We New Traditionalists (excerpt)

Sketches of Universal History Compiled from Several Authors by Sarah Pierce presents an interplay of voices, legacies, friendships and influences that make up an art practice. Conceived from a period of collaboration between the artist, curator and writer Rike Frank, with publishers Book Works and The Showroom, the book contains newly commissioned essays by Melissa Gronlund and Tom Holert.

Following the American sociologist C. Wright Mills’ suggested practice of filing the ideas that compel you, then periodically unpacking, shuffling and spreading out the contents in search of new connections, each section of the book proposes routes through ten years of material. Facsimiles of conversations, letters, clippings and other source documents, on events that range from student protests at Kent State University in 1971to student debates on the State of British Art in 1978; the work of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin; Charles Harrison’s letters from When Attitudes Become Form, poems by Allen Ginsberg, and Lucy Lippard’s photo captions on the work of Eva Hesse, all revealing processes of research and a continual renegotiation of the terms for making art.

The material is gathered from Pierce’s ongoing and expansive exhibition projects that use archives, performance, discussions, and installation with sound and video elements. Presented as a monograph, the book draws on Pierce’s own biography as an artist, her history and ‘progress’, as well as historical and counter-cultural references, and the proximities of past artworks, that frame her work.

In 2003, Pierce began using an umbrella term, The Metropolitan Complex, to describe her art practice as articulated through multiple voices and collective inputs. Much of her work stakes a claim on the incidental or peripheral conversations and gestures that surround cultural work, as the sites of dissent and self-determination. Sketches of Universal History Compiled from Several Authors by Sarah Pierce provides a comprehensive insight into the complexities and slippages between individual drive and institutional context. An abridged chronology reflects the community of curators, students, archivists, reading groups and artists who have been direct interlocutors in Pierce’s practice.

We New Traditionalists

Pádraic E. Moore and Sarah Pierce

“Every era has to reinvent the project of spirituality for itself.

(Spirituality = plans, terminologies, ideas of deportment aimed at the resolution of painful structural contradictions inherent in the human situation, at the completion of human consciousness, and transcendence.)”

Sontag – The Aesthetics of Silence (1969)

The point of departure for this text is a project developed by Sarah Pierce between 2006-2008 titled The Meaning of Greatness.

