Notes on Duchamp’s Green Box; A Patrilineage

Although referred to most often in relation to his readymades, Marcel Duchamp’s magnum opus — and the work that has attracted most analysis — is the enigmatic La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même [The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even], aka The Large Glass. Since its completion in 1923, the imagery and information contained within the work has been the subject of considerable conjecture. Many have attempted to decipher its symbolism, but while numerous interpretations have emerged, it is widely agreed that the work is a schema of sexual desire. Much less attention, however, has been given to the work Duchamp completed eleven years later, entitled The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. The Green Box, which was intended as a companion to the earlier work. Consisting of preparatory notes, sketches and photo- graphs pertaining to the conceptual development and fabrication of The Large Glass, The Green Box was produced as an edition of 300 and issued under the name of Duchamp’s female alter-ego, Rose Sélavy (1). As with The Large Glass, the imagery in The Green Box comprises mechanical devices and scientific graphs with erotic implications. Duchamp’s seem to be engines powered by invisible, magnetic forces of desire.

The contents of The Green Box, and the techniques used in its production, can be viewed almost as a collection of all of Duchamp’s best-known tactics. Importantly, the fact that the contents of the box are unbound allows its owner to engage in the act of creation: deciding in what order to read or arrange them. Despite being a multiple or serially produced artwork, many sheets within the box appear as though they have been spontaneously handwritten. These sheets were intended to underscore Duchamp’s aim of producing art ‘in the service of the mind’, as opposed to a purely visual or ‘retinal’ art (2). The notes in The Green Box offer insights into The Large Glass that may or may not be decoys or mistruth. Either way, the work elevates the legendary status of its author and reveals the extent to which Duchamp engineered a mystique around his legacy. Indeed, it is with The Green Box that the cult of Duchamp begins in earnest.

