Let the Dead Leaves Fall

In The Sociology of Religion, written in 1920, Max Weber argued that changes occurring in the western world were having a profoundly negative impact upon the psychological and spiritual state of the individual. Weber believed that an increase in the tendency to prioritize scientific rationality over faith and intuition, combined with the rise of technological objectivism, was leading to a world devoid of enchantment. As a consequence, many people suffered from a sense of disillusionment, emotional isolation and spiritual hunger. In the century since the publication of The Sociology of Religion some of these symptoms of disenchantment have certainly become more prevalent, however, a variety of phenomena and impulses which oppose the supremacy of a techno-rational worldview have flourished. This is particularly evident within the sphere of visual art which in recent years has seen a proliferation of interest in totemism and in the animism of physical objects. There is also an increased tendency amongst visual artists to utilize aesthetics and strategies from ‘new religious movements’ which have emerged over the past half century. Miguel Martin’s exhibition Let the Dead Leaves Fall evidences these contemporary tendencies and interests. Indeed, the entire aesthetic of Martin’s exhibition demonstrates a proclivity for visual vocabularies which have been significantly influenced by several new religious movements.

Although each of the artworks in Let the Dead Leaves Fall can be interpreted individually and possess their own particular resonance, this exhibition was conceived to be read as a unified whole. The various components of the exhibition are analogous to the elements of a mise-en-scène; a theatre set with props that invite the viewer to devise their own narrative or interpretation. One of the intentions that informed Martin’s thinking in developing the exhibition was that the encounter would be an experience for the senses as well as the intellect; impacting the audience on a phenomenal level as much as a cerebral one. This is demonstrated in the work Downward Dog Not Spiral which features strobe effects and sounds that impact the viewer on a somatic level. One could consider this work as the fulcrum of the exhibition in that it is comprised of images and information which influence how one might view the other pieces in the exhibition. It is this work which provides us with the unifying threads from which we can piece together a narrative.