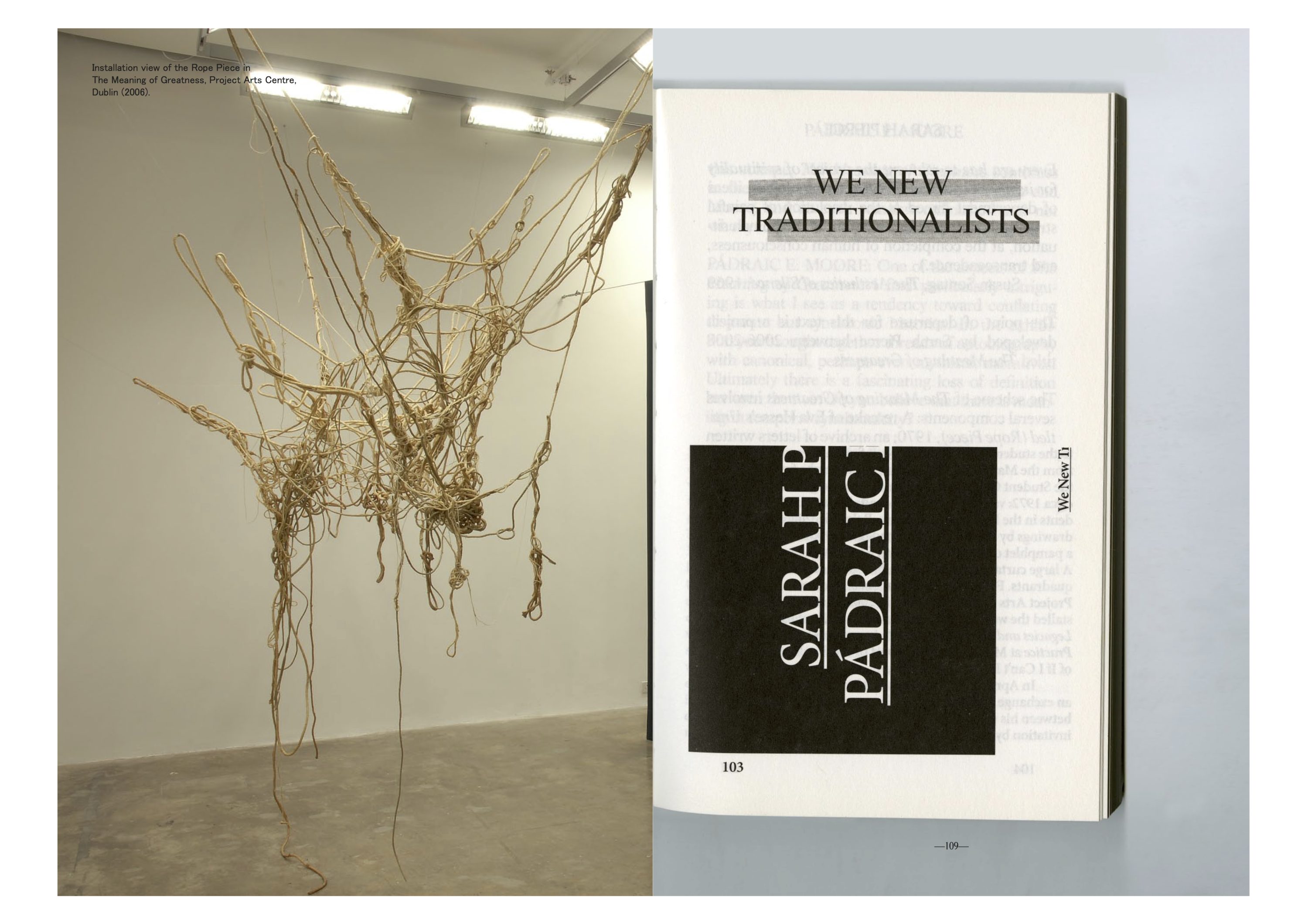

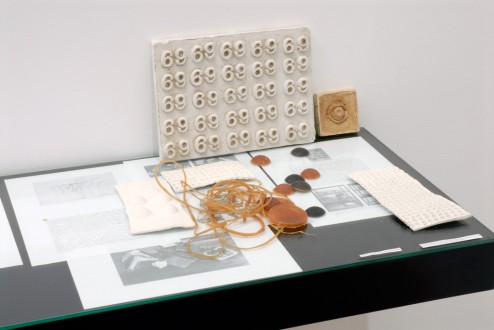

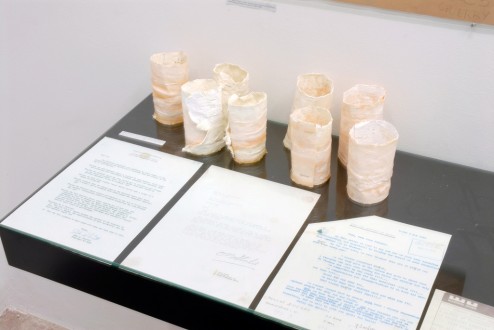

The scheme of The Meaning of Greatness involves several components: A remake of Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970 by Eva Hesse, an archive of letters to the student government at Kent State University from the May 4, 1970 collection, photographs from the Student Cultural Centre Archive in Belgrade (c. 1972), various ‘test pieces’ made by art students in the Faculty of Sculpture, Belgrade (2006), drawings by Pierce’s mother (c. 1956), a pamphlet of texts selected together with Grant Watson, and a large curtain which divides the exhibition space into quadrants. Sometime after the initial installation of the Meaning of Greatness at Project Arts Centre in Dublin (2006), Pierce reinstalled the work as part of the exhibition Feminist Legacies and Potentials in Contemporary Art Practice at MuHKA Antwerp, part of Edition II of If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution.

