Menschheit

Though it is now commonplace to consider the societal conventions demarcating differences between masculine and feminine as autonomous from corporeal sex as assigned at birth, assumptions concerning gender roles remain steadfastly in situ, perpetuated through social interstices, cultural norms and advertising propaganda. Within the context of cultural production, the sex of an author continues to dictate how his/her work is interpreted, as well as if and where they are immortalised within the narratives of art history. Moreover, many of the gender connotations attached to or accrued by certain artforms in the past remain firmly intact, lending credence to the fallacy that particular artforms or artistic approaches are innately male or female.

Writing about the complexities of sexual difference and the related but doubly perplexing question of its relationship to visual art is a hazardous affair, for language is a slippery material and using it to explore such a contentious and ambiguous issue is to risk unwittingly corroborating cultural or ideological prepotency. As one who approaches the problematic issue of gender – and its relationship to visual art – with trepidation, I was struck by the text accompanying ‘Menschheit’, in which the forthright assertion was made that this exhibition was a ‘thing of men’. On first glance it seemed an endorsement of reductive stereotypes to describe an exhibition – in which the work featured appeared initially to be unified by a curt hardness, brusque rigidity, slick, neat orderliness and propensity toward verticals – as a ‘thing of men’. However, on viewing the show it became apparent that in this instance the act of designating a diverse body of work as male was not to suggest there could be an indexical visual definition of maleness.This was in fact a self-reflexive gesture intended to encourage a process of deconstruction and a reappraisal of definitions of masculinity and femininity as binary opposites. Viewed carefully, with time and through the lens of gender – as the authorial frame of the exhibition intended – it became apparent that while the works in this exhibition possessed properties corresponding to clichéd notions of masculinity, they also contained qualities that could be interpreted as contrasting with prevalent constructions of maleness.

The co-existence of the aforementioned characteristics (which some might view as signifying masculinity) alongside properties evoking uncertainty, instability, weakness and vulnerability were evident in Brendan Earley’s Monument. Though initially resembling a generational descendent of the primary objects of David Smith or Sol LeWitt, Earley’s stacked structure was distinguished by a twisted posture that conveyed a sense of precariousness. Unlike the forms of Smith and LeWitt, which usually exude an erect and stable permanence, this stack looked askew, as if ready to topple at any moment. Though the construction pallets from which the piece was built might have evoked connotations of physical labour, progress and architecture, each was cosmetically concealed beneath uniformally hard and homogenous plasterboard veneers. Beneath this superficial surface were damaged, flawed and worn found objects, which, having fulfilled their function, became rejected cast-offs. In the context of this show, the semiotics of these combined materials were suggestive of a deceptive masquerade in which the surface reveals nothing of the chaotic weakness within. Moreover, the central positioning of this edifice – which might be read as a memorial as much as a monument – was itself significant, for its aura transmitted a tone of insecurity radially upon each of the surrounding artworks.

A similar precariousness was evident in André Niebur’s Untitled, comprising six sticks propped nonchalantly against the gallery wall. Though certainly there was a sophistication to the considered palette that tipped the sticks, each also resembled what one might use to stir paint with. There was a suggestion that these articles were implements used previously in the production of another artwork (now nowhere to be seen). In addition to their vulnerable proneness, the particoloured sticks possessed a sagittal, dart-like quality which inevitably alluded to magic, power-bearing wands and ultimately the rods of office held by church dodsmen; the sceptre of the monarch; the crozier of the bishop; or the conductor’s baton through which an orchestra is controlled.These totemic unbundled fasces could not be viewed without acknowledging their inherent phallic symbolism, problematised and undermined by their vulnerability to collapse.