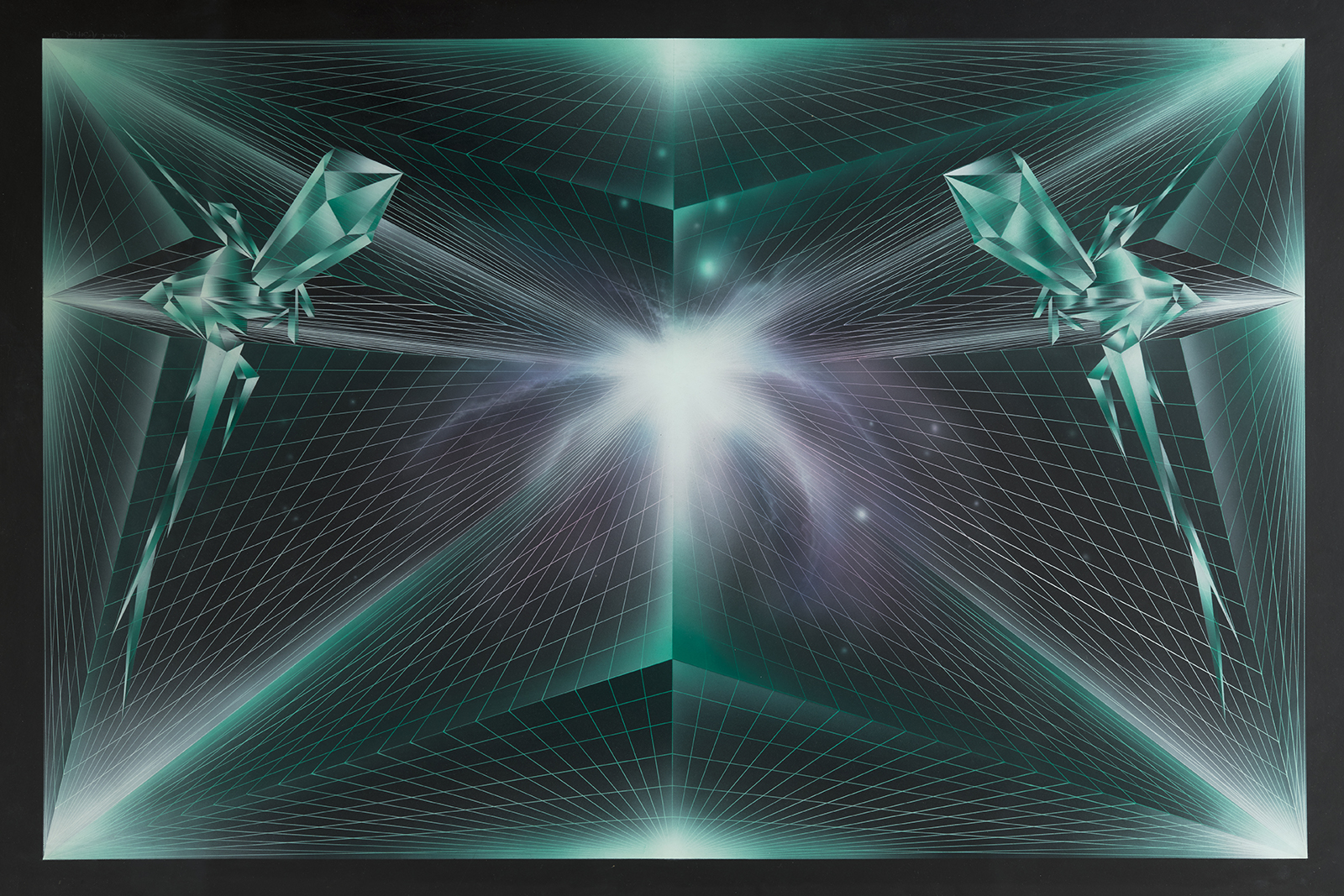

With this exhibition Martin enters a lineage of artists who have conceived fictitious secret societies or religious orders as a means of aesthetic inquiry (1). The works in Let the Dead Leaves Fall point to the existence of a cultic organisation; the installation appears as a site of worship and ritual. Viewed together, the various components that make up this installation provide insights into the character of the cult that Martin has conceived. It would appear that they are seeking to attain spiritual enlightenment and transcendence via a combination of yogic practices, ritual magic, self-help psychology and masonic symbolism. We encounter a guru or spirit guide whose attire is comprised of sportswear coupled with the sort of masks worn by shamans who carry out healing rites in order to guard themselves from diseases they may contract. The mysterious hand gesture that we glimpse in the final moments of Downward Dog is evocative of those used by rabbis and those used within certain masonic orders. It recurs again in the sculptural installation Second Sight that appears as a reliquary, a shrine room or perhaps a site of initiation. In the context of this exhibition the hand gesture refers to the secret handshake or visual cue that members of a secret society or covert faction use to communicate with one another.The group of untitled still life drawings by Martin sheds further light upon this secret sect; we see disciples in attire that is similar to that worn by the guru figure, their garments appear as vestments with a ceremonial purpose.

Two themes are particularly prevalent within this exhibition: the role of fitness and health culture in contemporary society and the proliferation of certain aspects of that culture which have become fundamentally tied to notions of metaphysical enlightenment. Awareness of the life-improving effects of physical fitness has grown in recent decades and it could be argued that physical exercise has begun to fill the spiritual vacuum that might have once been satisfied through forms of religious worship, particularly since certain types of physical exercise have become conflated with ideas of spiritual enrichment. This is touched upon in the work Are You Sure You Want to Quit? Which comprises a sculptural form resembling a yoga mat made from black nero marquina marble, imbuing what is for some an everyday object used in the pursuit of enhanced physical well being with a sacred aura. Downward Dog features a collage of audio recordings, several of which were sourced from YouTube. The collage includes excerpts from a speech by ‘motivational speaker’ Simon Sinek as well as a section of diatribe from a particularly devout Christian claiming that those who practice yoga run the risk of demonic possession. However, the most prominent section of this audio was recorded by the artist in the occult section of a London bookshop. We hear the voice of one is who presumably some form of adept declaring, albeit in vague terms, the benefits of engaging in a ten-day fast from food and all electronic devices. The unidentified speaker repeatedly states the benefits of such a fast, and declares how it burns up a lot of the stuff that you’ve already got. This could be a reference to either – or both – the resolution of emotional baggage and the burning of excess calories.