In April of 2008, Padraic E.Moore initiated an exchange with Pierce with regard to parallels between his own work and hers; an invitation Pierce responded to by inviting Moore to contribute to this volume. To some extent, The Meaning of Greatness continues in the conversation between Pierce and Moore, and as such remains unfinished and not wholly formed.

PEM: One of the aspects of the Meaning of Greatness I find particularly intriguing is what I see as a tendency toward conflating disparate but synchronic histories. In the exhibition you married [nice]autobiographical threads with canonical, perhaps even mythical, narratives. Ultimately there is a fascinating loss of definition between the two. Do you believe that there is meaning in temporal synchronicity?

SP: I’m remotely familiar with synchronicity as a concept as it occurs in Jungian psychology – where there is meaning for the individual in events that occur together. I’m interested in things that are not causally related, where temporal proximity allows for meanings to emerge that are not historical or contingent, but rather that hinge on a certain recognition of the conflicts or contradictions present in ‘knowing’. So with synchronous events, knowledge is not synthesis as in unification (which is, I think, inconsistent with dominant notions of synchronicity). Knowledge is closer to what Sergei Eisenstein describes in Film Form, when things come together, often in conflict, to produce meaning. Meaning is never, can never be autonomous. The site of knowledge is a site of ‘undoing’ whereas events are revealed through incidental, coincidental and causal patterns that we typically use knowledge for to obscure or suppress. This way of knowing is not a call for irrationality over rationality; it is more about an intellectual thinking where knowledge occurs through disorder and unrest rather than through rationalizing (and historicizing and bureaucratizing) tendencies.

PEM: In the case of the artist, the tragedy of the premature death can result in a situation whereby an archetypal, almost mythological quality is posthumously assumed. This process is invariably abetted by the circulation or re-emergence-of artworks and images, resulting in the prematurely departed artist achieving something approaching ubiquitous presence and immortal status. A thread runs throughout your previous work that evinces a preoccupation with the work of antecedents such as Eva Hesse (1936-1970), Robert Smithson (1938-1973) and Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978). You seem to share with me an interest in considering the way in which these premature departures often alter the lens via which an author’s work is posthumously viewed.

SP: What you are getting at reminds me of Derrida’s idea of secrecy and sacrifice in The Gift of Death, and I think it is important to note that there is an ethics at play in art history, especially as it occurs through the museum, when we infuse an artist’s work with tragic tones. Dying young is tragic, but the lives of the three artists you mention were not tragic; their work certainly isn’t about tragedy. There is a section in Anne Wagner’s essay “Another Hesse,” that describes Hesse’s journals and how to read them. Wagner points to various instances, from catalogue texts to reviews written after Hesse’s death, where biographers and critics have turned to the artist’s journals to find meaning in her work. What is read as the tragedy of Hesse’s death becomes a legacy of feminine genius of her work. However, were we to read Hesse’s journals in the context of her life (rather than her death), we might discover a different Hesse, someone less “damaged and chaotic” (words that have been used to describe both Hesse and her work) than we imagine. Read uncut, the journals are, in places, about as remarkable as the lists Hesse scribed to organise her time. Time spent on ‘us’, meaning her marriage, and ‘me’, meaning her career. As Wagner notes: This fact does not make her work less significant, but it does make some of the writing about her work by others since her death less potent. Her choices betray any kind of universalised feminism. In one of her journals Hesse wrote, “Excellence has no sex.” I often think about this comment in relation to a doctrine of feminist thought prevalent in the 1960s and to notions of being an artist that persist today.

