Hard Edged

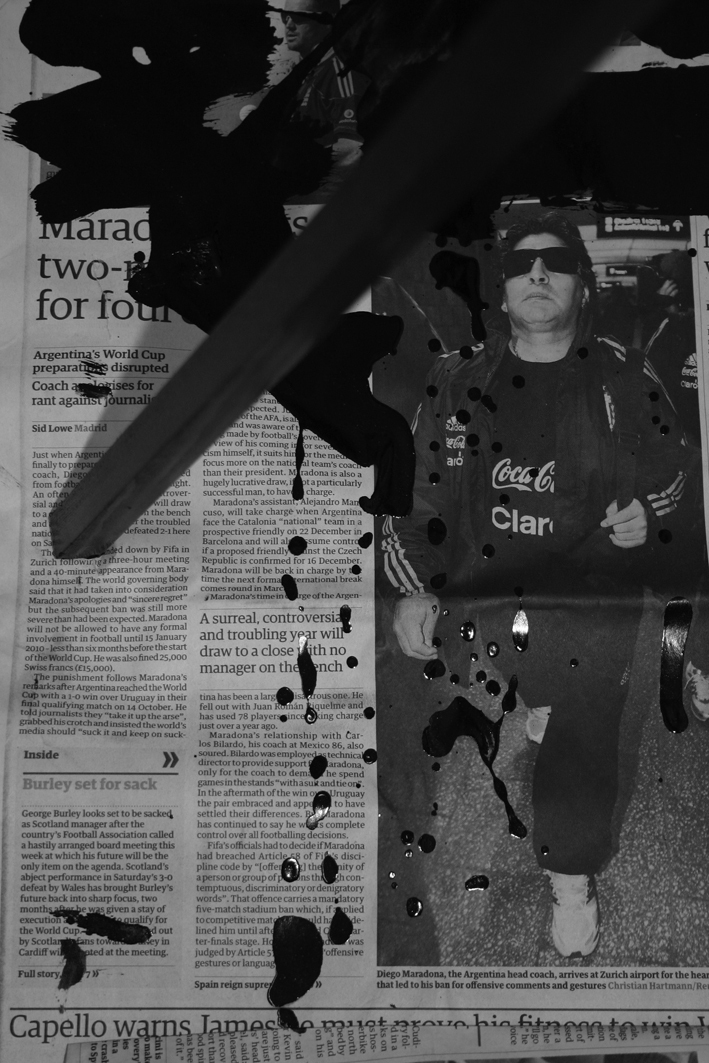

Michael Ashur -and his paintings- had already drifted into obscurity by the time the artist died in Spring of last year. By then, it had been decades since the artist had been included in any exhibitions in Ireland. Opportunities to view this artist’s work are few, but his legacy is worthy of consideration. The vagaries of his career and the circumstances that created them reveal much about the vicissitudes of cultural production in Ireland over the past fifty years. Taking Ashur’s painting as a prism, this essay explores facets of late 20th century Irish Art. In so doing, this text also exposes some of the persistent perils facing artists on this island.

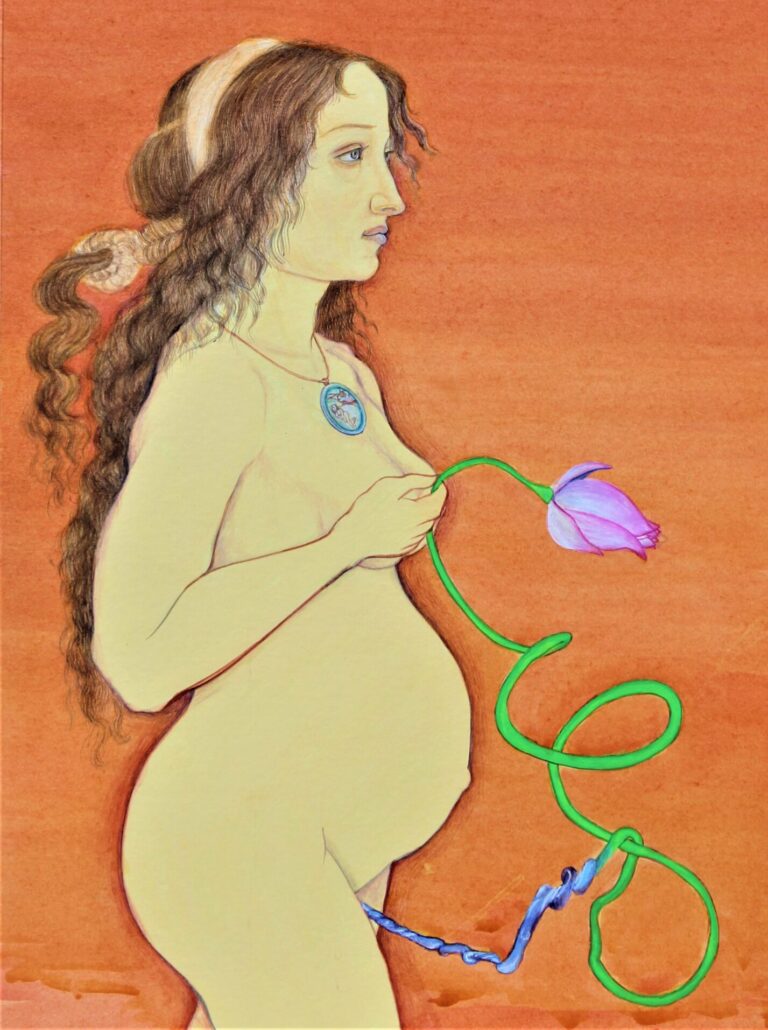

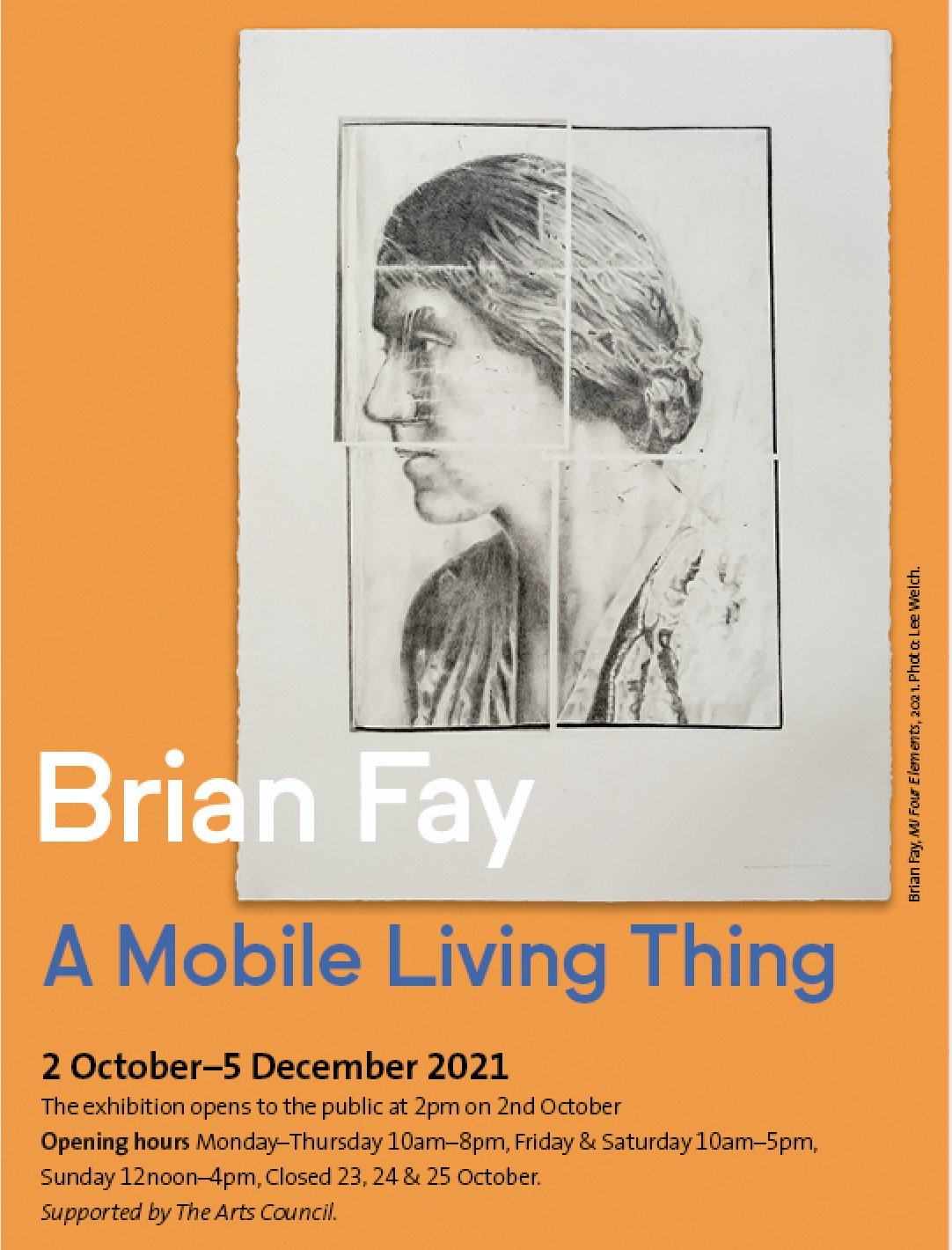

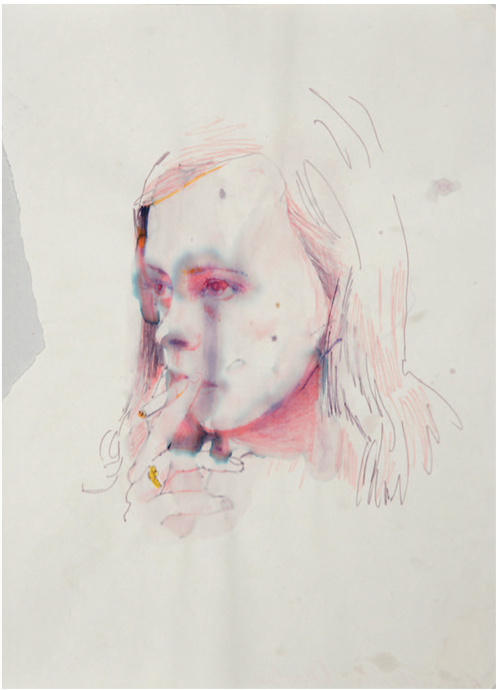

Since this essay has been commissioned for inclusion in the annual RHA exhibition publication, we begin there, as a means of giving some necessary context. For almost two centuries, this annual cultural event has provided a snapshot of work made by a cohort of artists in Ireland. While there is much variety to what one sees here, painting is the mainstay. Within this, a distinguishing feature of this perennial show is the eclecticism of what is on display. One is just as likely to encounter a painting evoking Italian Mannerism as Neo-Expressionism. Today, figurative painting continues to be in vogue and a younger generation of artists are making images that are a testament to a renaissance of portraiture. This is a reflection of how styles and signifiers are used freely in contemporary art, no longer rooted to doctrinal positions.

This wasn’t always the case. The rejection of paintings by several artists from annual RHA exhibitions in the early 1940s represents how, even at that late stage, the venerable academy eschewed even moderately progressive modes of painting. The exclusion of pieces by Louis le Brocquy, Nano Reid, and others, became a cause célèbre that resulted in outrage from certain quarters, as exemplified by Mainie Jellett’s statement that the “the RHA would die of senile decay”[i] if it continued to “shut its doors to life”,[ii] by which she meant non-representational painting. Evidently, artworks today do not elicit the same level of controversy or debate as they did in the last century.

The aforementioned demonstrates how academic art—or, at least, figurative art—held sway in Ireland and was often implicitly charged with the mission of representing national identity in flux. While there are notable exceptions, art was late to embrace progressive approaches. Visual art was a marginal artform in Ireland in the early twentieth century. The constellation of aesthetic movements and stylistic missions that flourished in quick succession across the last century did not occur in Ireland, as they did elsewhere.

