Home

In his often quoted 1934 lecture “Author as Producer”, Walter Benjamin stated “the rigid, isolated object is of no use whatsoever. It must be inserted into the context of living social relation”s (1). Though literary and critical production was Benjamin’s primary concern, this statement -which I’ve been compelled to quote elsewhere- is equally applicable to the realm of visual art. Rather than awkwardly insert or impose paintings or prints into social situations, Brian Maguire takes such situations as his point of departure. The corollary of this approach is that the individuals and situations the artist encounters, dictate and influence the emergence of an artwork or group of artworks. A tendency to plant himself within challenging situations, in his devotion to giving form to that which is often obscured and excluded, is a key aspect of Maguire’s approach; knowledge of which, I believe, is key to understanding his work. The artist’s use of interactive strategies is never exploitative but sensitive to the situation and sufficiently flexible to allow for chance encounters and occurrences. Fostering a discursive practice, in which the material trajectory of a project is shaped and focused by social interaction with different individuals, is one way Maguire prevents his work from becoming neutralised or formulaic. In this way the artist continues to produce work that is as engaging and challenging as anything which he produced before occupying a prominent position on the topography of Irish art.

As the most tangible trajectory of Maguire’s approach shows, he is first and foremost a painter. Yet speaking with the artist one becomes aware that, for him, painting is just one element of a multi-faceted process, in which a preoccupation with aesthetic and stylistic matters is balanced by an awareness of political and social issues . This is, without a doubt, connected to the fact that Maguire’s convictions, which have strengthened over time, stem from a determination to utilise art as a means of inciting change in the socio-political sphere (2). Maguire’s practice revives the possibilities inherent in the medium of paint by utilising and adapting it as a tool and trigger for exploration of issues and individuals that are usually situated outside the comfortable sphere of visual art. There is a danger that such an approach could be seen as patronising, but Maguire consistently sidesteps a moralising tone.

During the course of a conversation with Maguire, he describes how his paintings emerge from a series of what he refers to as “actions”. In this context Maguire’s use of this word refers to episodes of concentrated activity, akin to a private physical performance before the canvas, punctuated by lengthy periods of research, dialogue and contemplation. Though obviously very different, I cannot but connect Maguire’s use of the term “actions” with that definition proposed by Wassily Kandinsky, who suggested that the ‘actions’ of the artist are what create the ‘spiritual atmosphere’ of a society. While the process of painting pictures might involve such sequences of actions, the paintings themselves are ultimately an index or ‘by product’ of other activities which occur beyond the studio and are capable of eschewing passivity-both within himself and potentially the viewer.

This is exemplified by the fact that the starting point for this new body of prints and paintings was a process of dialogue with individuals who, over the course of the past 5 years, relocated to the town of Blessington Co.Wicklow from elsewhere in Ireland, as well as from Asia, Africa and Europe. While the underlying use of dialogue unifies this particular endeavour with previous projects, the works are themselves visually distinctive, constituting a significant shift from earlier work.

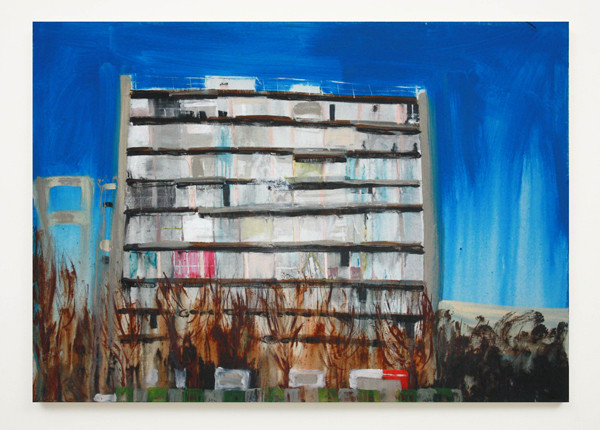

One of the most notable aspects distinguishing these works is that they are comprised almost entirely of architectural landscapes and panoramic vistas, all of which are devoid of human presence. Though a glance across Maguire’s oeuvre reveals notable examples of artworks in which architecture and landscape are a focus, it is more typical to see these integrated into a composition, as a means of heightening intensity or creating a certain atmosphere. Only rarely would these have been the sole focus of an entire painting. What also differentiates these works is the absence of any explicitly politicised iconography and the development of a daring turn toward operating with what might be considered conventional modes of painted beauty. This gives rise to important contradictions, that are themselves pregnant with meaning. Furthermore, the expansive scale of some of these works, combined with the fact that there is a seeming emptiness that allows one to be engulfed, characterises these scenes. There are no other figures with which to identify and so we can project ourselves into these scenes without hesitation.

These diverse images are all sufficiently tractable to accommodate the personal readings and reflections of a viewer and there is a vacancy within the larger pieces in this group, which encourages one to enter the image and become something of a participant. The paintings are each rooted in the specifics of the various locations they touch upon- Ireland, Belgium, Cameroon, Japan and Poland. The land and cityscapes are given form via the artist’s unique sense of visual character and in several instances assume a directly symbolic function, which still accomodates one’s own subjective response. This is apparent in the juxataposition of those works placed in dialectic couplets, in which new connotations and open ended meanings are brought to bear. While reading these works together as a group of scenes, might lead one to assume that the artist is addressing issues of place and identity, they also inadvertently reveal how today, our changing perceptions of time and space have eroded distinctions separating the local from the global.