Sarah Pierce, Installation detail (curtains, rope, archival materials, photographs from the SKC archive, Belgrade; letters from the May 4 Collection, Kent State University, drawings by Anne Guerry, test pieces by students from the University of Belgrade.) Commissioned for a solo exhibition at Project Arts Centre, Dublin. Curated by Grant Watson. Collection of Irish Museum of Modern Art. 2006

PEM: I think it would be inaccurate to consider your work nostalgic. For while you do reference, celebrate, perhaps mourn, events and occurrences of the past you also highlight that these events and occurrences remain loaded with potential. Though well aware that notions of progress and temporal linearity are inherently problematic and indeed contentious, I believe that they remain not only valid but also essential. Am I correct in assuming that it is not your desire to reside in an idealized notion of the past but to progress forward via a process of excavation?

SP: In “The Sociological Imagination” (1959), American sociologist C. Wright Mills talks about the interdisciplinary aspects of intellectualism, and the practice of keeping a file, or set of files, with all the ideas or materials that compel one’s research. He recommends periodically spreading the contents out and arranging them to figure connections between them. In some ways, The Meaning of Greatness is such a ‘file’.nice Convened temporarily, it is driven in places by merely coincidental affiliations, but these lead to unexpected readings often immersed in dissent and self-determination. These events or occurrences already exist next to one another, and this proximity has a potential to produce undertonal meaning. Again, I’m referring to Eisenstein. Undertonal meaning exists in between images, between the events of remembering and forgetting. With archeology there is a danger – as Eisenstein warns in relation to cinema, and Foucault describes in Historical a priori and the archive where the dominant purpose, the a priori, if you will, works in contradiction with the undertones.

PEM: Do you believe that in general the notion of progress has been problematised?or does he mean: is problematic?Problematising means if I’m right that something is subject of discussion.

SP: The first sentence of a short story by Yukio Mishima begins, “On the twenty-eighth of February, 1936…” The events unfold: a soldier returns home to his young wife and in his loyalty to his country and her loyalty to her husband both end their lives by committing seppuku. The story is inextricably linked in my mind to my mother because her birthday is February 28, 1936. It’s merely a coincidence. This is how I think of progress. Moving through events we muddle meaning, we conflate circumstances, and we tend to find temporal synchronicities with significance to us. Mishima’s story is called “Patriotism”, a term which, like Derrida’s concept of responsibility, requires arbitrary and incoherent irrationalities also found in sacrifice. [as you refer again to Derrida’s idea of sacrifice here, I would definitely explain it a little bit at the beginning of the text]In Mishima’s words:

“Was this seppuku? —He was thinking. It was a sensation of utter chaos, as if the sky had fallen on his head and the whole world was reeling drunkenly. His willpower and courage, which had seemed so robust before he made the incision, had now dwindled to something like a single hairlike thread of steel, and he was assailed by the uneasy feeling that he must advance along this thread, clinging to it with desperation. His clenched fist had grown moist. Looking down, he saw that both his hand and the cloth about the blade were drenched in blood. His loincloth too was dyed a deep red. It struck him as incredible that, amidst this terrible agony, things, which could be seen, could still be seen, and existing things existed still. […]” As with our soldier, at times blind conviction is our downfall. The moment we think we are on the right path, in the next moment might turn to terrible doubt and chaos.

PEM: Much of your work reflects upon moments or situations of politically engaged counter cultural activity. Would you agree that as we shift into an increasingly incredulous future – in which chronologies are compressed and time is accelerated- encountering and contemplating, indeed vicariously accessing such moments can facilitate temporary diversion from the anomic present in which we flounder in a state of political abstinence and in which ideals of revolution and progress have been rendered problematic?