It was only in the mid-1960s and the early 1970s that the situation changed. This was a watershed moment for the visual arts in Ireland, which witnessed a substantial shift in perspective. Public exhibitions of International Art were a vital catalyst in changing the cultural milieu. The impact made by the Rosc has been explored in several recent studies,[iii] but other major exhibitions—such as USA Art Now at the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin (1964)—caught the imagination of artists and the general public. Offering audiences the opportunity to view Pop art, colour field painting, and hard edge abstraction, these initiatives also increased audiences for the visual arts.

A strain of tasteful formalism proliferated in Irish visual art from the mid-1960s onwards. Elegant, decorative abstraction, epitomised by Patrick Scott, Cecil King, Alexandra Wejchert etc al reflected international developments and appealed to the sensibilities of a small but influential coterie on the island. The plaster works of Maria Simonds-Gooding from the late 1960s stand out as testament to the fact that artists active on the island were making work that resonated with Post-Minimalism. For a considerable period of time Architect Michael Scott and art collector Basil Goulding were arbiters of taste whose dominant influence is alluded to in an article in Magill magazine from 1979 in which it is stated that these two individuals “effectively held in their hands discretion over the future direction of careers and of taste”.[iv]

Unparalleled power was wielded by Fr Donal O’Sullivan, director of the Arts Council between 1960 and 1973. O’Sullivan’s proclivity for artworks that emulated the ‘universal language’ but which were also compatible with Jesuitical principles can be seen in many acquisitions made at this time by the Council. This period in the 1960s saw a small number of commercial galleries successfully establish an art market in Dublin, a detail that I will touch upon later.

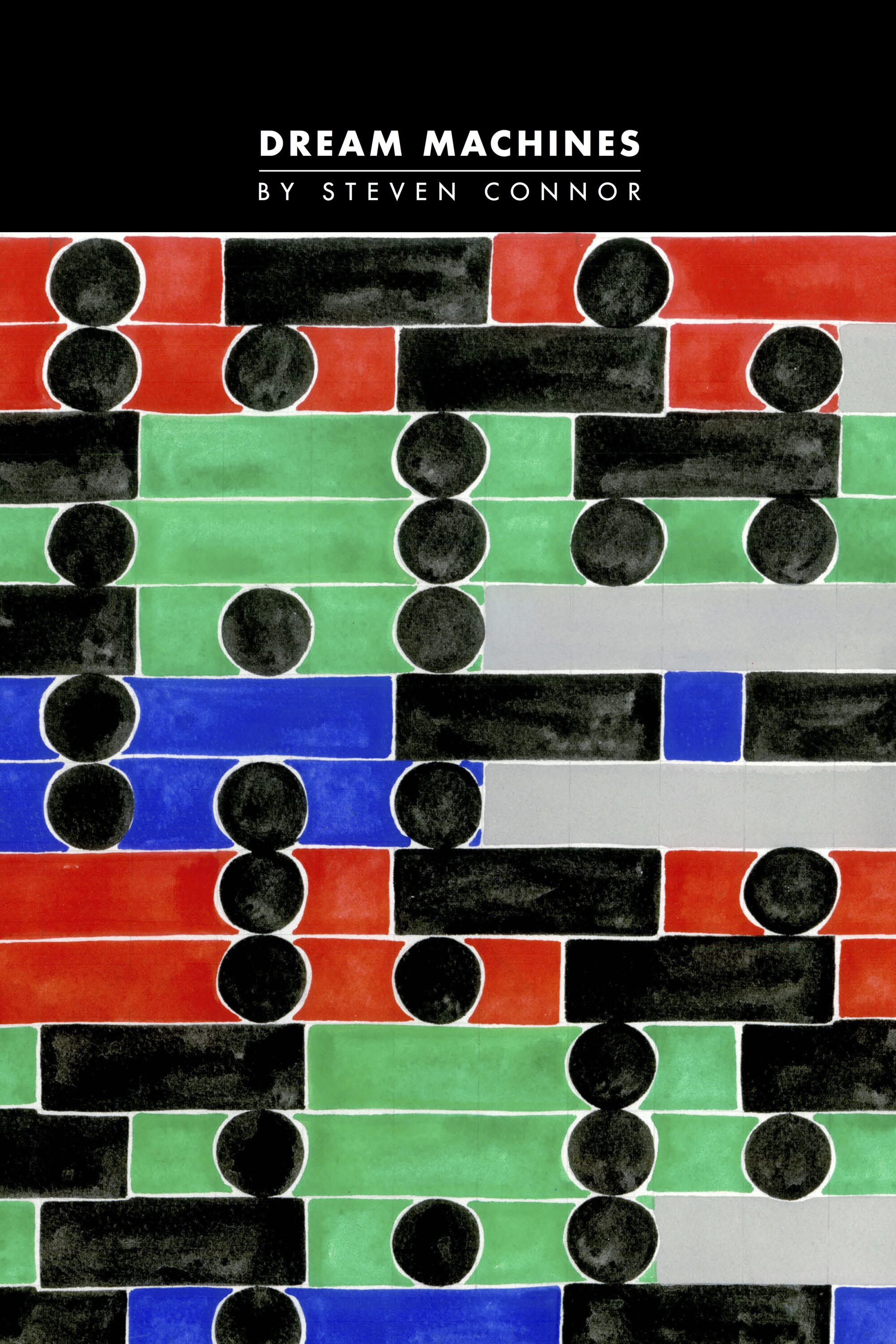

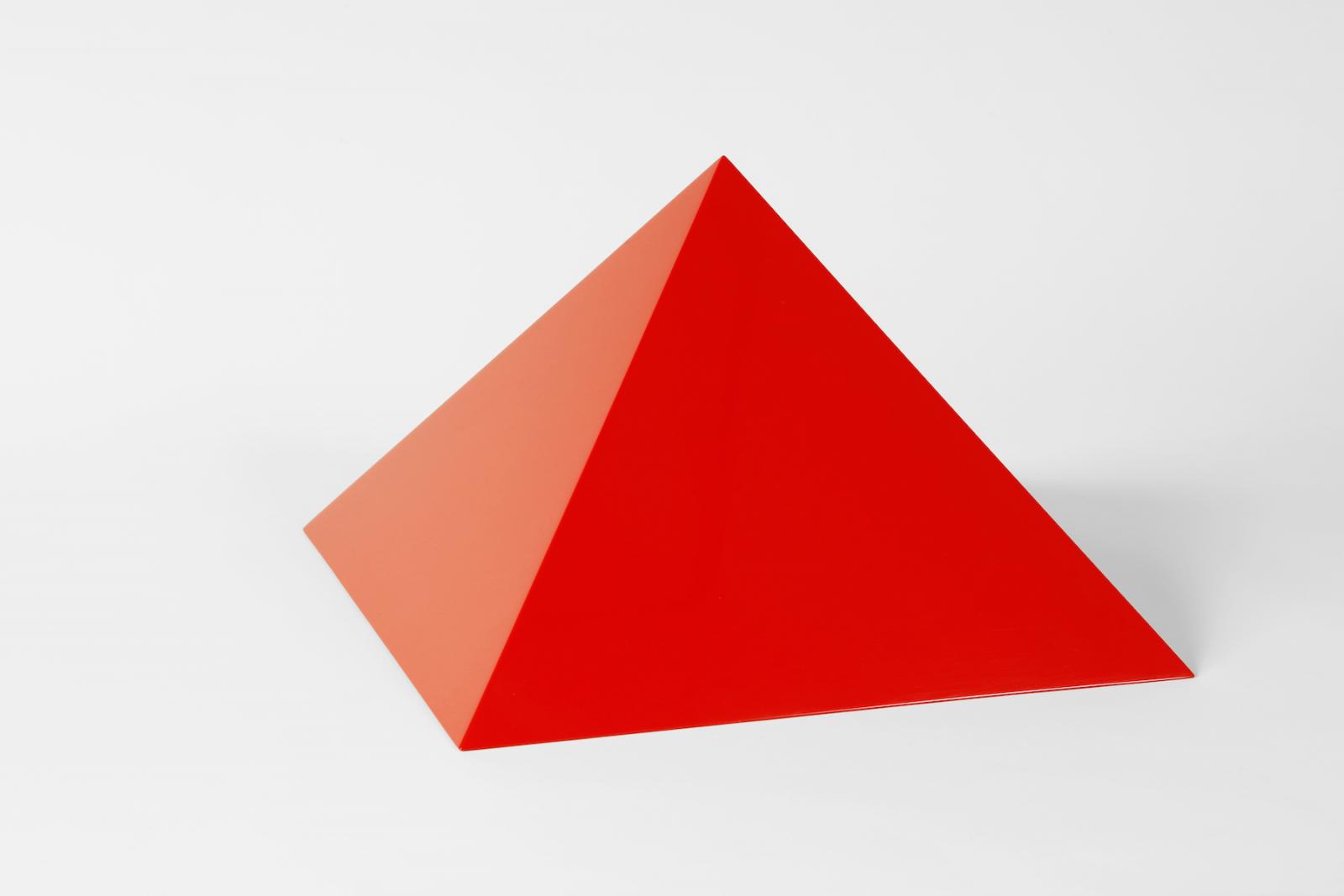

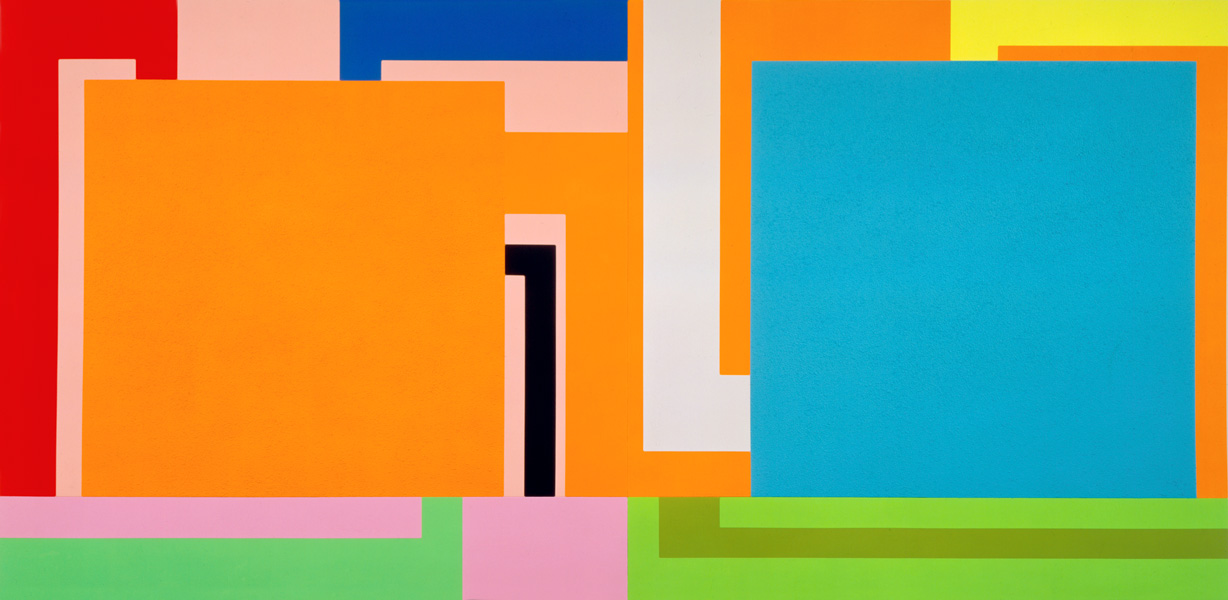

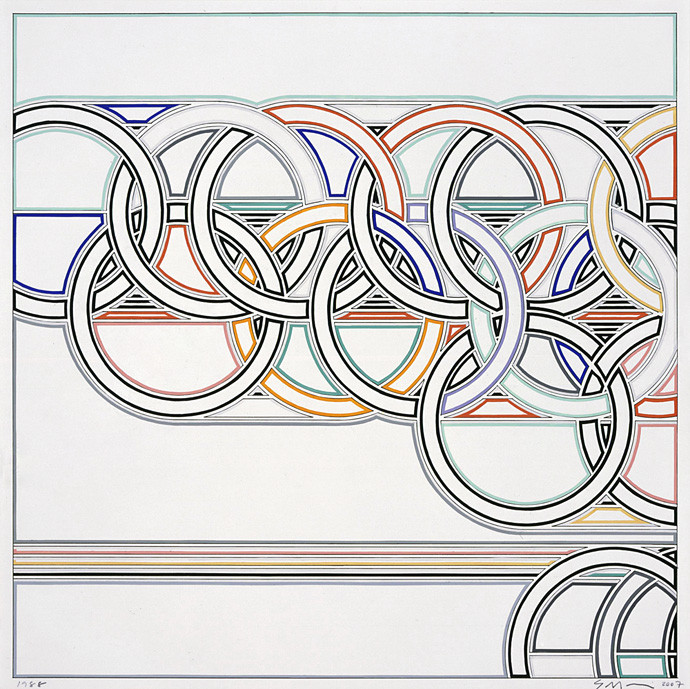

A number of artists who emerged during this period and made work reflecting the prevailing trends remain active today, albeit making very different art. Martin Gale points out how the early to mid-1970s saw a surge of artists, including himself, producing hard edge painting.[v] To some extent this was a reflection of what was in vogue but also a response to the perceived domestic demand for such work at the time. Gale’s point is illustrated by numerous examples. Michael Farrell was probably the first to embrace and propagate this mode of painting. Seán Scully and Brian Henderson both made work in the early 1970s that combined hard edge approaches but by the 1980s were making work that was more expressionistic and ultimately responsive to the zeitgeist.