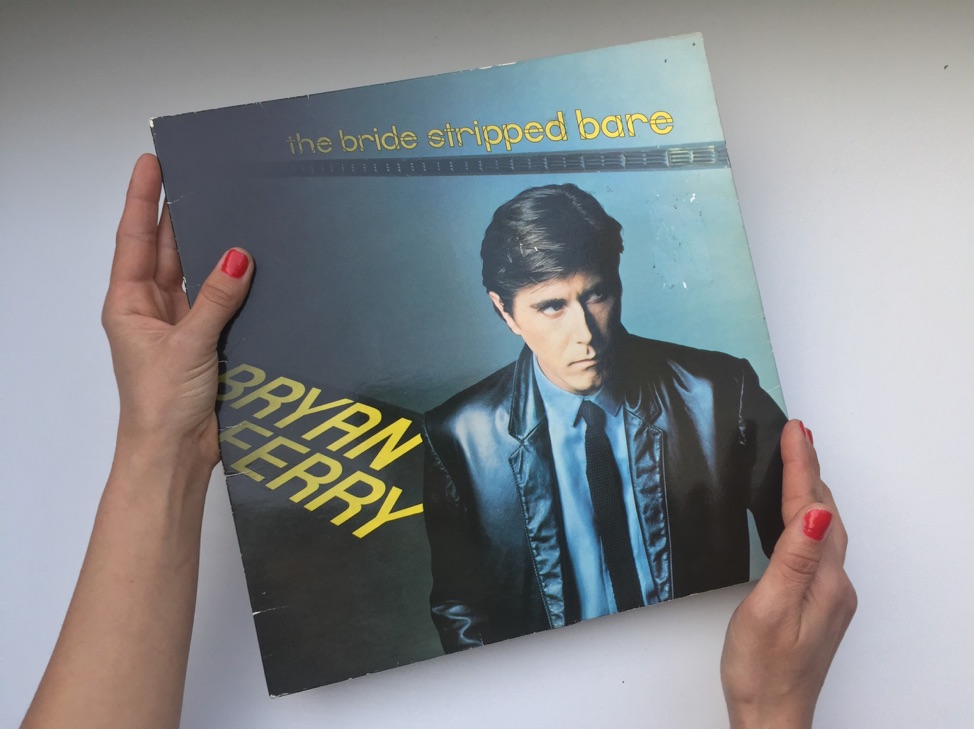

The most avid disciple of this cult of Duchamp was undoubtedly Richard Hamilton, who spent much of the 1960s painstakingly (re)producing his version of The Large Glass (3). The Green Box was vital to Hamilton in this process: he used its contents as an instruction manual. At the same time, Hamilton was absorbed with pioneering Pop Art and examining how consumer society depends on the manufacturing of desire through design (4). Hamilton used images of consumerism as a means of playfully critiquing the apparatus of capitalism in post-war society. He was fascinated by the titillating charge of glossy surfaces and seductive images, and how they could be used to arouse a desire to engage in commercial transactions. This preoccupation led Hamilton toward a very specific analysis of Duchamp’s Green Box (5). For Hamilton, desire is anchored in and connected to the movement of capital, while commodity fetishism and sexual fetishism are almost entirely conflated. In the years that Hamilton was most absorbed by his reproduction of The Green Box, he worked as a tutor at Newcastle University. There, one of his students was a young Bryan Ferry. The two first met when Hamilton was in thrall to Duchamp’s enigma and preaching his concepts in art class. From Hamilton, Ferry learned that the aesthetics of one realm (advertising) could be appropriated and applied to another (fine art), and began making paintings of mechanical brides and erotic automobiles. This set Ferry on (an initially fruitful) path in which he reversed this aforementioned formula, taking concepts from the avant-garde and applying them to the realm of popular music. Ferry, who often reinvented himself (via carefully conceived image changes), became known for producing albums consisting almost exclusively of cover versions of well-known songs. In these instances, the material that he selected for recording was treated as a readymade. This is most explicit in Ferry’s The Bride Stripped Bare (1978), his fifth solo album to be released independently of Roxy Music. Fusing cover versions with slick sleeve design and a measured frisson of avant-gardism, Ferry distributed staunchly heterosexual and narcissistic dreams of desire to vast audiences. In an interview given in the 1990s, Ferry suggested it was he who was Hamilton’s greatest creation (6) framing himself as an alchemical hybrid of his two fathers. When we consider how Hamilton had (in the late 1950s) envisaged what Pop Art would eventually become, it seems as though Ferry was modelling himself directly upon Hamilton’s description of it: Popular (designed for a mass audience) Transient (short-term solution) Expendable (easily-forgotten) Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business (7). Several of the strategies that Duchamp introduced into the realm of visual art altered the definition of artist from one who fabricates to one who selects. This is touched upon in one of the notes contained within The Green Box (entitled ‘Specifications for Readymades’) which states that the readymade is a kind of rendez-vous (8) between an object and an author. Aware of the potency of mythology, Ferry adopted and modified strategies that originated with Duchamp, but there is a simplification — and flattening out — of them, too. The boundaries between critique and playful complicity vanishes. Ferry’s 1978 album exemplifies how ubiquitous Duchamp’s ideas had become just ten years after his death; the continuum of a process started by Duchamp in which strategic selection and mass dissemination of pre-existing material become the vital thrust in the creative act. It also reveals the extent to which the potent ambiguity and self-reflexivity of Rose Sélavy is neutered and sanitised. Industrially reproduced and disseminated en masse, The Bride Stripped Bare of 1978 is merely a seductive surface image (see images), engineered to arouse a desire that stimulates the movement of commodified units.

1 Marcel Duchamp created the fictional female character Rose Sélavy in 1920 and viewed both the character and the works she generated as autonomous works of art. The name is a pun on the phrase ‘Eros, c’est la vie’ (‘Eros is life’, and also ‘Eros, that’s life’).

2 Duchamp as quoted in H.H. Arnason & Marla F. Prather, History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography, 4th edition (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998), p.274.

3 Hamilton first met Duchamp in 1958 and became a close associate. In 1966 Hamilton organised the first British retrospective of Duchamp’s work at the Tate Gallery. With Duchamp’s permission, Hamilton reconstructed The Large Glass for this exhibition.

4 Hal Foster, The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton…,p.55.

5 Hamilton published the first typographic translation of The Green Box in 1960.

6 See http://bryanferry.com/richard-hamilton. Accessed on 20 May 2019.

7 Postcard from Richard Hamilton to architect Peter Smithson in 1957.

8 Michel Sanouillet & Elmer Peterson (eds.), Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), p.32.