The Girl With The Sun In Her Head

The starting point for this exhibition was a short story by the English writer Daphne Du Maurier (1907 – 1989) first published in 1952 and titled Monte Verità. Du Maurier is an author whose work occupies a problematic place within the history of 20th century literature. Although her books have sold millions, Du Maurier’s work has ultimately been ex- cluded from the canon of literature considered worthy of critical attention. The main reason for this is that her work is usually framed within the genre of popular fiction, and viewed therefore as undeserving of ‘serious’ analysis by the literary establishment2. There can be no doubt about the fact that some of Du Maurier’s novels are somewhat anachronistic and veer into the territory of melodrama, or feature devices that keep the plot steadily paced but seem somewhat formulaic. Nevertheless, Du Maurier’s work does not fit neatly into any particular category and its popularity should not be seen as somehow indicative of the fact that her work is lacking in complexity. Her books are characterised by the intrusion of unexpectedly disturbing elements, queer subtexts and macabre twists, which do not comply with the conventions of popular fiction and give her work an arresting quality. Many of her more compelling stories end enigmatically, leaving one in a state of irresolution as to what exactly has occurred within the narrative. These aforementioned qualities that make Du Maurier’s works so singular are best exemplified in her short stories, such as Monte Verità, in which she seems most willing to transgress any literary conventions and indulge her personal proclivities. Ostensibly, Monte Verità tells the story of a young woman who abandons her husband to join a secluded and mysterious mountain sect. Throughout the narrative, the young woman’s decision to leave her previous life behind is interpreted in different ways. At one point in the story, it is suggested that she may have been brainwashed or manipulated, but it becomes evident in the course of the narrative that this woman is no abductee and has become a member of the community of her own free will. Although just over 70 pages long, this short story (which could also be described as a novella) is alluringly ambiguous and invites multiple interpretations. This ambiguous quality was one of the aspects that made Monte Verità a perfect point of departure for a group dialogue, which eventually culminated in an exhibition.