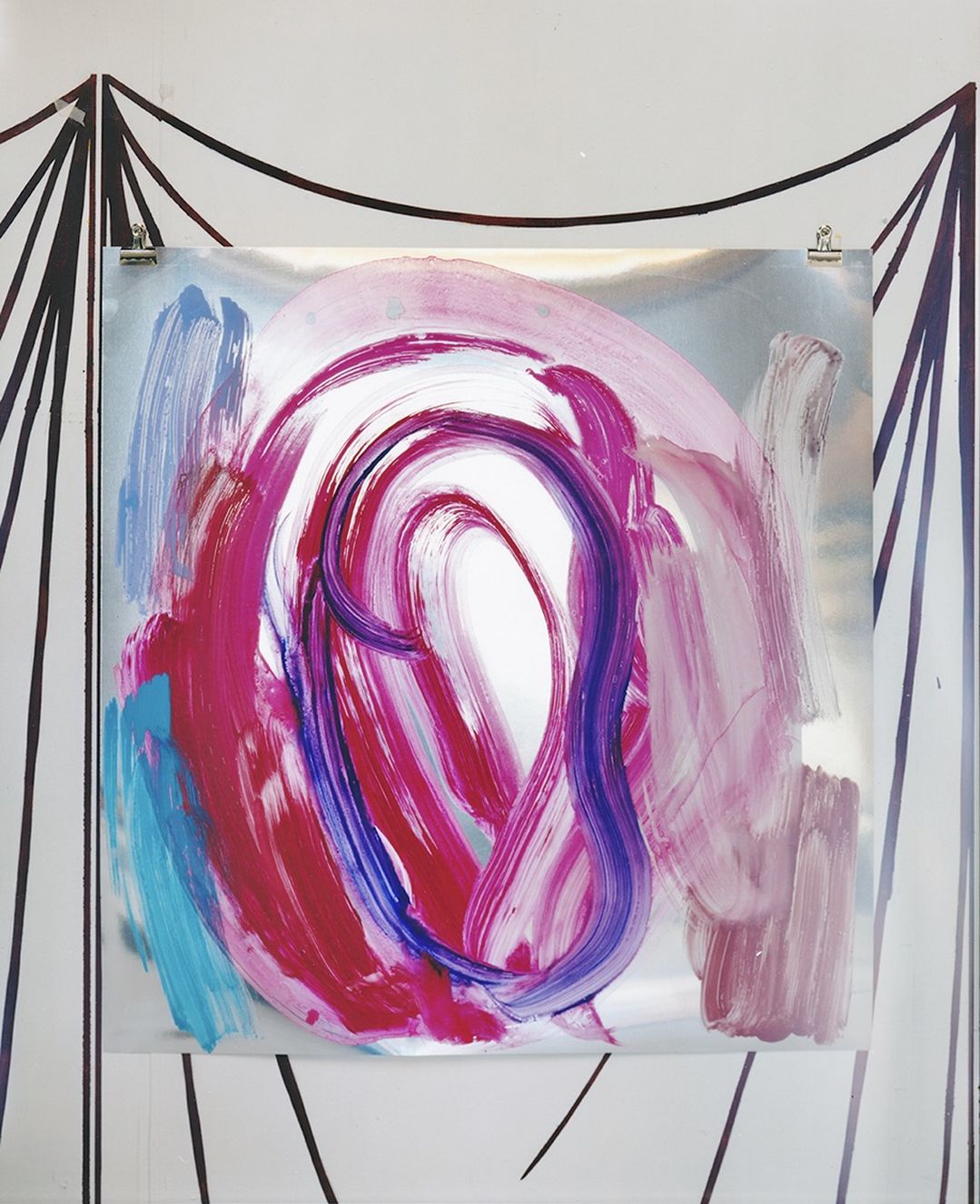

Another artist who came to the fore in the early 1970s, and who initially enjoyed considerable success, was Michael Ashur. Although he is frequently compared to Henderson he remained doggedly committed to developing the visual language he had established. Ashur’s case highlights the potential fate of an artist who originates a particular novel aesthetic and how that can ultimately lead to both great recognition but also eventual obscurity. The arc of his career demonstrates the pitfalls of becoming too popular too soon; and saturating a particular locale whilst remaining steadfastly committed to a singular vision.

Some biographical detail is useful. Born in 1950 and raised in Drumcondra, Dublin, the artist then known as Michael Byrne commenced his studies at the National College of Art and Design in the late 1960s. This was a notably turbulent phase at NCAD, as the countercultural climate that flourished elsewhere was transmitted through the ether to art students. Upon leaving NCAD, Byrne assumed the pseudonym Ashur, after a Babylonian sky god[vi].

