Neo-Geo Now

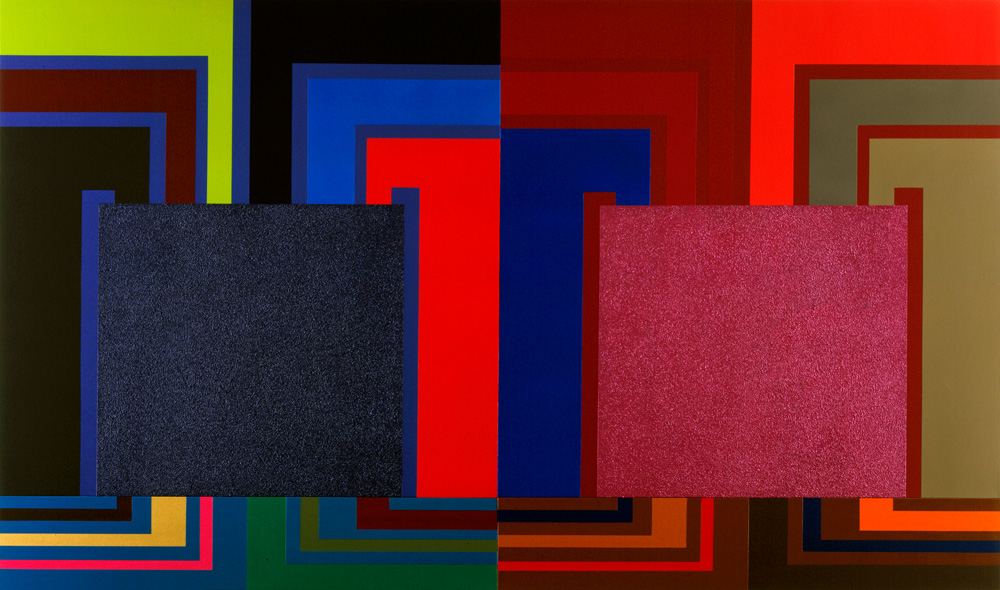

Since the early 1980s Peter Halley has produced paintings adhering to an austere geometric formula, which, despite resembling a pastiche of nonfigurative abstraction in the manner of Josef Albers or Piet Mondriaan, is actually a critique of their mode of archetypal Modernism. In Halley’s postmodern paintings, the early 20th century geometric abstract language of squares and grids – once laden with utopian potential – is inverted. What at first appear to be formal, non-representational compositions are, on closer investigation, revealed to be diagrams evoking prisons, cells, networks, conduits and circuitry. For over thirty years, Halley using commercial materials in vivid hues, has produce paintings that have become ever more complex and multifaceted, their cells and circuits multiplying in a method of obsessive sequential accumulation. In this way, Halley’s paintings can be viewed as diagrams charting the increased regimentation of human movement, activity and perception, a process to which Halley refers to as the “geometricisation of modern life.”

For Halley, the human tendency toward geometric order is visible not only in our constructed environment of cities, factories, schools, prisons, and so forth, but also in “the social schema – the time clock, the chart, the graph, by which bodies and their movements can be measured and categorised.” This fascinating preoccupation with the escalation of geometricisation is also manifest in Halley’s writings, and was given expression in his brilliant essay “The Crisis in Geometry,” first published in 1984. In summer of 2009 I visited Peter Halley in his Chelsea studio. One of my foremost interests in initiating this dialogue was to gain insight into the way in which Halley’s writings function autonomously while simultaneously working to substantiate his methodology as a painter. As a producer of texts that address both his own work and universal theoretical an philosophical issues, Halley may be situated within an influential lineage of artists, including Robert Smithson and Robert Morris, for whom writing constitutes a vital element of artistic practice. With this in mind, I was dismayed to discover during our conversation that Halley has, in his words, “stopped writing due to a lack of critical discussion.(1)”

Halley went on to assure me that he has not “veered away from the set of ideas laid down 20 years ago” when he – along with Jeff Koons and Ashley Bickerton – first attained phenomenal commercial success and critical notoriety as a proponent of the Neo-Geometric Conceptualism (Neo-Geo) ‘movement’. Despite producing dissimilar work, Halley, Koons and Bickerton were unified by their fabrication of glamorous objects employing tactics of appropriation and parody to interrogate the culture of late capitalism. Their slick, polished works demonstrate the near-immediate impact of French Post-Structuralist thought upon the culture of the time.

Though polemical in essence, Neo-Geo art was condemned by several critics who – dazzled by the glossy, luxurious surfaces – were convinced this new wave of artists were complicit with a dominant capitalist model. It seems that as recently as the (infamously capitalist) 1980s there were still those who believed that somehow it might be possible to operate outside the insidious system of capital and commodity. In our discussion, Halley remarked “in those days critics on the left were very quick to critique object-based art as commodity, but this kind of Marxist analysis was irrelevant because by the 1980s even conceptual artworks were selling for high prices (2)”.

Evidently, artists continue to be preoccupied with interrogating the relevance of the art object, a reality manifesting itself not only in individual art practices, but also in the increase in public art institutions favouring artists who facilitate interactivity – via the contrivance of collective encounter – over those who produce autonomous art objects. Halley connects this to “the expression of a new phase of capitalism [in which] corporations gain hold of conceptual property (3) ”and in which “authorial desire” has been subsumed, resulting in the dimunition of the “self conscious vision of the artist’s role (4)”.