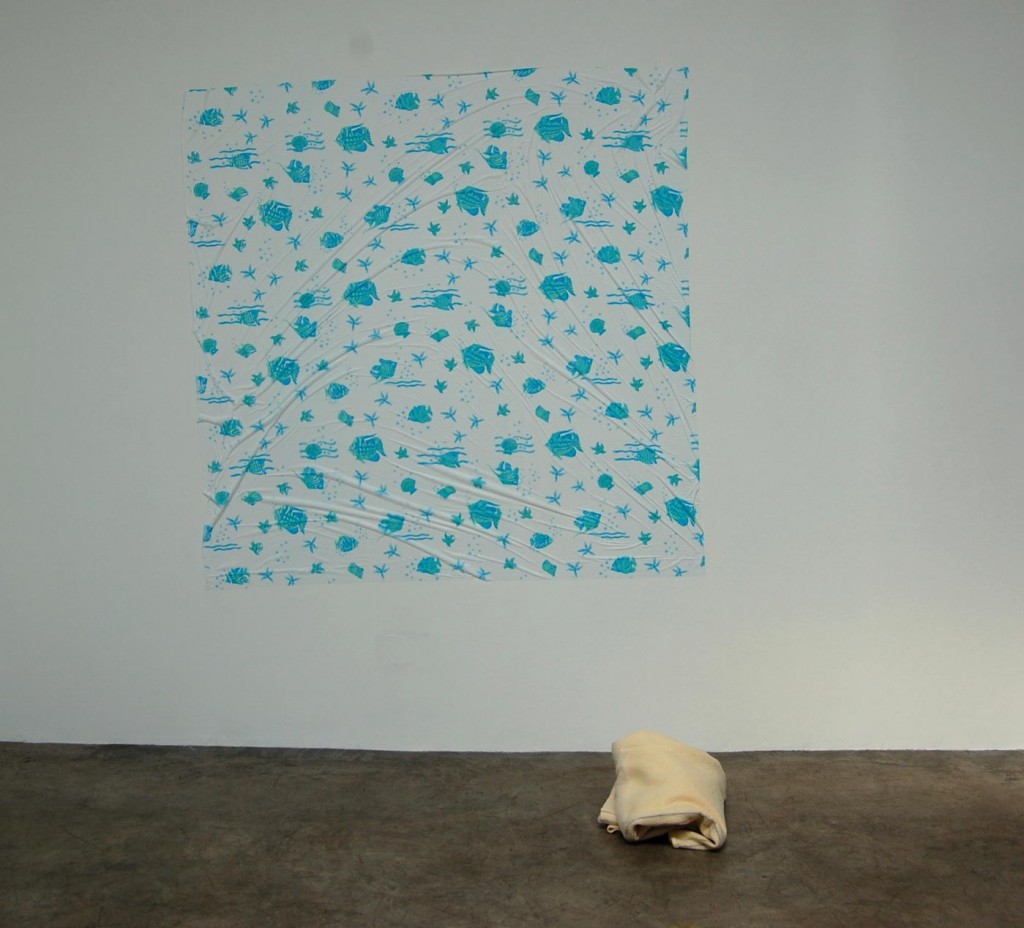

Implications of tense instability and imminent fall were equally present in Simon Denny’s Untitled (Blue Fish), when one realised that the synthetic tablecloth upon which its blue marine motif was printed was pinioned to the wall by nothing but static electricity, requiring sporadic recharging from a blanket balled up on the floor. Even viewed outside the thematics of this exhibition, the two domestic components constituting this piece were automatically loaded with gender connotations, underscoring the fact that from early childhood one is conditioned to be acutely aware of what objects and actions are ‘appropriate’ to one’s biological sex. The security blanket was apposite in this context for it may be seen as the first in a succession of objects fetishised as a source of existential comfort and gender-identity construction.

A notion of objects and possessions being central to the construction, definition and substantiation of sexual difference and status was equally relevant to Kevin Cosgrove’s Workshop with Bikes, an elegantly direct painting of an overlit garage, deserted save for the motorcycles and the equipment required for their maintenance. While the motorbike has consistently been presented as a quintessential icon of heterosexual masculinity (as in Laslo Benedek’s 1954 film The Wild One)1 it has accrued additional connotations over the years and is now equally a symbol of homo-masculinity. The motorbike as symbol of alternative masculinity is present in the work of artists such as Kenneth Anger – whose film Scorpio Rising (1964) features the homoerotic antics of leather-clad bikers – and the images of Tom of Finland (1920–1991) in which the bike is transformed into the chrome and steel love-throne of beefcake police officers and leather men. Cosgrove’s work and the iconography it represents therefore inadvertently constitutes a corroboration of the notion that the connotations conveyed by the language of objects are prone not only to slippage, but also to subversion and sabotage – never more than when gender is involved. While evoking traditional, stereotypical notions of masculinity, of fastidious and noble labour, of mechanical repair, the painting equally underscored how seemingly archetypal symbols of gender may be disrupted and corrupted.

