanctuaries from a world that seemed increasingly adversarial. These personalised spaces were havens from the authority one inevitably encounters -and often struggles with- during adolescence. It was in these territories where transgressions could be made and where formative – perhaps even seminal- experiences took place for the first time.

V

Sense of identity could be crystallised and communicated

Encounters with the work of Proffitt are one of several factors that prompted me in recent years to reflect upon these domestic haunts my friends and I spent much of our teenage years in. Another factor that contributed to me reconsidering these zones in a new light was my reading of psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s essay struggling through the doldrums. The essay was first published in the early 1960s when the concept of the teenager as we understand it today was still taking shape. In this essay Winnicott defends the importance of adolescence, stating that it is a vital phase in one’s development which society needs to accommodate. According to Winnicott “society needs to include the doldrums as a permanent feature and to tolerate it, react actively to it, in fact to come to meet it but not ‘cure’ it”. Analysing behaviour now seen as typical amongst teens Winnicott attempts to identify the roots and causes of certain conventions. According to Winnicott, the tendency towards gathering objects and possessions around oneself has its origins in infancy when one develops attachments to comfort objects such as teddy bears, security blankets etc. Winnicott claims that this behaviour -which is initially the manifestation of a need for some sense of security- continues throughout one’s life, allowing one to negotiate the relationship between their ‘inner’ emotional reality and the outer world. In one’s teens the process of gathering and surrounding oneself in paraphernalia that reflects one’s personal tastes enables one to develop social bonds and a sense of self in relationship to the rest of society. Moreover, on a psychological level this behaviour enables one to gain some sense of control during a difficult phase of ‘internal reassessment’. Winnicott argues that the process of developing one’s taste in popular culture and surrounding oneself in the materials associated with can be an inherently creative form of transitional behaviour stemming from that same drive which in later life may manifests through one’s engagement in cultural production. Ultimately, the suggestion is that in addition to being a manifestation of a desire for collective identity these subcultural socially cohesive spaces that teenagers create also enable one to begin constructing one’s ‘own’ sense of culture. My encounters with Proffitt’s installations – which transport me back to my former self-combined with my recent reading of Winnicott made me realise that the spaces my friends and I accumulated and occupied as teenagers were not merely havens for bonding in a world that felt increasingly authoritarian, nor were they merely zones where one could engage in illicit practices. Ultimately, these subcultural spaces were where one’s nascent sense of identity could be crystallised and communicated.

VI

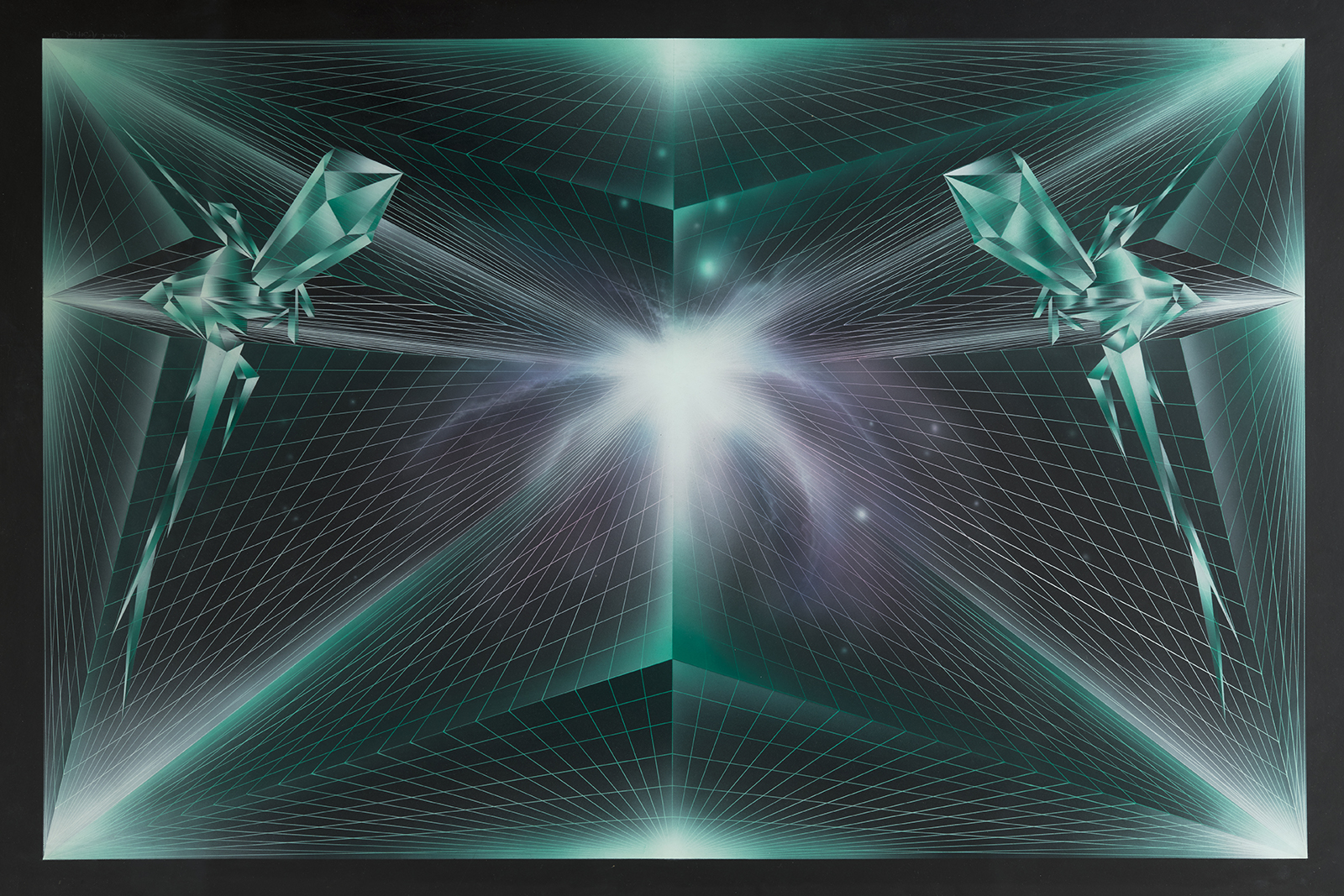

Psychic recollection of artist as shamanistic figure

Richard Proffitt’s work is representative of the major resurgence of interest amongst contemporary artists in visionary experiences, sympathetic magic and the occult. One might situate Proffitt’s work as part of the same tradition as Austin Osman Spare or Joseph Beuys in which a crossover between the roles of cultural producer and shaman is central. However, an aspect of Proffitt’s work that distinguishes it from many other contemporary practitioners is the fact that he doesn’t merely allude to magical practices or symbolism. Over time, I have come to realise that Proffitt’s totemic objects really do hold some magical potential and are integral to an idiosyncratic syncretic system that he observes. Ultimately Proffitt’s approach is a testament to the fact that while the role of the artist within society has changed radically, a psychic recollection of artist as shamanistic figure is retained.