As in the work of Warhol, repetition is integral to the meaning of Halley’s paintings. Halley informed me unequivocally that, for him, “criticality is more important than originality.(5) ” Halley’s repetition and accumulation of his emblematic vocabulary highlights the paradox that mass production need not result in the loss of authorial signature or aura, while simultaneously representing the fact that – from the computer chip to the office block – the contemporary world is increasingly disciplined by strict, recurring structures, patterns and codes.

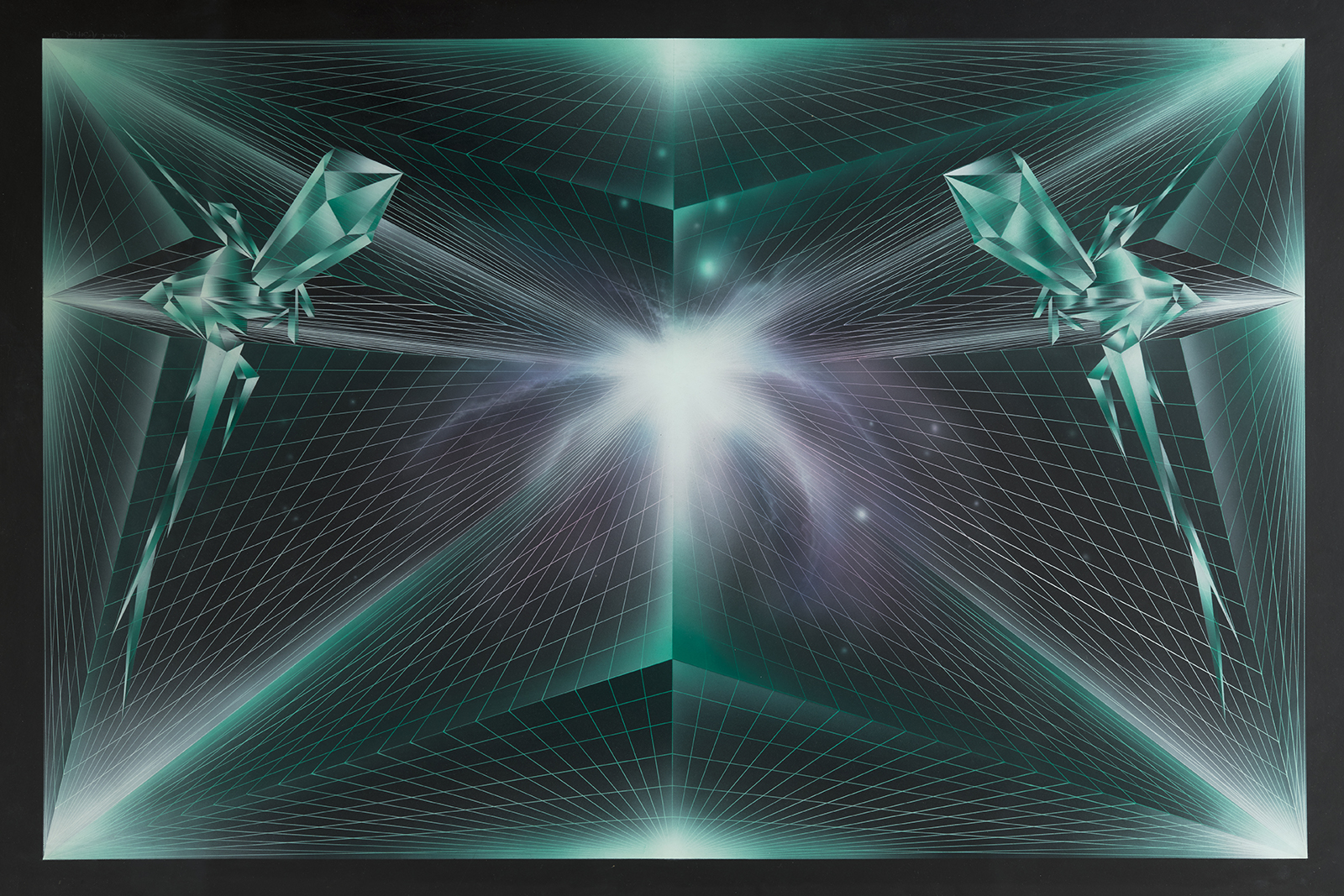

Without depriving us the sensual pleasure of alluring art objects, Peter Halley stands as one of the most intellectually involved cultural producers of our time. In his 1987 essay “Notes on Abstraction” Halley foresees a Foucauldian[6] future in which our “communications, movements, and resources are channeled through digital circuits and become entirely abstract and function as conceptual formal structures.” We now find ourselves moving into this very future at an accelerating rate. Nevertheless, Halley’s paintings are never entirely nihilistic. For in his deployment of rich, seductive solid colours and pure geometric forms Halley proves that abstract painting remains laden with potential.

View Halley’s paintings at: www.peterhalley.com

- Interview with Peter Halley, New York, June 25th 2009.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Pertaining to or illustrative of the theories of French sociologist,philosopher,historian and critic Michel Foucault (1926-1984).