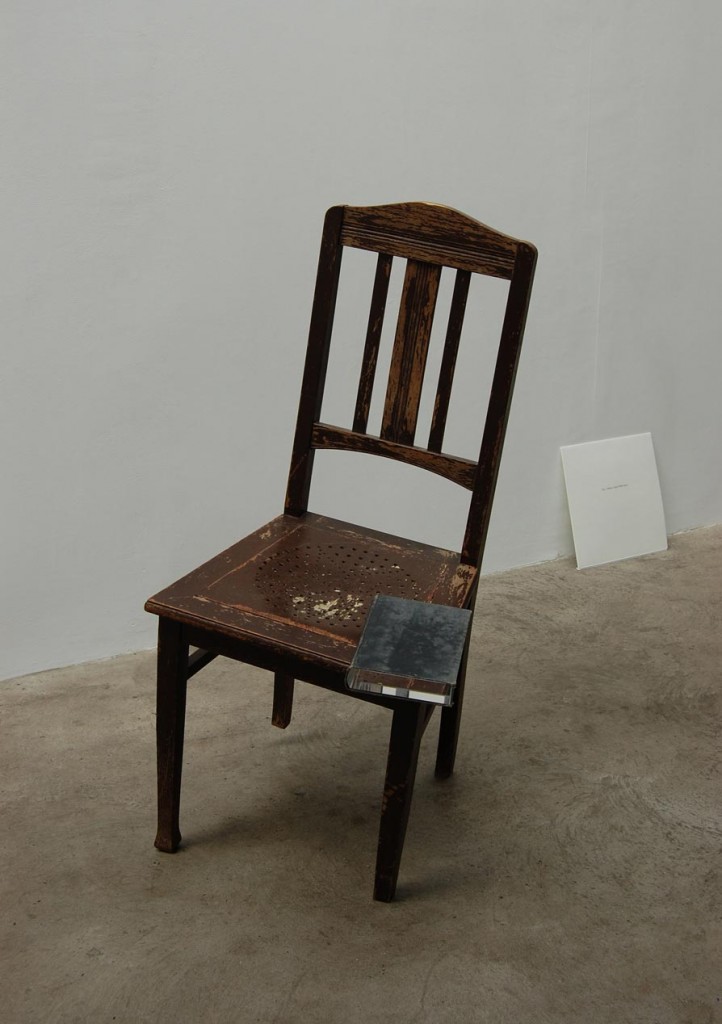

Traditional paragons of mettlesome masculinity were also referenced to some degree in Robin Watkins and Torben Tilly’s On Seeing Through Obstacles, Across Space and Round Corners. This work – which constituted an exhibition in its own right – comprised an idiosyncratic aggregation of objects, positioned in a linear sequence from which any number of narratives could be constructed. The final component in the cryptic procession – and the one that constituted a key or anchor guiding how one might interpret the collage of objects – was a spectacular colour-saturated image from a National Geographic magazine, depicting a gondola belonging to one Colonel Joseph Kittinger (2) (who was inside), suspended in the stratosphere from a silver helium balloon.Though Kittinger’s numerous missions and manoeuvres undoubtedly required great courage, stamina and skill, this image emphasised the diminutive puniness and absolute vulnerability of humankind in the unexplored unknown. Next to this image documenting a moment of ‘world history’ a monitor showed looped footage of latter-day man making repetitive high-velocity percussive actions on a drum kit. The juxtaposition of these two components alone was loaded with meaning, for in our post-post-modern milieu we have arrived at an impasse in which notions of progress, improvement – even movement itself – have been tainted by negative overtones, the corollary being that we are lodged in a state of aggressive and repetitive, anomic stasis.(3)