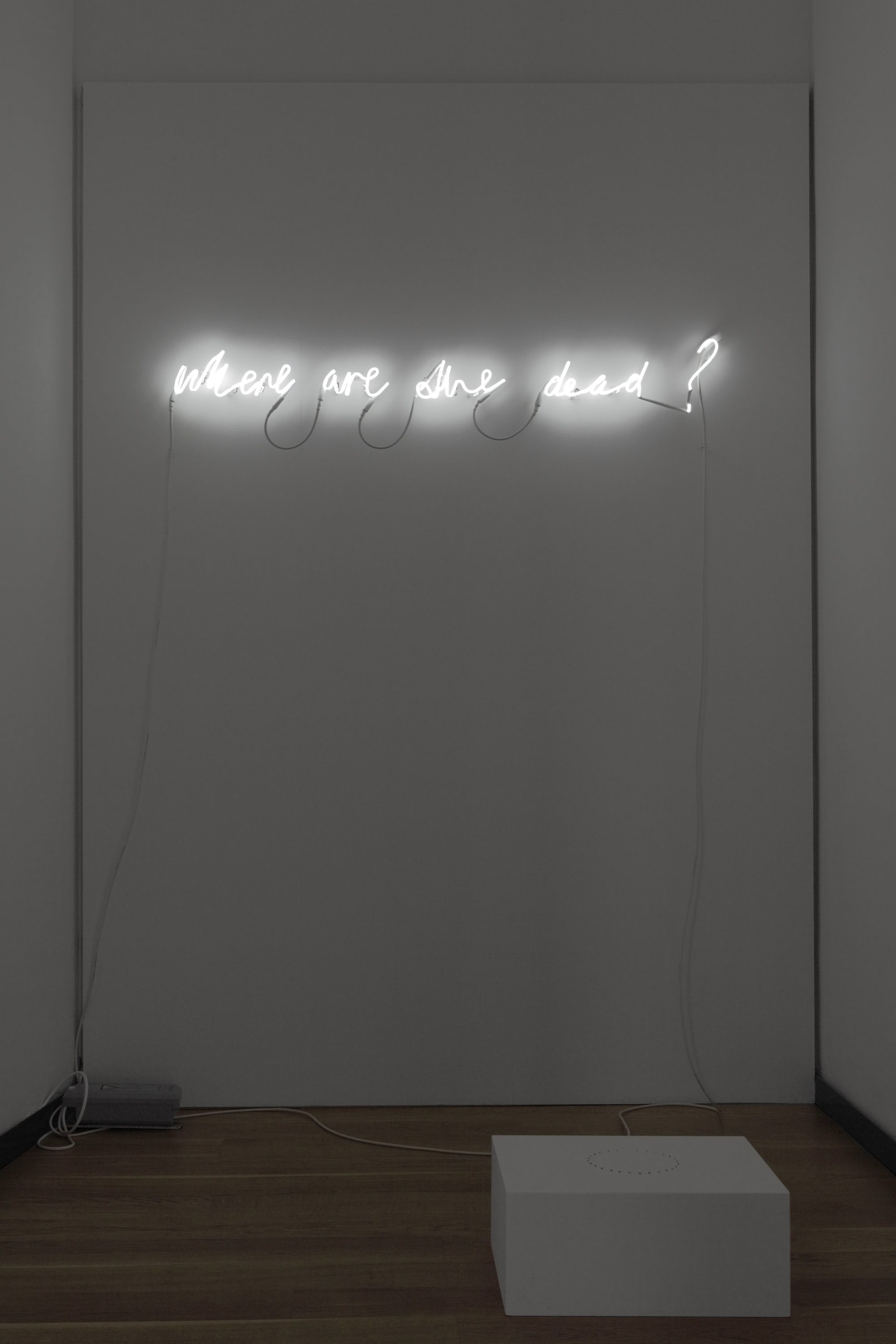

A recurring motif in Monte Verità is one of everyday life being interrupted by phenomena that cannot be accounted for logically. For example, the narrator is impelled on several occasions to act upon some uncanny and unseen forces that he cannot explain but which seem to communicate with some arcane part of his consciousness. Essentially, it is implied throughout the narrative that the techno-rational world in which we live denies the importance of (and ultimately stultifies) the faculties of intuition and imaginative perception. The emphasis upon extra sensory communication and super physical phenomenon within Du Maurier’s novella was another reason why it was chosen as the foundation to develop a group exhibition. One of the project’s intentions was encouraging consideration of the unique way that visual art can also communicate and disperse knowledge and ideas via unwritten and unspoken methods. Ultimately, the aim was to emphasise the idea that subjective intuition activated through engagement with works of art is a vital and valuable part of a person’s consciousness. Several of the artworks in the exhibition deal specifically with the way that art can create a site of pure mind and matter interaction and potentially communicate information that shapes how we perceive the world but which cannot be explained theoretically. Another theme that features prominently both in Du Maurier’s narrative and the work of several of the artists featured in the exhibition is that of religious transcendence. The life-world of the 21st century has, for the most part, forsaken the manner in which the most unanswerable questions have been traditionally appeased; that is, religion. Religion is, after all, possibly the most capable of answering a never-ending series of questions, not because its terms involve some kind of empirical justification, but rather that it shrugs the demands of empiricism itself. Religion necessitates an ambiguous movement favouring faith over proof, and mystery and devotion over under- standing and reciprocity. Dogmatic interpretations of religion have necessitated its abandonment within a society that demands the illusion of freedom. Despite religion being rejected in favour of materialist methods of approaching the unexplainable, religiosity continues to thrive in a number of forms and is particularly present within the realm of cultural production. This is evidenced explicitly in several of the artworks featured in this exhibition.

The narrator of Monte Verità is eager to conceal the location of the mountain at the centre of the novella and states: ‘there are many mountain peaks in Europe, and countless numbers bear the name of Monte Verità. They can be found in Switzerland, in France, in Spain, in Italy, in the Tyrol. I prefer to give no precise locality to mine’. However, Du Maurier’s novella was in fact significantly influenced by reality. The ‘real’ Monte Verità was a colony of artists and freethinkers founded in Ascona, Switzerland in 1900. Although the structure and ownership of the commune changed throughout its existence, it remained a Utopian community where tolerance was promulgated and various forms of creativity nurtured. Some of those who lived, worked and participated in the non-conformist colony included Hans Arp, Hugo Ball, Isadora Duncan, Otto Gross, Hermann Hesse, Carl Jung, Paul Klee, Rudolf Steiner and Mary Wigman. Significantly, a school of art was established at Monte Verità in 1913 by dance theoretician Rudolf Laban. In 1917, Laban choreographed several large- scale dance spectacles for public audiences, which were based upon the cycles of the sun and moon. It seems probable that these public performances, which took place at the commune in Ascona under Laban’s direction, inspired the sect that engages in solar and lunar rites in Du Maurier’s novella. Indeed, one can speculate that in her youth, Du Maurier – who is known to have been something of a non conformist frustrated by the gender roles imposed upon her by society – might have been attracted to the Monte Verità community, which was a renowned centre of European Bohemianism.