The title of the exhibition is based upon the words of thirteenth- century Sufi poet and scholar Jalal al-Din Rumi (Be like a tree and let the dead leaves drop) and the practices depicted in Let the Dead Leaves Fall refer to Eastern traditions such as yoga. The transformative catharsis which the protagonist of Downward Dog undergoes looks much like the process known amongst yogis as mahasamādhi; the exiting of one’s body in a state of ultimate enlightenment. However Martin also looks to some of the more aggressive forms of fitness culture which has emerged in the West over the past century. While it may seem like a relatively new phenomenon, the conflation of fitness and religious tendencies dates back to the late 19th century and is most explicitly manifest in a movement that emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1880’s known as Muscular Christianity. This movement was constructed upon perceived connections between ideas of godliness and physical fitness, and it preached the idea that physical exertion served to cultivate both morality and masculine characteristics, both of which were viewed as desirable and superior. Recent decades have seen a dramatic increase in churches, mosques, synagogues and other religious communities promoting what has become known as ‘faith-based fitness’. This practice is particularly prominent in the United States where ‘megachurches’ are frequently equipped with major sports complexes and gymnasiums for the laity. Magazines such as Faith & Fitness and websites such as ChurchFitness.com offer information to churches on how they can establish gyms or fitness spaces. Conversely, in Ireland several churches have been desanctified and converted into gymnasiums; similarly demonstrating how awareness of the potential benefits of physical fitness has increased as devotion to traditional modes of worship has declined.

Martin also makes reference to the manner in which vague notions of wellbeing have become inextricably intertwined with identity. The ‘altar cum billboard’ emblazoned with the directive to Search Inside Yourself is situated in the main exhibition space. It is a simulacra of a billboard positioned outside a church which Martin passed frequently originally bearing the company name Million Dollar Fitness. ‘Search Inside Yourself’ is the title of the mindfulness training programme founded by Google engineer Chade-Meng Tan in 2006, taught to Google staff in 2007 and thereafter quickly adopted internationally. The programme’s focus is on mindfulness, emotional intelligence and resilience. According to Google, the mindfulness training programme was born at Google from one engineer’s dream to change the world (2). Google states that Tan’s position requires him to enlighten minds, open hearts, create world peace (3) and states that the incredible success of Tan’s influential curriculum led to him being given the title of ‘Google’s Jolly Good Fellow’.

For the most part, the SIY programme can be viewed as an attempt by a major corporation to maximise the wellbeing and productivity of its workforce. While many attest to the positive benefits of the SIY programme it is difficult not to feel somewhat suspicious of the rather righteous entity spawned by Google which claims to contribute to world peace or at least peace and harmony in the workplace (4). Perhaps to some extent one can see in this a return of the internet to its 1960s roots – many of those who pioneered and developed the underlying technology to the internet were deeply involved in various forms of esotericism.