Much has been written over the years of the dark or “depressive” nature of Brian Maguire’s work. In a text written late in the last century, Donald Kuspit focused on the violent qualities of the work in such depth that other qualities seemed neglected (3). Obviously for the sake of clarity and focused argument, Kuspit chooses to focus upon specific qualities in Maguire’s paintings. The tendency of critics to focus upon the proliferation of violent or dark imagery is perhaps hardly surprising, considering that the work Maguire was producing at the time was undoubtedly distinguished by such imagery. However, it would seem that Maguire is increasingly willing to surrender to the desire to give pleasure to the viewer and this is exemplified more clearly in these new works than ever before. The artist explains that he always sets out to make a thing of beauty -even though it may also contain threatening and foreboding aspects – for ultimately “beauty is what lures the viewer in (4) ”. However, while there is (with the exception of “Trauma centre”) ostensibly no sense of shock-factor to these works (in comparison with earlier work where brutal subject matter would slowly emerge from seductive hues) the aforementioned absence of any protagonists in these works makes the images all the more powerful -especially to one familiar with Maguire’s previous work.

Each zone is loaded with a complex web of narratives, almost all concerned in some way with man’s capacity to retain dignity and strength in extreme adversity .Learning that Maguire had a guide in each location that he painted, with whom he spent time and developed a friendship of sorts, emphasises once again that these works are crystallised processes. In one painting an enclosed empty space at the back of tenement blocks is illuminated by ambient twilight. This shadowy sunless space could be a place where children play but it is also a ruin at the edge of the Warsaw ghetto. Though there seems to be no human presence within this space, it is clearly a site where the echoes of the past continue to reverberate. In another painting we see a conurbation in the suburbs of West Dublin. Car headlights point toward this distant development, set out and cut off amongst the fields. Pools of light illuminate the grassy foreground. Looking at this painting, in which the silhouette of a housing estate is set beneath a vast expanse of turbulent sky, it seems that there is a process of conversion occurring in the work. Anonymous hinterlands and half familiar structures become charged.Of all these paintings the image which is perhaps the least ambiguous, in terms of atmosphere, is that, of an interior of a stairwell in a government building somewhere in Dwali, Cameroon. Despite the intensity of the African sun, the space is cast in gloom and just barely illuminated by rays which penetrate through grills in the walls.

Talking to the artist, it becomes apparent that, in almost every case, these sites were selected because they mark a place where Maguire was himself moved by a particular encounter or even just by a tangible sense of atmosphere; perhaps the residue of some tragic event or ongoing and unresolved problem. Though some of the paintings depict sites where tragedies or atrocities have occurred, others are locations where the artist experienced something uplifting, warming, humbling and ultimately strengthening. In relation to the Tokyo painting, Maguire speaks of the fundamental differences he observed between Japanese and Irish lifestyles in particular the sense of respect and admiration directed toward the elderly of Japan. His encounters with a certain elderly individual in that country made him radically reevaluate his perspective on his own inevitable senility.

While a knowledge of the specific locations depicted in these works might enhance a viewer’s interaction to some degree, the true value of these works lies in the fact that, as a group, they are concerned with the universality of the human condition. Ultimately this body of work is concerned with the universality and also the commonality of experience. In meeting with and allowing himself be guided around these locations by native inhabitants, Maguire became an acquiescent follower and submitted to the kindness of his guides. In this way the paintings emerge from direct communication founded upon Maguire surrendering control to others and there is a trace of that in the works. Each area of colour, contoured only by the physical edges of the paint, is applied expansively and flat surfaces of the canvas become the landscape upon which conflict and resolution take place. The artist’s distinctive physical technique in applying paint to the canvas underscores the status of these paintings, as quiet, hand made monuments, to individuals who will not and cannot be known. The directness and deceptive, disarming simplicity with which the images are constructed, makes one eager to keep looking, as though somehow we might absorb the essence of these individuals.

There are many layers of meaning to these works, but this is honest painting in so far as the paintings speak for themselves without necessity for recourse to historical and/or anecdotal information.This is consistent with Maguire’s ideal, that his work will reach out to those who might not enter into the hallowed museum or gallery. It is appropriate that prints of these paintings are installed in local authority buildings throughout Wicklow, since they emerge from a process of dialogue with the public but are also ultimately conceived as a means of enhancing the lives of and giving pleasure to that public. As Kuspit like many others have pointed out, the connections between Maguire’s work and that of the German Expressionists are tangible. Their work was also defined by a necessity to marry a sense of practical value with aesthetic pleasure, as though the latter relies upon the former in order to be tolerable. However, what fundamentally differentiates Maguire from many of his 20th century antecedents is that Maguire’s artistic process is not simply confined to the production of paintings but is concerned with using artistic process as a tool in negotiating and implementing real world changes by working with and for the marginalised and the disenfranchised.

(1) Walter Benjamin.The Author as Producer. Art in Theory 1900-2000. Ed.Harrison & Wood. Blackwell UK 2003.

(2) Maguire’s capacity to use landscape as a means to explore ideas concerning violence, power and human depravity is evident in a painting dating from 1996 entitled “lrish landscape”. Three quarters of the painting is occupied by a cross section view of an automatic rifle buried beneath green fields receding back into the horizon, which is suggested by a blue streak.

(3) Conversation with the artist. Spring 2009.