From today’s perspective, the colony at Ascona exemplifies the extent to which the idealism of the early 20th century galvanized people’s faith in alternative socio-political and spiritual models. However, that faith and optimism, upon which intentional communities like Monte Verità were founded, waned as the 20th century progressed and it became increasingly evident that many of the aspirations that once seemed so possible would never be achieved. If the period of frenzied development extending from the late 1890sto the mid-20th century was characterised by its tendency toward an optimistic and even blind faith in progress, then it seems undeniable that since the late 1960s this tendency has, for the most part, been inverted. The ongoing process of disenchantment, which accelerated in the wake of WWII, has resulted in the irrevocable nullification and denunciation of much of what preceded it. Even the initially fertile, critical counter movement, which emerged from the ashes of the Modernist project in the late 20th century and was characterised by a tendency to review and critique what went before, has become moribund. In the immediate present, the very notion of progress is rendered problematic and possibly redundant by the fact that we inhabit a state in which all reference points determining quality, authenticity, value and even meaning have become unintelligible. The sort of utopianism that flourished in the last century (and was concentrated in sites like the commune at Monte Verità) will never flourish again. Nevertheless, the realm of cultural production remains a place in which idealistic intentions and romantic aspirations can still frequently be found. And although art may not necessarily be able to change the world, it can still be a catalyst for change and a sphere of potential. Indeed, the decision to use Du Maurier’s novella as the starting point for this project was intended to encourage those involved to consider the parallels between the ‘real’ community upon which Du Maurier’s novella is based and the Van Eyck Multiform Institute. Despite the many obvious major differences between these communities, both were built upon and around openness, dialogue, exchange and the necessity to create a space of egalitarian togetherness that defends contemplation and cooperative enthusiasm.

A key stage in the project’s development involved all project participants engaging in a close reading of the elusive novella. This pragmatic process was an integral and essential facet of a curatorial strategy, which entailed formulating questions via in-depth analysis and appreciation of the artistic positions of the individuals involved. Within this strategy, the novella came to function as a conduit through which those involved could access and explore a shared topography and communicate via a common language. Each independent reading of the text resulted in the emergence of a subjective constellation of images, motifs and moments, which held a particular significance for each individual. In some cases, these elements found their way into new works produced specifically for the exhibition. In other instances, the novella became a lens through which artworks produced prior to the project could be viewed in a new light. In this way, the artworks and the text became symbiotic entities. Included alongside this text are excerpts from conversations with the artists involved in the exhibition which reveal some of the resonances between their works and Du Maurier’s story. Some of the issues and urgencies at the centre of the participating artists’ practices are also discussed. It is perhaps no surprise that the dialogue (of which these excerpts were a part) crystallized into an exhibition that is as open-ended and as rich with meaning as the novella that provided the point of departure.

1 The title of this project was taken from ‘The Girl With The Sun In Her Head’, a song recorded by the pioneering electronic band Orbital using the Greenpeace solar generator CYRUS in 1995. The song was dedicated to the memory of the young photographer Sally Harding who died in 1995 and had prior to her death been one of the few people documenting the then radical subculture associated with the burgeoning dance music scene in the UK. The title is redolent of the imagery in Du Maurier’s novella, in which the protagonist, who renounces her rather conventional life to join the Monte Verità sect and worship the lunar and solar deities, quite literally has the sun in her head.

2 Her known works are probably those that have been adapted into films. Five of Du Maurier’s novels have been adapted. These are: Jamaica Inn, Rebecca, Frenchman‘s Creek, Hungry Hill, and The Scapegoat. In addition, two short stories, The Birds’ and Don‘t Look Now have been very successfully adapted for film: the first by Alfred Hitchcock in 1963 and the second by Nicholas Roeg in 1973.