The potential readings of this work, with its reference to Colonel Kittinger, were almost limitless, but in the context of this show Tilly and Watkin’s work pointed to the fact that the majority of exploratory investigations carried out in the name of progress, manifested through manoeuvres and military procedures, are usually undertaken by those seeking to increase their levels of control and power. Somewhat similar ideas were brought to bear in Ciaran Walsh’s Station – which constituted a fitting parallel in terms of highlighting how modern science might equally be considered as distinguished by what some might consider a particularly male penchant for controlling, exploiting and manipulating the natural world. Station constituted an elaborate assemblage of materials which combined to create a utilitarian-looking device, the actual purpose of which was difficult to discern. Though, ultimately, the design of the structure was Walsh’s own, the materials and indeed the manner in which they were assembled were influenced directly by the research of Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) who, having established himself as a renowned psychiatrist, went on to become the father of what he called Orgone Energy – which he conceived of as a life-force flowing through all things – and the ‘science’ of orgonomy. Reich developed a device named the Orgone Accumulator, believing that the box could be used to accumulate orgone energy which could then be applied to groundbreaking effect in fields as diverse as psychiatry, medicine, biology and weather research. Ultimately, Reich’s investigations led to his discrediting, but while most of his research into orgone energy has been rather vehemently dismissed as pseudo-science,Walsh’s reference exemplifies the tendency within contemporary art toward revisiting arcane concepts and knowledge that have been discounted by and relegated from mainstream practice. Though certainly influenced and informed directly by the work of Reich, Station possessed a distinctively jerry-built aesthetic and, even without an awareness of Reich’s endeavours and problematic legacy, the formal aspects of this work educed stereotypes of obsessive anoraks holed up in garden sheds partaking in pseudo-scientific experiments with potentially nefarious intentions.

According to Pierre Bourdieu’s Masculine Domination, male privilege is a trap and it has its negative side in the permanent tension and contention ‘imposed on every man by the duty to assert his manliness in all circumstances’ (4). Though this exhibition highlighted the fluidity of contemporary definitions of masculinity, there was also something in the selected works that evoked ideas of inadequacy and failure – a kind of insecurity calling to mind Bourdieu’s words in which, while acknowledging the prevalence of the patriarchal order, he states that in order to wield and impose the power afforded by this order men have to partake in a process of self-regulation and submission. This ‘effort that every man has to make to rise to his own childhood conception of manhood’5 involves the careful concealment of his weaknesses in order that he become the generic ‘self’. While much necessary thought, energy and academic research have to date been invested in the recent past in rectifying the silencing of the other (in this case the female), there has been something of a failure to acknowledge that men too are, in the words of Karl Marx, equally dominated by their ‘domination’.

In a seminal 1975 essay,‘Sorties’, Hélène Cixous made a similar statement. She claimed that the inclination to consider gender in terms of binaries was itself a symptom and a device of the patriarchal value system in which sexual difference was understood by coupling it to the idea of opposition.Though not the first to conceive of the distinction between male and female as the root of oppositional binary thinking, Cixous actively critiqued the ethos that she sought to overcome. In her analyses of culture Cixous claimed that centuries of representation and reflection in literature, philosophy and criticism perpetuated oppressive and propounded poetic examples of polarised couplets, in which the female component is positioned as negative: active/passive, culture/nature, head/heart, coloniser/colonised, speaking/writing, day/night, father/mother, head/heart, etc.

Though the focus of Cixous’ attack was the patriarchal paradigm, she acknowledged that men also suffer under this order, because they are also oppressed and restricted by the expectations and assumptions of what their role should be. Like so many of her antecedents, Cixous encouraged the cultivation of an ‘androgynous mind’ in order to transcend the problems of sexual bias. Perhaps there is a fundamental necessity to pursue this goal and dispose with the dialectical relation between the sexes. Perhaps as long as this difference exists, the experience of one will always be privileged over the other, creating a binary structure built upon a hunger for hegemonic power and marked by the constant threat of chaos and disharmony.

1 Quadrophenia (1979), set in 1964, also represents males in popular culture as being defined and empowered by their relationship with machinery. Quadrophenia, of course portrays the Mods’ obsession with the scooter.

2 The U.S. military parachute jumper Colonel Joseph Kittinger, Jr (b. 1928) is often considered to be the first man in space. He broke numerous records including the highest balloon ascent and parachute jump. Much of the information gleaned from Kittinger’s experiments was used to solve problems concerning escapes from aircrafts at high altitude.