SP: Yes, we flounder, we accelerate, and perhaps we stall. The ideals of revolution and progress are as problematic as a notion of legacy and ‘the cult of genius’, found in art. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In posing this question in 1988, Linda Nochlin cautions us not to take the bait. Take pause! Before petitioning a list female names to add to the canon, consider why is it so difficult to retire the canon altogether. In Belgrade there is a wood near the university where Milosevic began the construction on a Museum of Revolution. Only the foundation exists; the museum was never built. It is a space that preoccupies many artists who visit Belgrade – it is so prime for interpretation! Visiting Belgrade in 2006, I arrived during the week of Milosevic’s funeral. When I went the university’s Faculty of Sculpture, I met with the second and third year sculpture students, and looking around their studios, I was drawn most to the ‘test pieces’ — preliminary studies for future works that tryout an idea or test the properties of certain materials. I knew from studying the work of Eva Hesse, that she sometimes exhibited small non-works, or non-pieces – the 3 dimensional tests for larger sculptures. In her biography on Hesse, Wagner introduces her study of the artist through a question. She asks, “What does Hesse’s art look like?” It was with this question in mind that I proposed an exhibition in the SKC gallery of these unfinished works. Some of the students’ test pieces are remarkably like Hesse’s in both their materials and form. It was during this period of research that I began to think about the associations between 1970s radical art practices and a present student body.

Sarah Pierce, Installation detail (curtains, rope, archival materials, photographs from the SKC archive, Belgrade; letters from the May 4 Collection, Kent State University, drawings by Anne Guerry, test pieces by students from the University of Belgrade.) Commissioned for a solo exhibition at Project Arts Centre, Dublin. Curated by Grant Watson. Collection of Irish Museum of Modern Art. 2006

PEM: Your work consistently raises questions and problematises ideas of originality and authorship while also -paradoxically- corroborating a kind of pantheon via reconstitution. Are you interested in the idea of a canon?

SP: Instead of a canon, imagine a more affectionate past. Formative and unfinished, not yet art, not in the realm of the documentable. This is a concept that I’m working on at the moment – a relationship to a past that is not Oedipal or forged as critique. Wagner writes: “The wish to know Hesse is deeply nostalgic: it voices the desire for a return to the past to recover the Hesse who disappeared there, the woman who in 1970 died of a brain tumor at the age of thirty-four. She is the only Hesse we have, after all. […]” Perhaps my desire to know Hesse is no less nostalgic; my mother and Hesse were born in the same year. They grew up a few miles from each other; both come from families with moderate incomes and educated parents, each attended Ivy League schools, pursued classically ‘female’ majors, and were married within a few years of each other. Reading Hesse’s biography I am also reading about my mother. It’s perhaps then narcissism when we imagine someone’s life through its potential to reflect us, to us. And isn’t that how a canon works?

PEM: This epoch in which we are living is rather chaotic for the fact that numerous historical fragments drift randomly out of context, ultimately creating a kind of amnesiac present. Do you feel compulsion, as I often do, to order history and received information concerning the past and, if so, is this ultimately an attempt to impose a sense of order or clarity upon the chaotic present?

SP: Returning to Eisenstein, every film is infused with a ‘fourth dimension’. Perhaps an ‘archival fourth dimension’ describes[ing?] connections, both material and formal, that incite a contest between time and material, between remembering and forgetting, between official stories and personal histories – a contest (or to borrow Eisenstein’s words, a conflict) that is at the crux of any notion of ‘representation’. More than how we know, or what we know, the archive is how we map time, and how we escape it. The Meaning of Greatness involves sharing one’s experience and the incidents of political attachment as (collective) forms of distribution. Here, the audience is the fourth dimension: the nuances, the whispers between people, the students, the demonstrators, sitting side by side. Greatness is managed and mismanaged culturally, socially, personally – and so it is more than just time or legacy, it is our interpretation of events, which is never only objective or subjective, it is always multiple. When we open the meaning of greatness to the possibility of social and artistic intervention, to relationships, players, and forces that are often veiled, we can begin to see the gaps, breakdowns, and faltering mechanisms that condition how we know, what we know. One of Jung’s favorite quotes was from Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll, in which the White Queen says to Alice: “It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.”

PEM: And didn’t the king say something like, “Begin at the beginning and go on until you come to the end then stop.”