Several of the tropes of Martin’s exhibition echo the Heaven’s Gate religious community. Martin references this cult in his exploration of the relationship between technology and modern forms of worship. Heaven’s Gate was a religious community who lived together for several years before committing suicide en masse over two days in March 1997. Members of the community were adept in their advanced understanding of the potential of the internet at a time when it was far from the quotidian tool that it has now become. One of the details the media frequently emphasised in its reporting of the Heaven’s Gate suicide was that the community subsisted on finances collectively earned as web designers for their company Higher Source. In the days when the very idea of the world wide web was still loaded with utopian possibility, Heaven’s Gate cult were leading web-designers combining their technological acumen with mystical fervour. At the time of their suicide there was a genuine widespread anxiety that such new religious movements were actively recruiting members via the Internet. The clothes worn by the protagonist in Downward Dog could be described as urban streetwear meets shamanistic garb and they bear more than a slight resemblance to the outfits worn by the Heaven’s Gate cult. Forensic photographs taken at the mansion where the thirty-nine members of Heaven’s Gate lived and died famously featured each member in the same uniform, with the same black pants and prominent Nike sneakers. Moreover, the protagonist in Downward Dog appears to share the intention of the Heaven’s Gate members to free themselves from their bodies and depart earth for another plane.

In conversation, Martin repeatedly mentions his interest in horror movies and the atmosphere of this exhibition is significantly influenced by his appreciation of the genre. Although the title of this exhibition is sourced from Rumi’s quote it is also evocative of titles given to Italian Giallo films (5). This exhibition also evidences the artist’s interest in the aesthetics and the atmosphere of the uncanny. The uncanny has been a major theme in art – especially Gothic literature- since the late 18th century, but it is Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay Das Unheimliche that has most significantly shaped contemporary ideas regarding the phenomenon. Freud’s list of factors that turn something fearful into something uncanny can be identified in Martin’s exhibition: animism, magic and witchcraft, the omnipotence of thoughts, man’s attitude to death, involuntary repetition and the castration-complex (6). Moreover, Freud defines the uncanny as that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar (7) and perhaps on some level the exhibition stirs memories of events occurring not too far from Portadown in the early 1970s, allegedly animal sacrifices and black masses. It remains unclear whether or not these reports were the result of a paramilitary psychological operation (what could be referred to as a Black PSYOP) or if there was in fact occult activity but either way the rumours of Satan Worship and ritual sacrifice were rife in an episode of public anxiety that seemed to presage the satanic panic of the 1980s.

Ultimately, Let the Dead Leaves Fall can be read as a reflection upon the complicated and convoluted relationships that society has with ideas surrounding bodies, belief systems and self identity. While Martin himself has positive personal experiences with practices such as Transcendental Meditation, the various components that make up this installation express an ambivalent position on this subject matter. The exhibition undoubtedly focuses upon some of the dubious aspects of highly commercialised new-age culture and à la Carte spirituality. However, it would be a mistake to view this exhibition solely as a critique or even as an attempt to address certain anthropological issues in academic terms. Ultimately, this exhibition is intended to be encountered experientially; the viewer navigates various zones and endures darkness and disorientation punctuated by insights and the acquisition of knowledge in a process that could be likened to an initiation. Essentially, this might be considered as an allegory for the process of self-actualisation, something for which devotees of the various doctrines referenced by Martin in this exhibition seem to be searching.

(1) The strategy employed by Martin in this exhibition is not dissimilar to that employed by Jim Shaw in the creation of the pseudo religion which he titled O-ism. According to Shaw, who produced work under the O-ism as a kind of pseudonym, O-ism dates back to the mid 19th century and theology centres on a goddess who may not be named and who is referred to only as “O”. Shaw devised O ism as a means of bringing together disparate aspects of American culture such as Mormonism and particular aspects of American modernism.

(2) Search Inside Yourself, accessed October 2017: https://siyli.org/about

(3) Chade-Meng Tan (Meng), accessed October 2017: http://chademeng.com/about/bio/

(4) Search Inside Yourself, accessed October 2017: https://siyli.org/about

(5) Examples of titles of Giallo Movies include; Hatchet for Honeymoon, The Case of the Bloody Iris, The Case of the Scorpion’s Tale, The Flower with the Petals of Steel

(6) Freud, S. (1999). The “Uncanny”. In S. Freud (Ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works (pp. 217-256). London: Vintage. (Originally published in 1919) p243.

(7) Ibid.