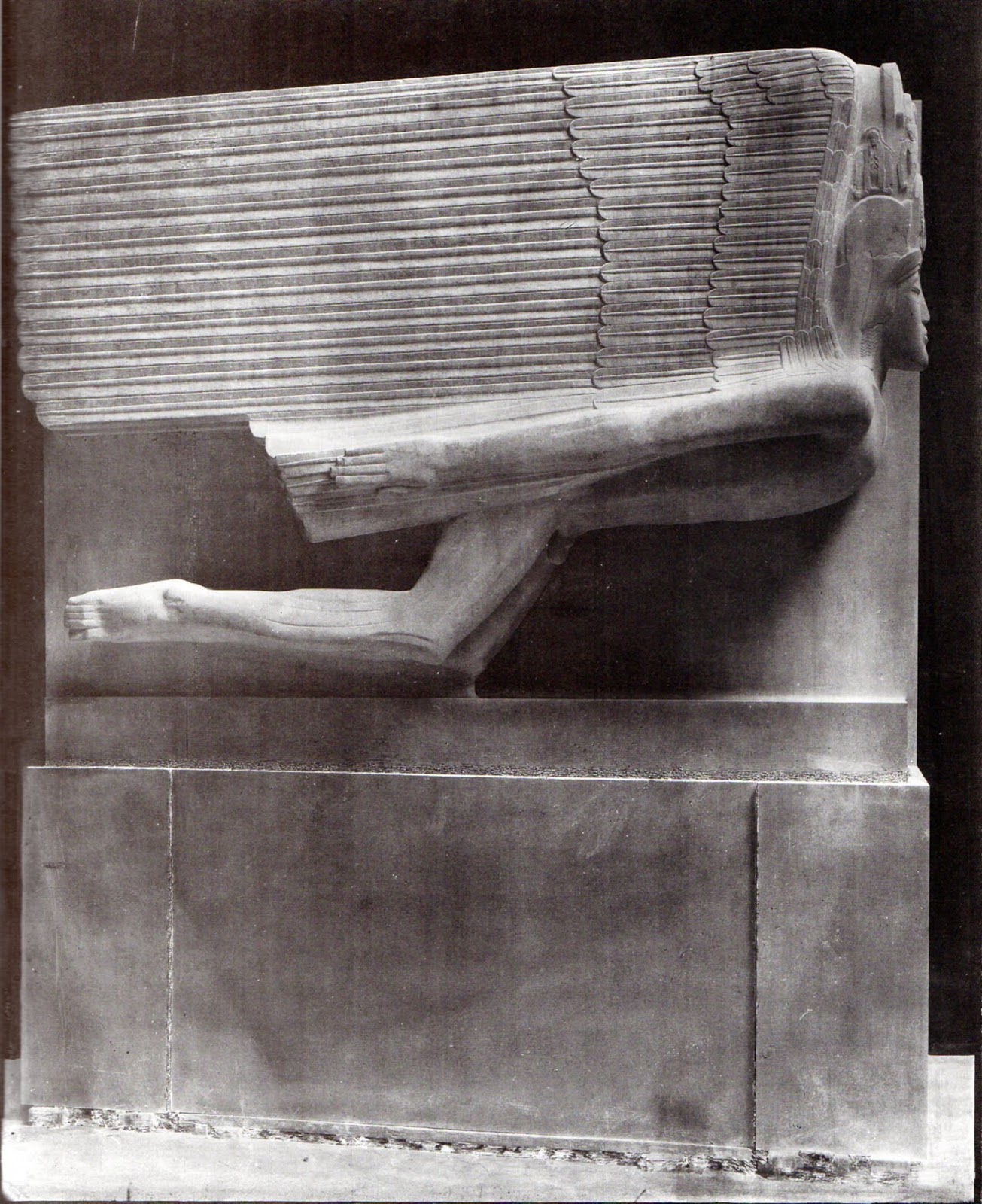

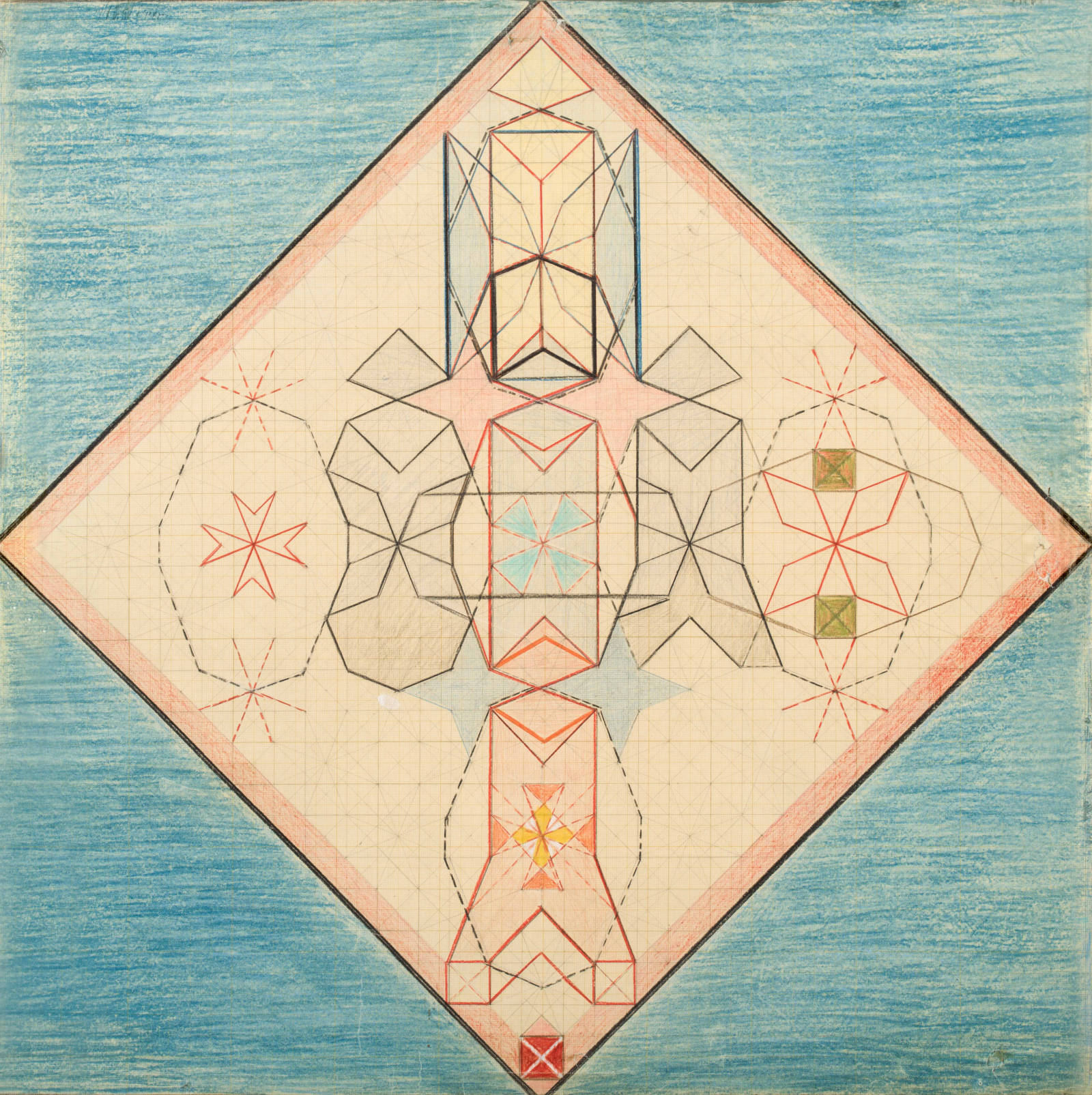

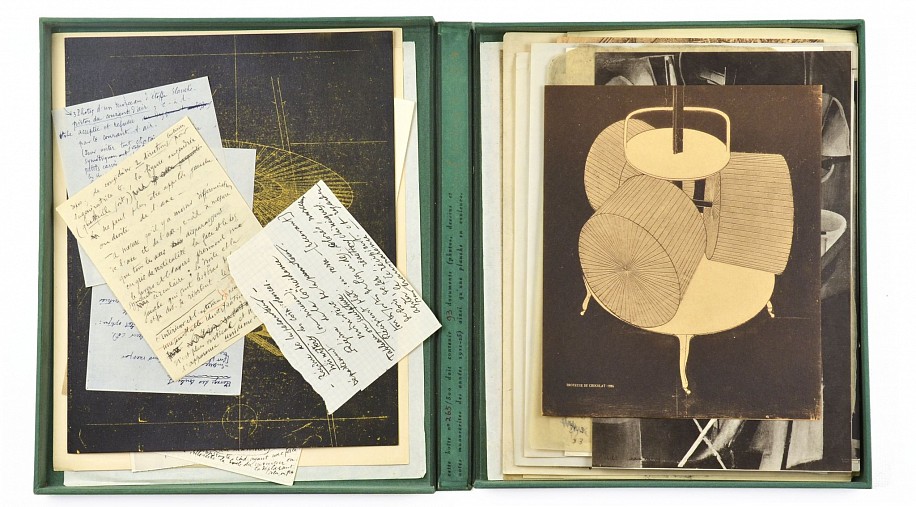

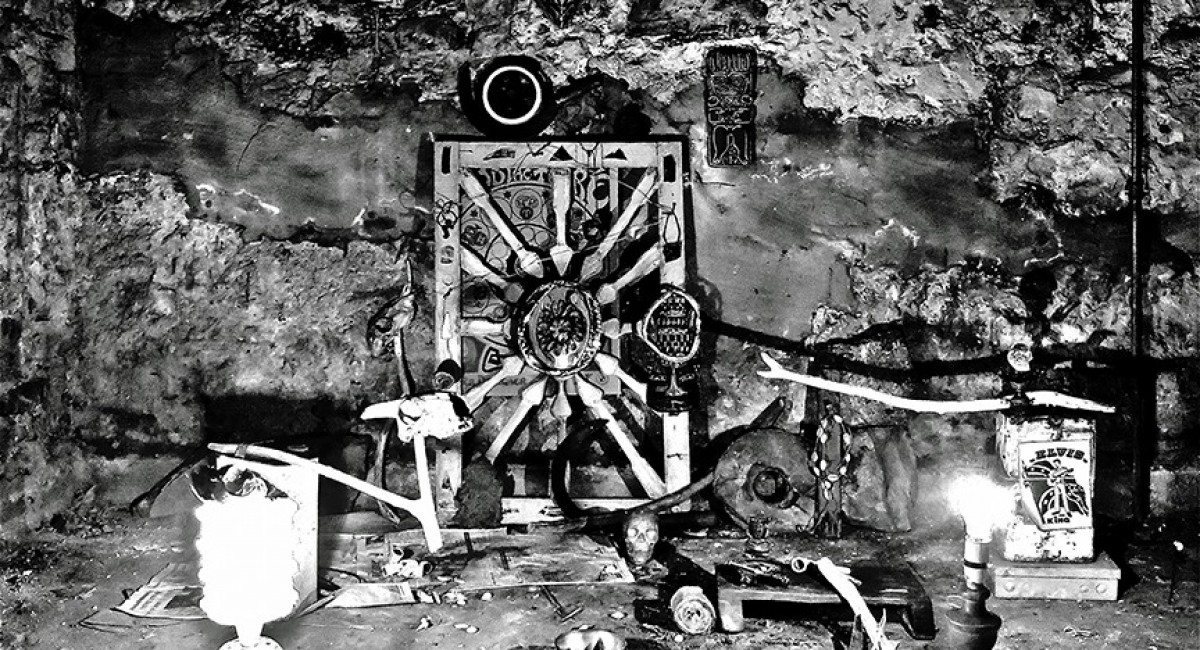

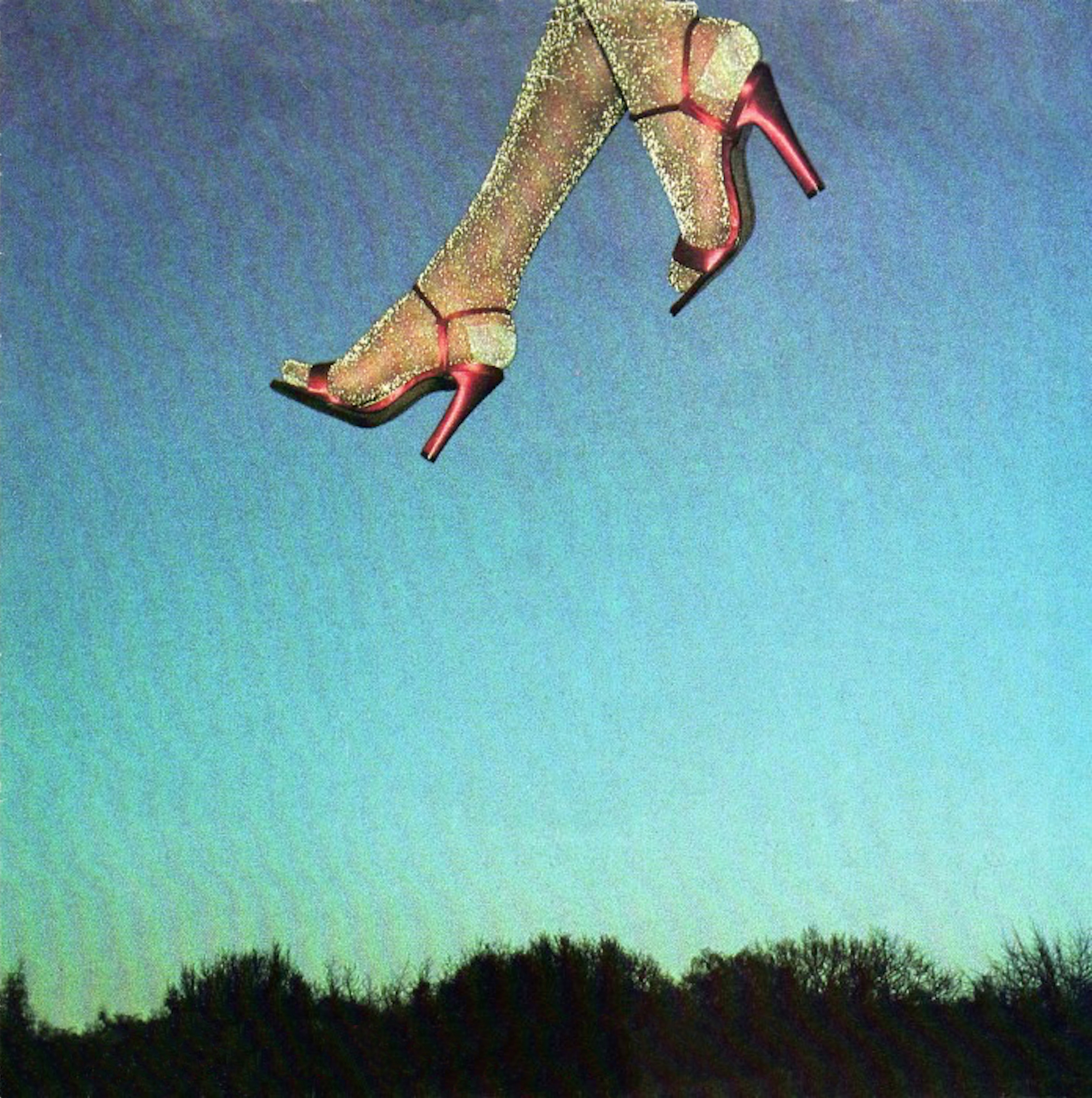

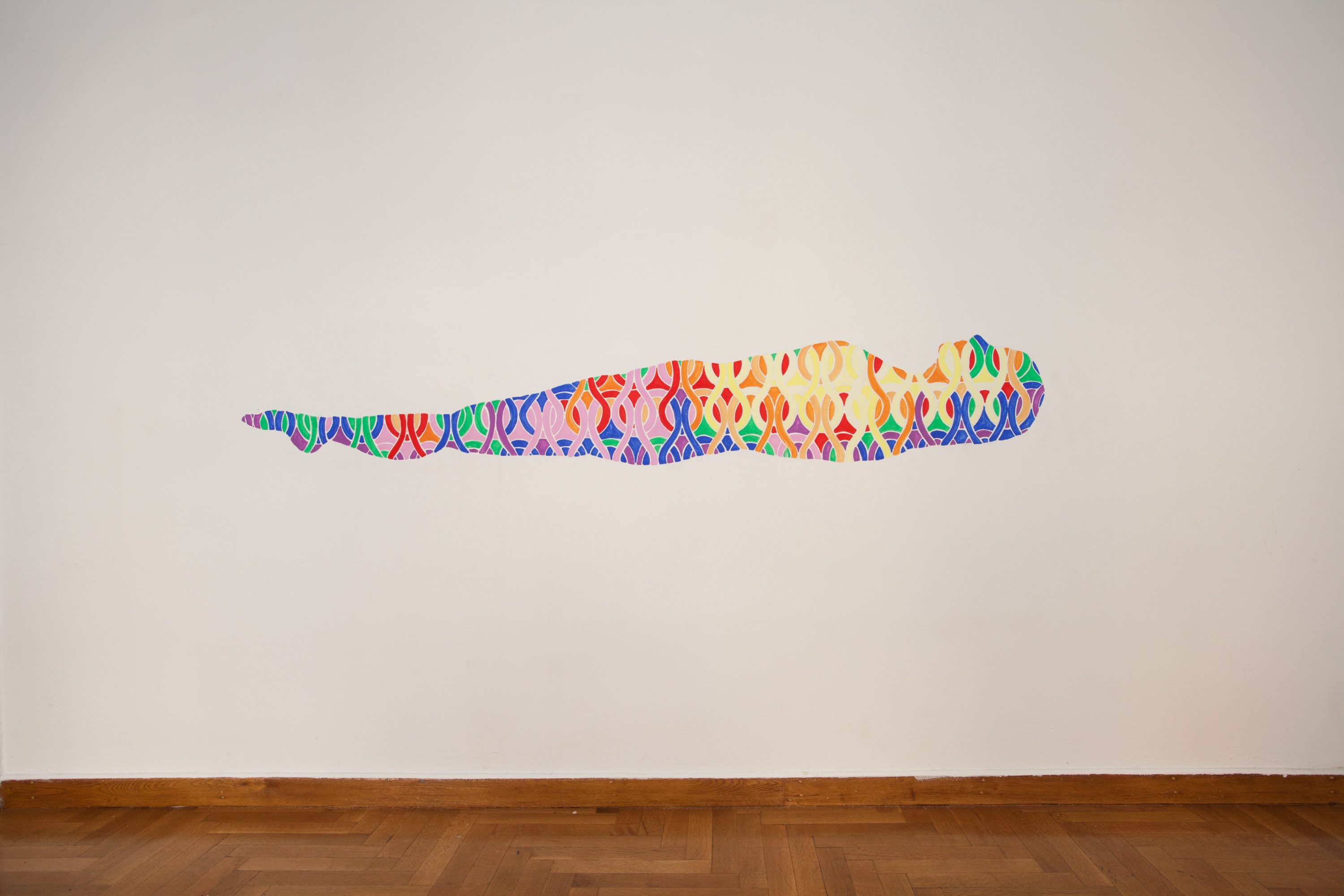

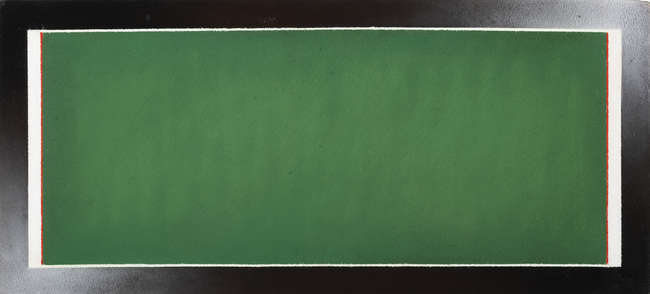

Ashur’s early work shows an awareness of international painting and he is perhaps the only Irish representative of the shaped canvas movement, proponents of which he would have seen at the Rosc exhibitions.[vii] Encountering works by Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely, at an exhibition of Op art curated by Fr Cyril Barrett at the Hendriks Gallery, Dublin, was a formative experience for the artist. The Hendriks gallery—which would later represent Ashur—was important for introducing international contemporary art to audiences and presented significant exhibitions of Pop Art and Arte Povera. Ashur would go on to have several successful one-man exhibitions at the gallery and they would represent him for almost two decades.

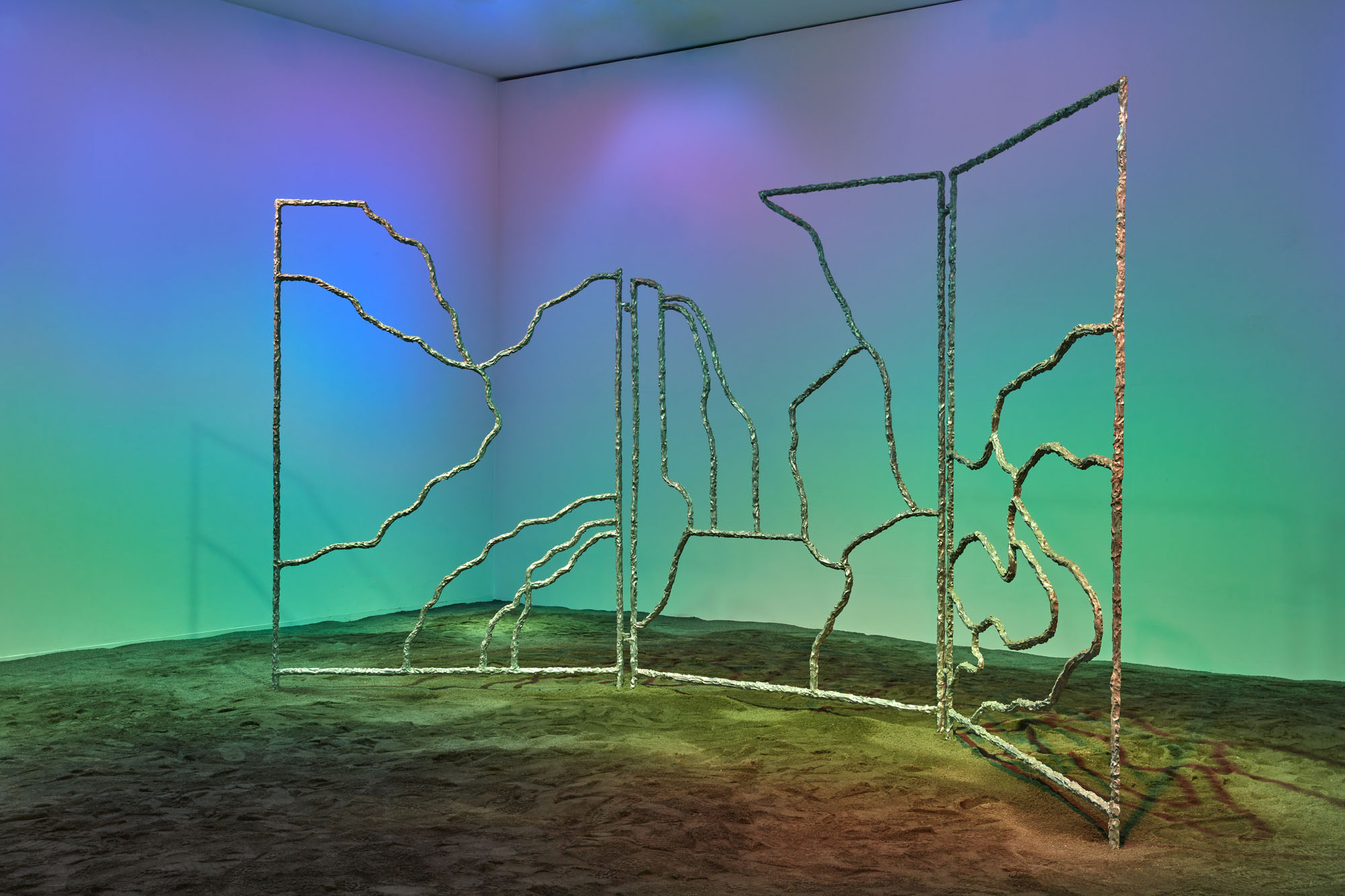

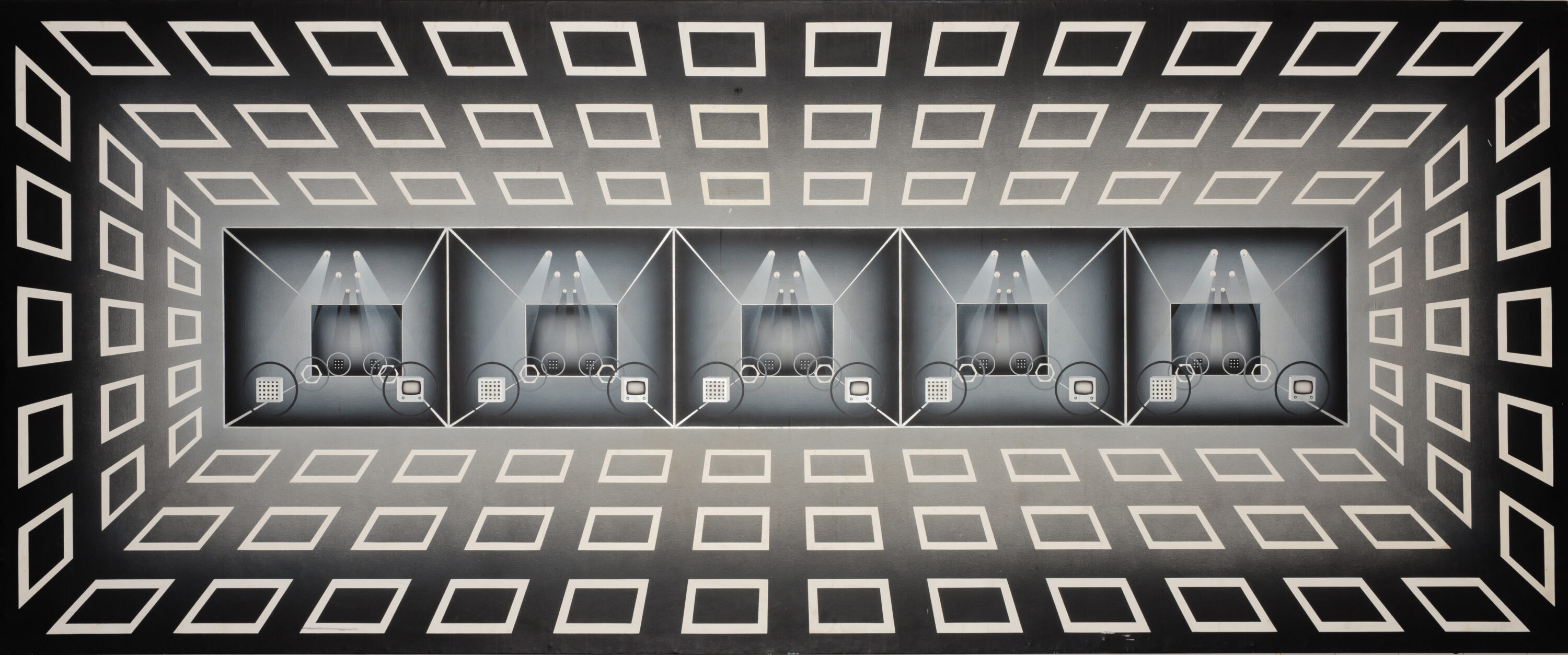

It is notable that many of the acquisitions of his work in the 1970s and early’80s were by organisations with large premises, for example, Telecom Éireann and RTÉ possessed monumental works of his which decorated their office headquarters. Such is the scale of some of Ashur’s work that it might be described as campus or foyer art, essentially, (cosmic) decor for the newly built cavernous environments. The wave of construction in this period also led to numerous new commissions, the legacy of which is now particularly evident in the presence of momentously large sculptures. This is evidenced, in particular, by the sculptures of Brian King at University College Galway; Michael Bulfin and John Burke in Miesian Plaza (formerly known as the Bank of Ireland Headquarters), Dublin; Alexandra Wejchert at Maynooth University, Co. Kildare; and Gerda Frömel at the cigarette factory outside Dundalk, Co. Louth.

Christina Kennedy touches upon this subject in her essay on the David Hendriks Gallery in IMMA Magazine (2014), when she notes that: “With improving economic conditions from the mid 1960s and the emergence of a corporate sector there was interest in larger artworks to complement the minimalist lines and unadorned surfaces of the steel, glass and concrete ‘Mies van der Rohe inspired’ buildings designed by leading architects Ronnie Tallon and Robin Walker of Scott Tallon Walker.”[viii]