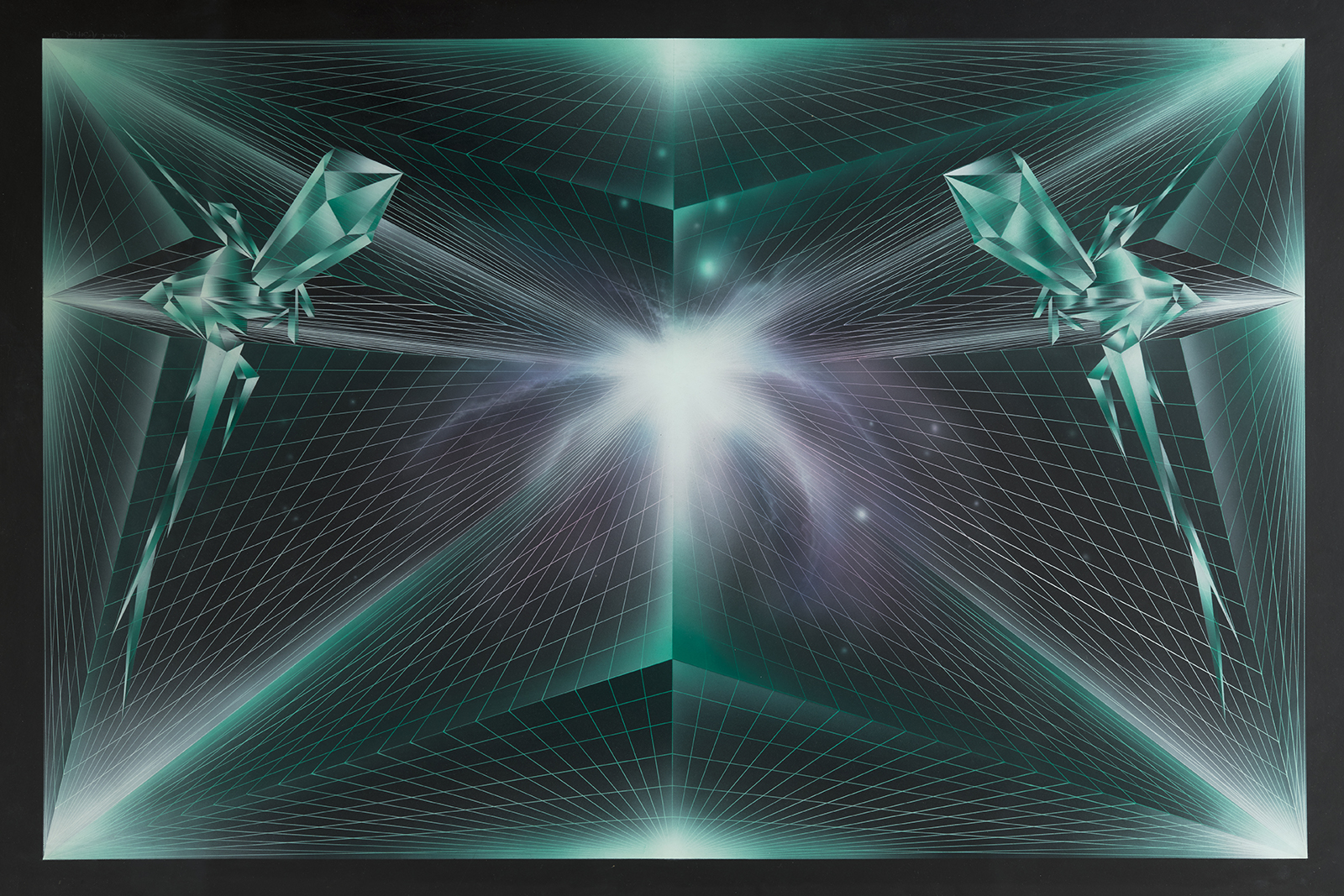

3 Situated atop the monitor were a number of silicon crystalline rocks which, in addition to being what Torben Tilly calls ‘an extract of geological time and the forces of nature‘, could be interpreted as especially relevant to the context of this show. Silicon is the basic material used in the production of computer chips, diodes and other electronic circuits, and in this context it called to mind the fact that in this post-industrial age the proliferation of information technology has contributed to shifts within the sexual division of labour.

4 Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination.Translated by Richard Nice (Stanford University Press, Chicago/London, 2001), p. 50

5 Ibid.