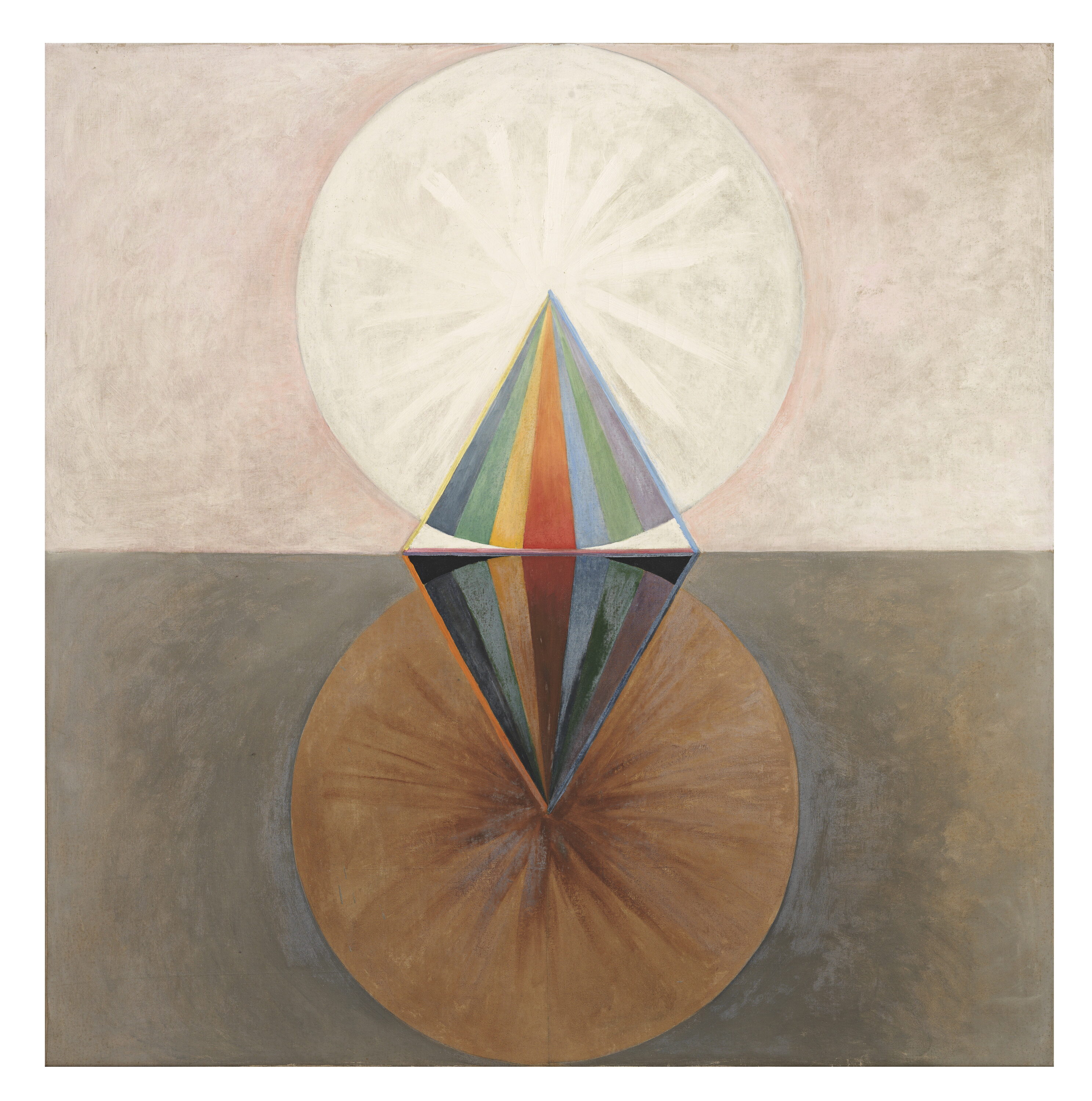

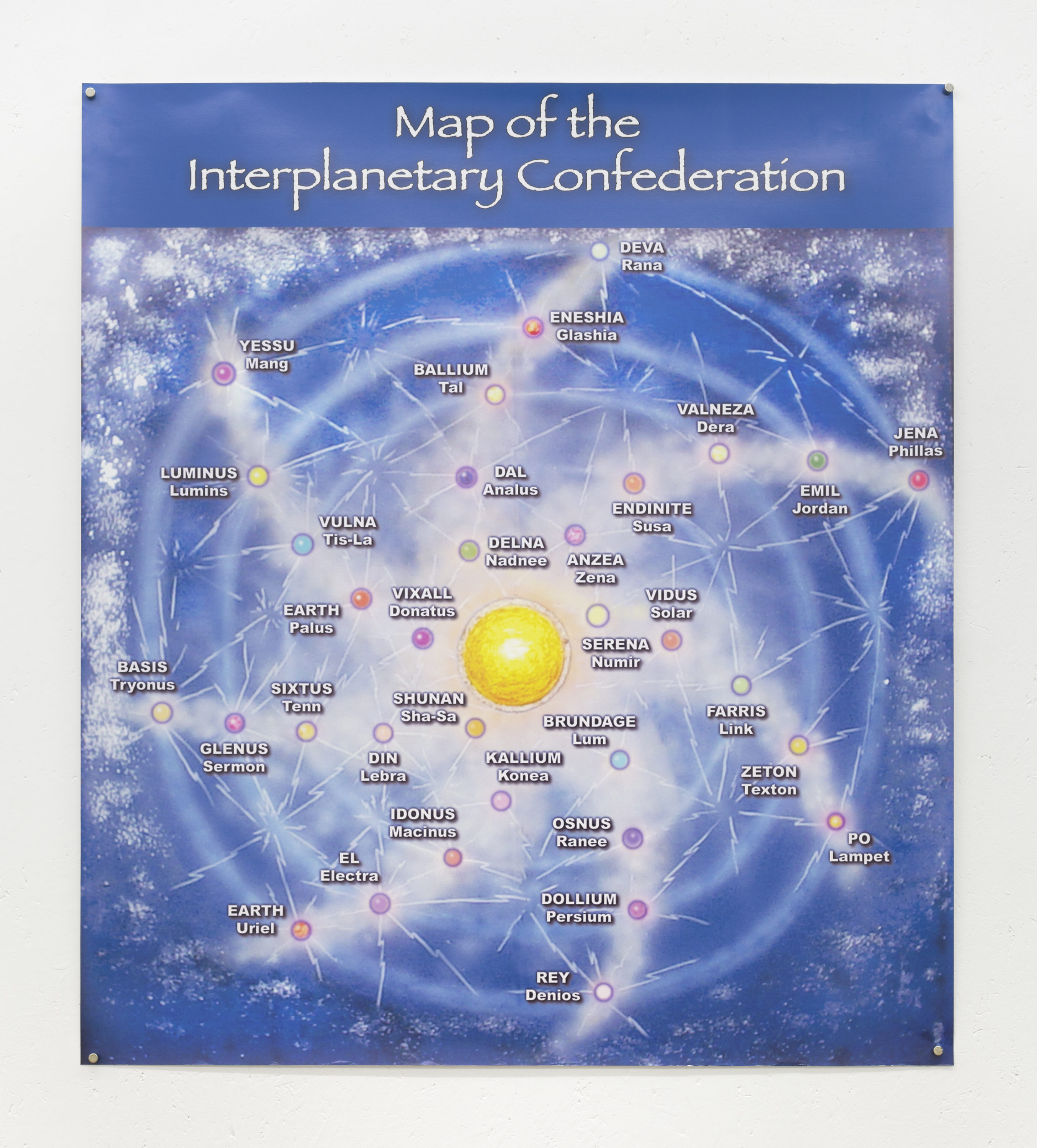

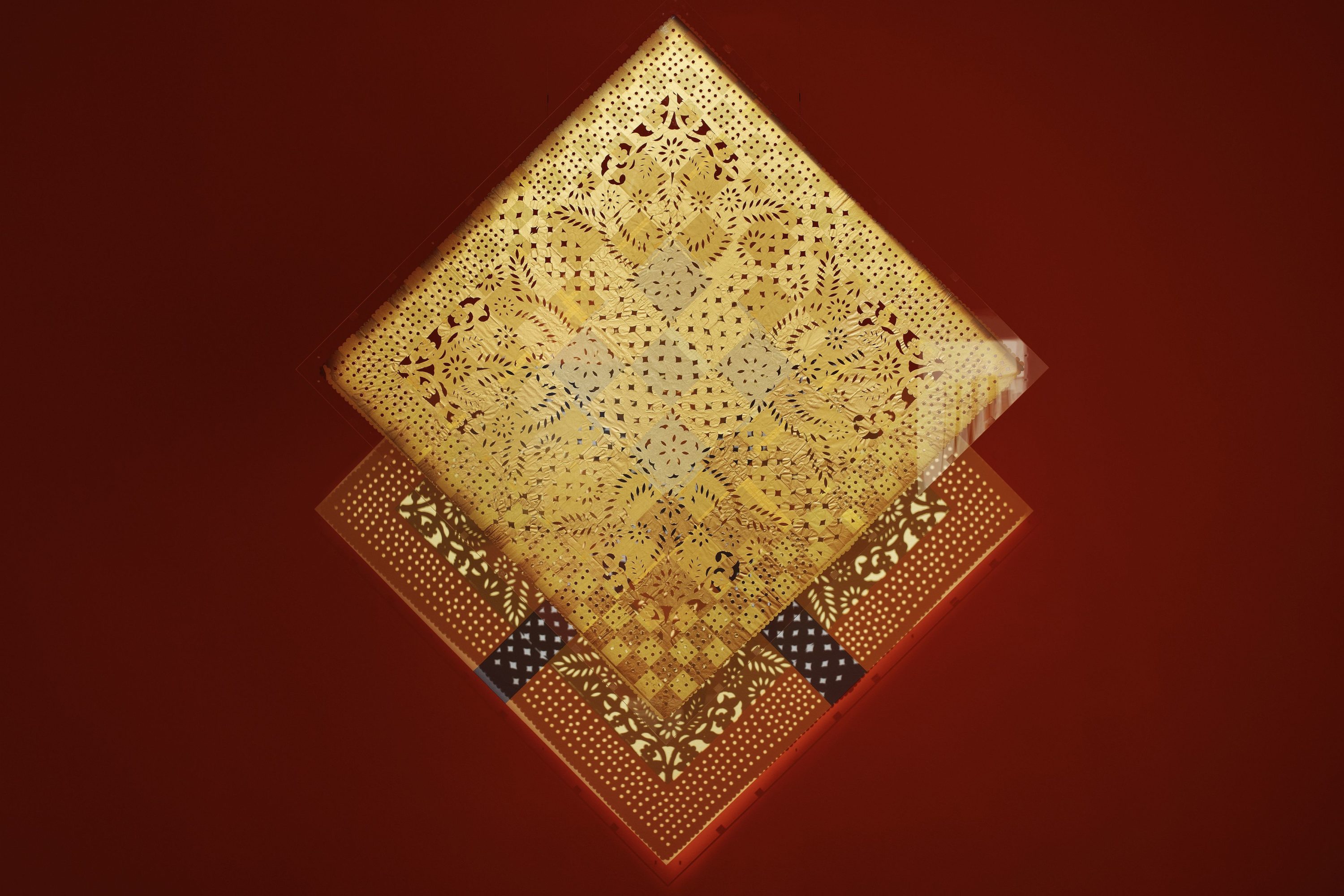

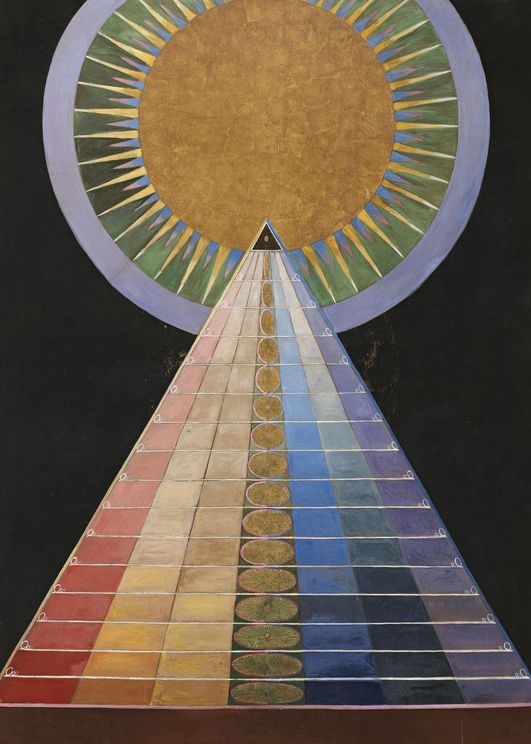

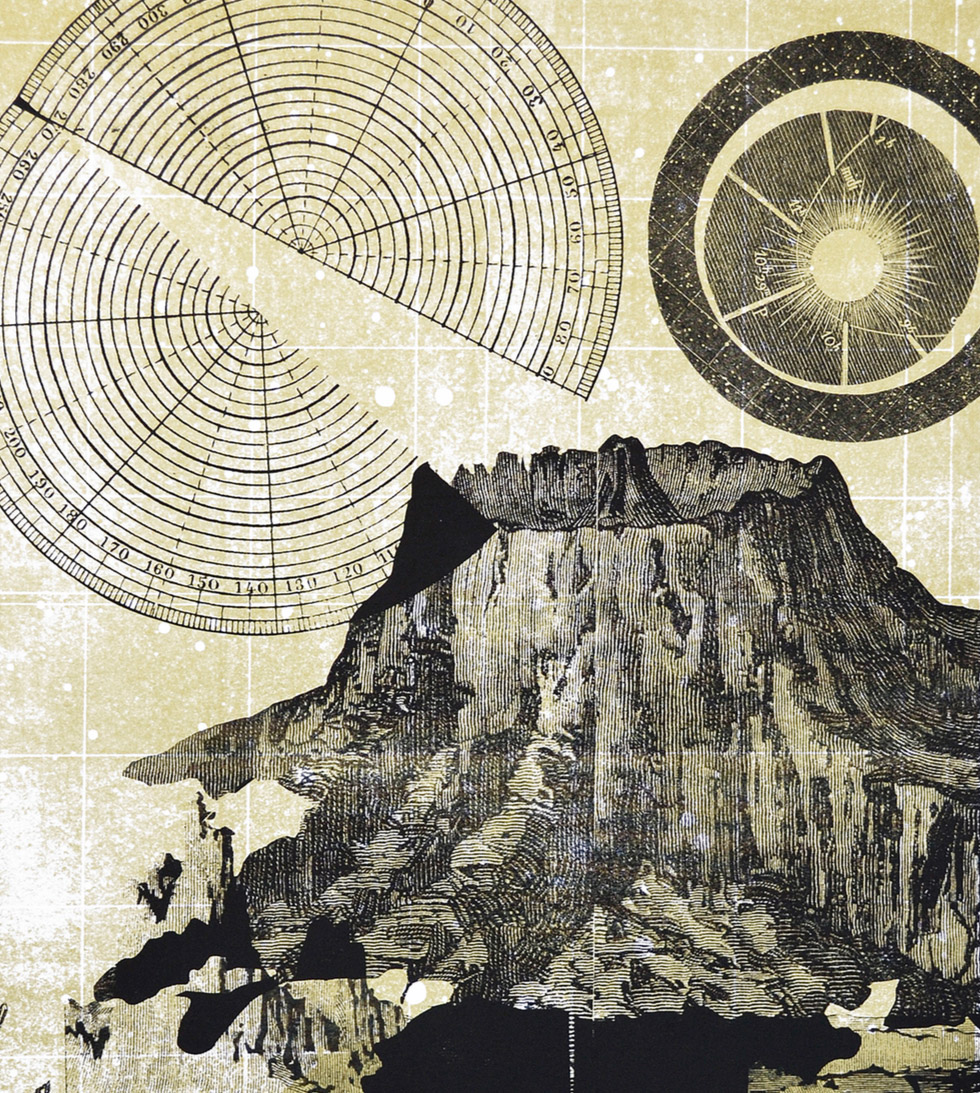

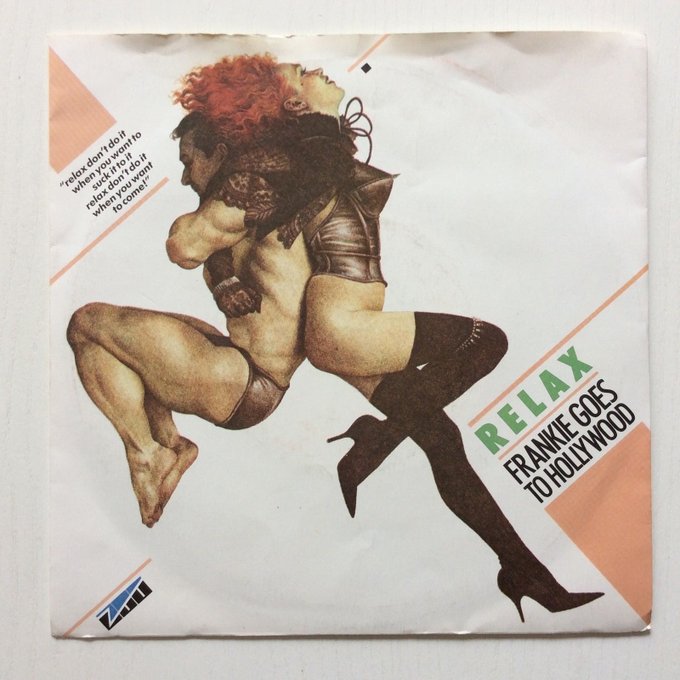

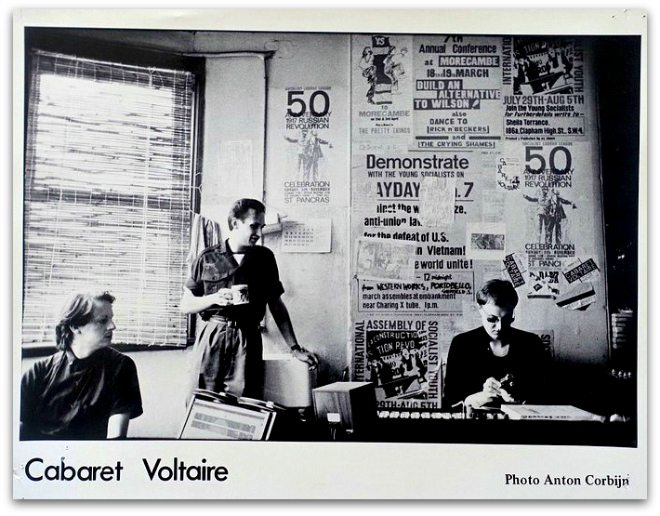

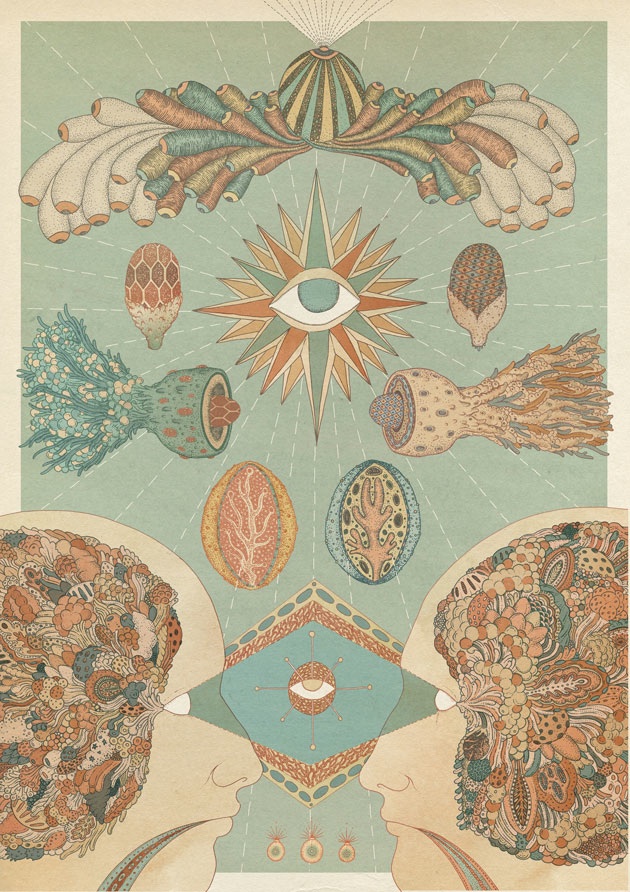

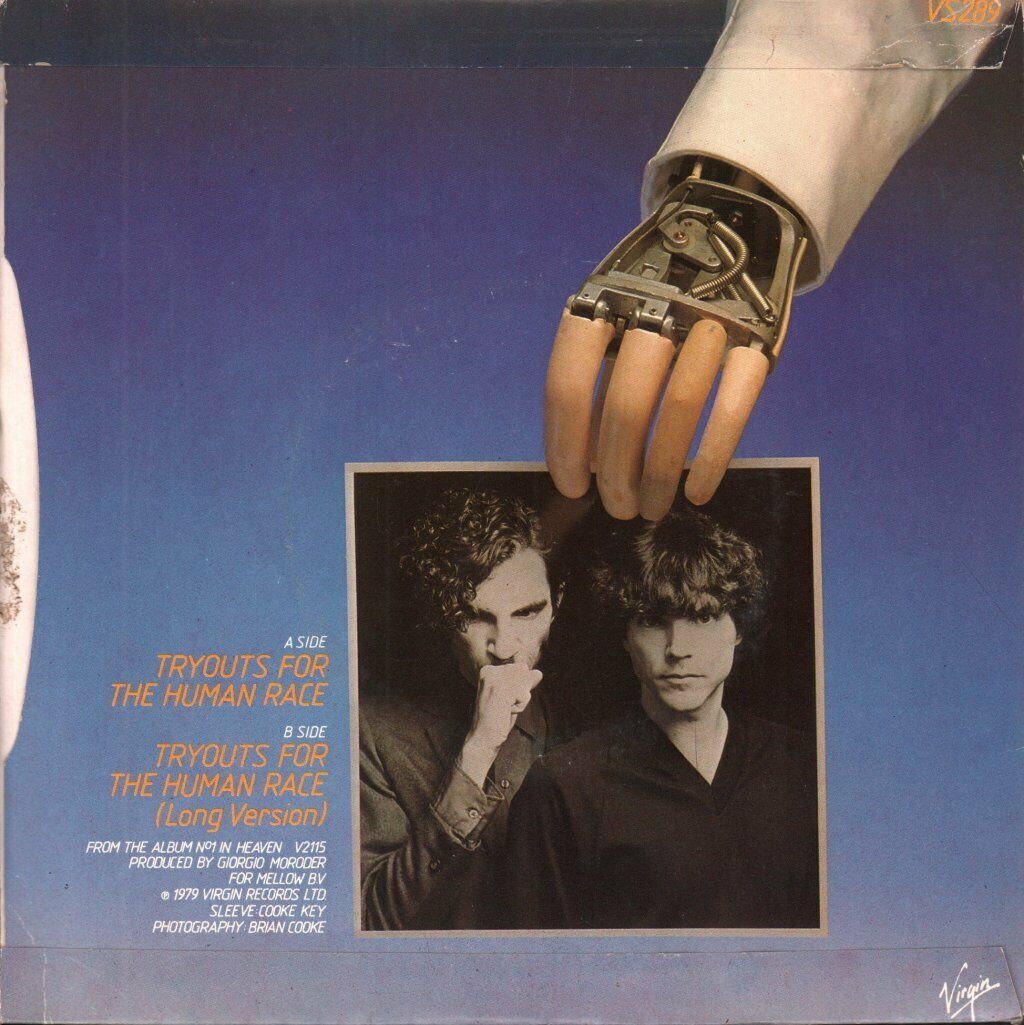

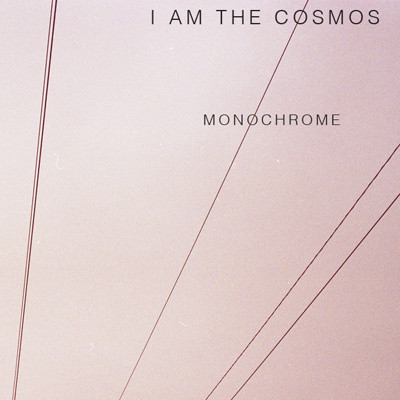

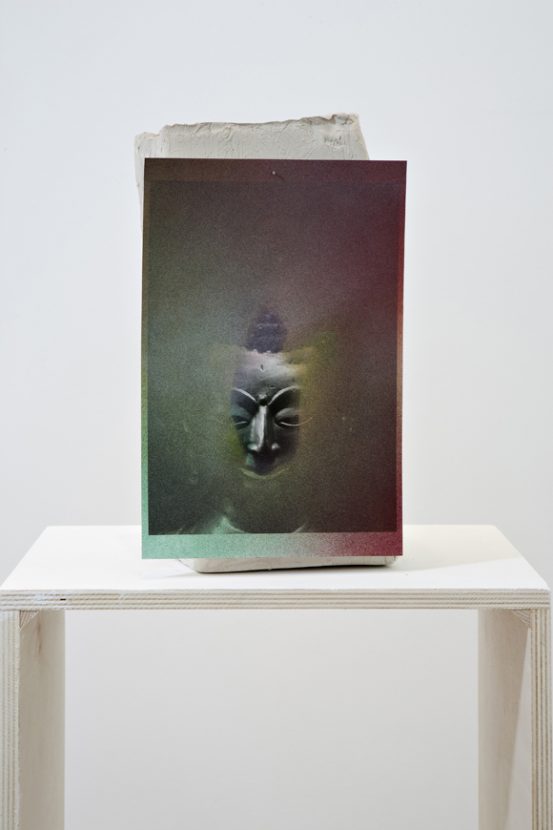

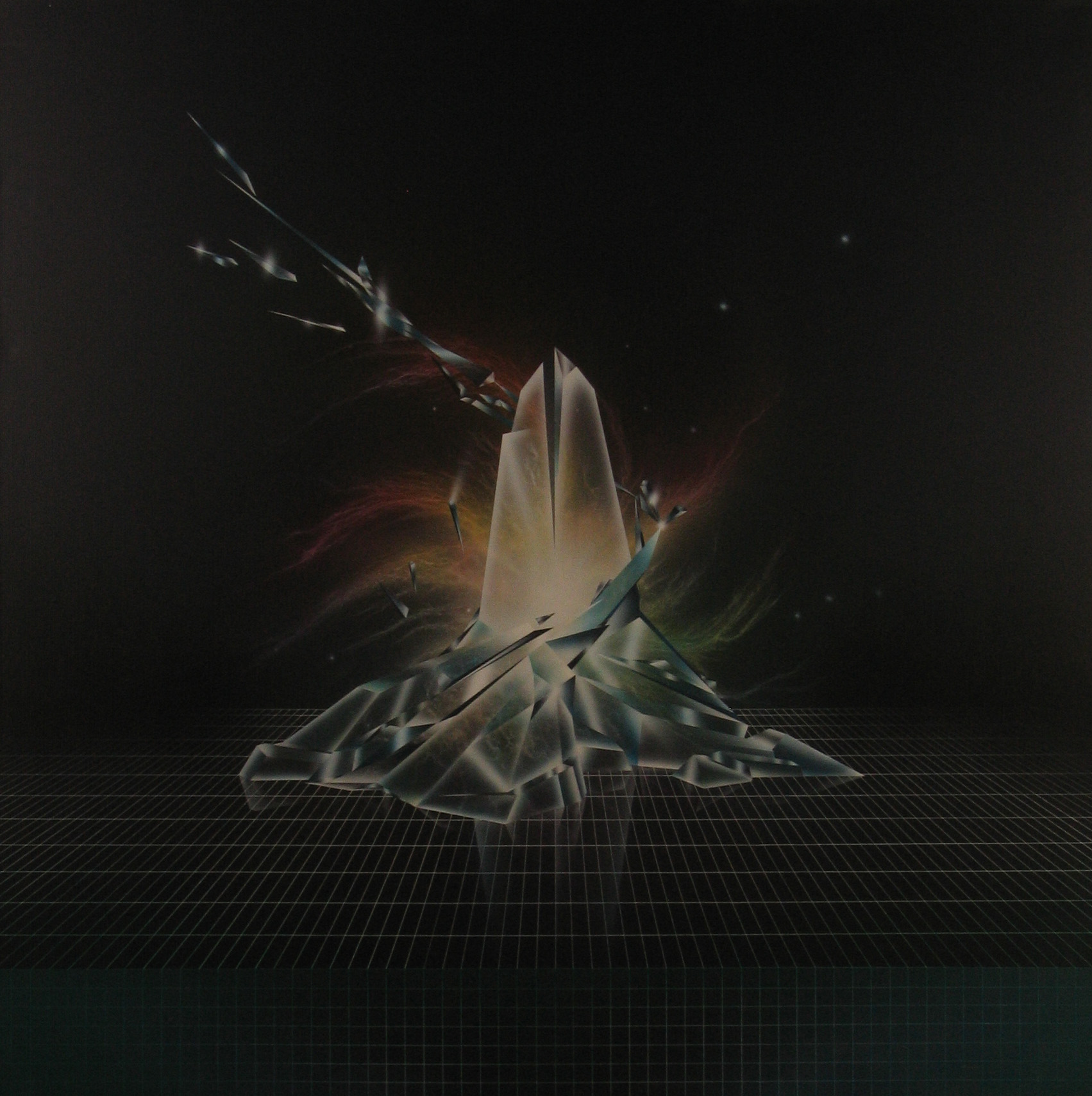

However, Ashur’s initial success cannot be explained solely by the fact that his art functioned as corporate décor. The visual novelty of his work and its capacity to capture the eye and imagination was central to his initial success[ix] . With their luminous hues and angular crystalline compositions, these pictures appear backlit and prefigure much of what we see today on digital screens. But what makes this artist distinctive and idiosyncratic are the non-art influences that shaped his work. Ashur came of age in the late 1960s; a period suffused with science fiction and space exploration. Technological progress and pop culture fused; Stanley Kubrick’s classic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, was released in 1968, the year before the lunar landings. The era was also fundamentally shaped by aesthetics that evoked altered states of consciousness: fantastical and galactic imagery, often containing optical and perceptual illusions.

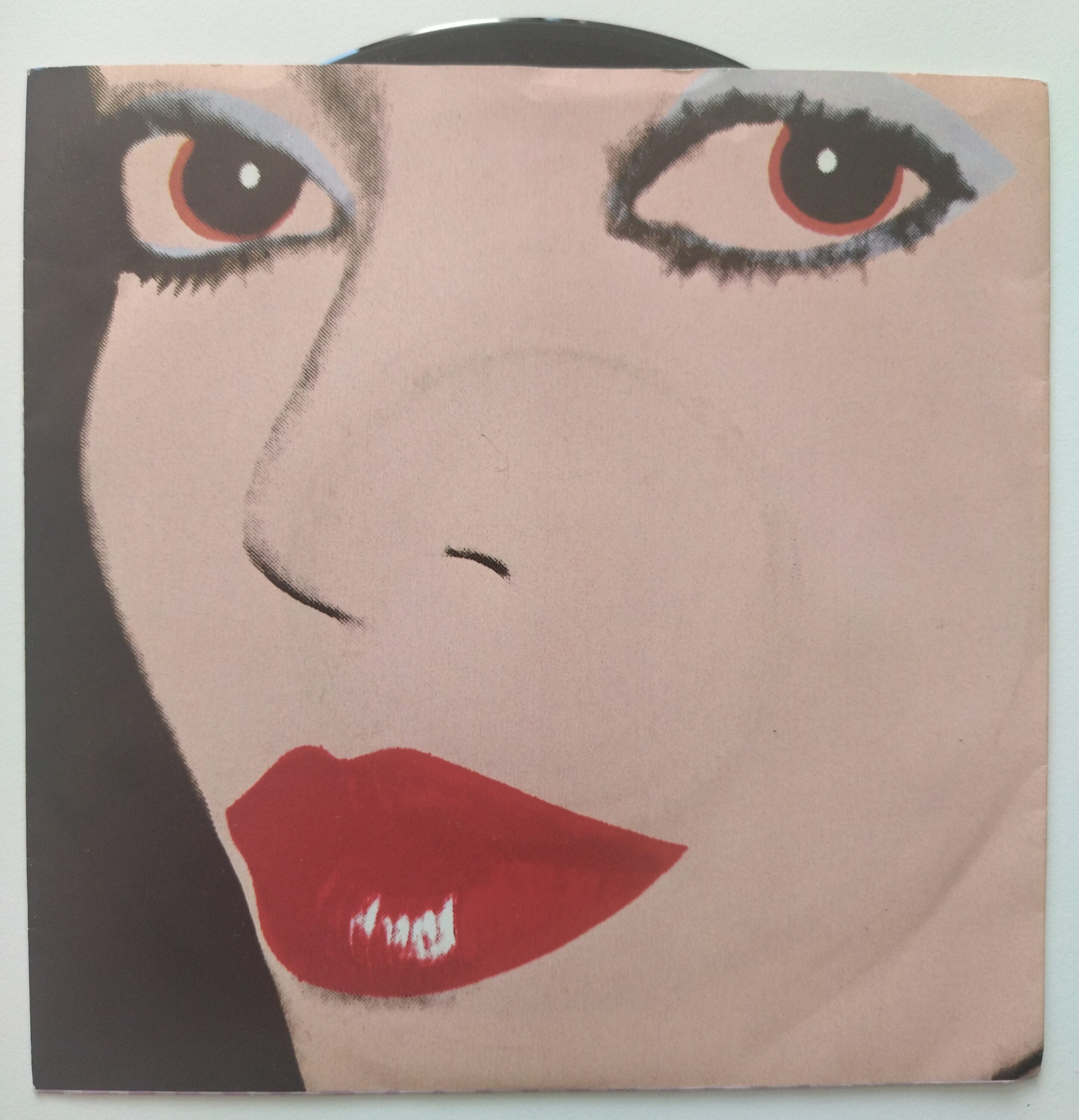

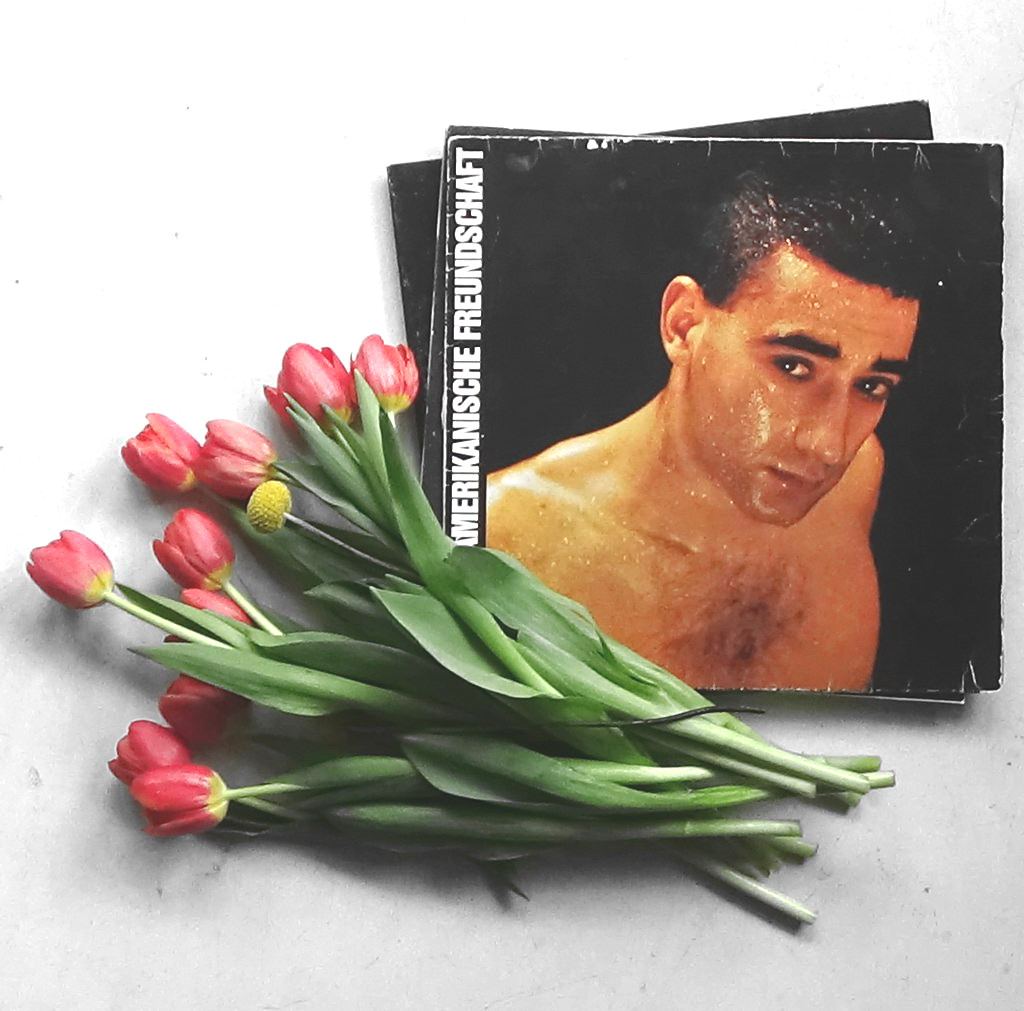

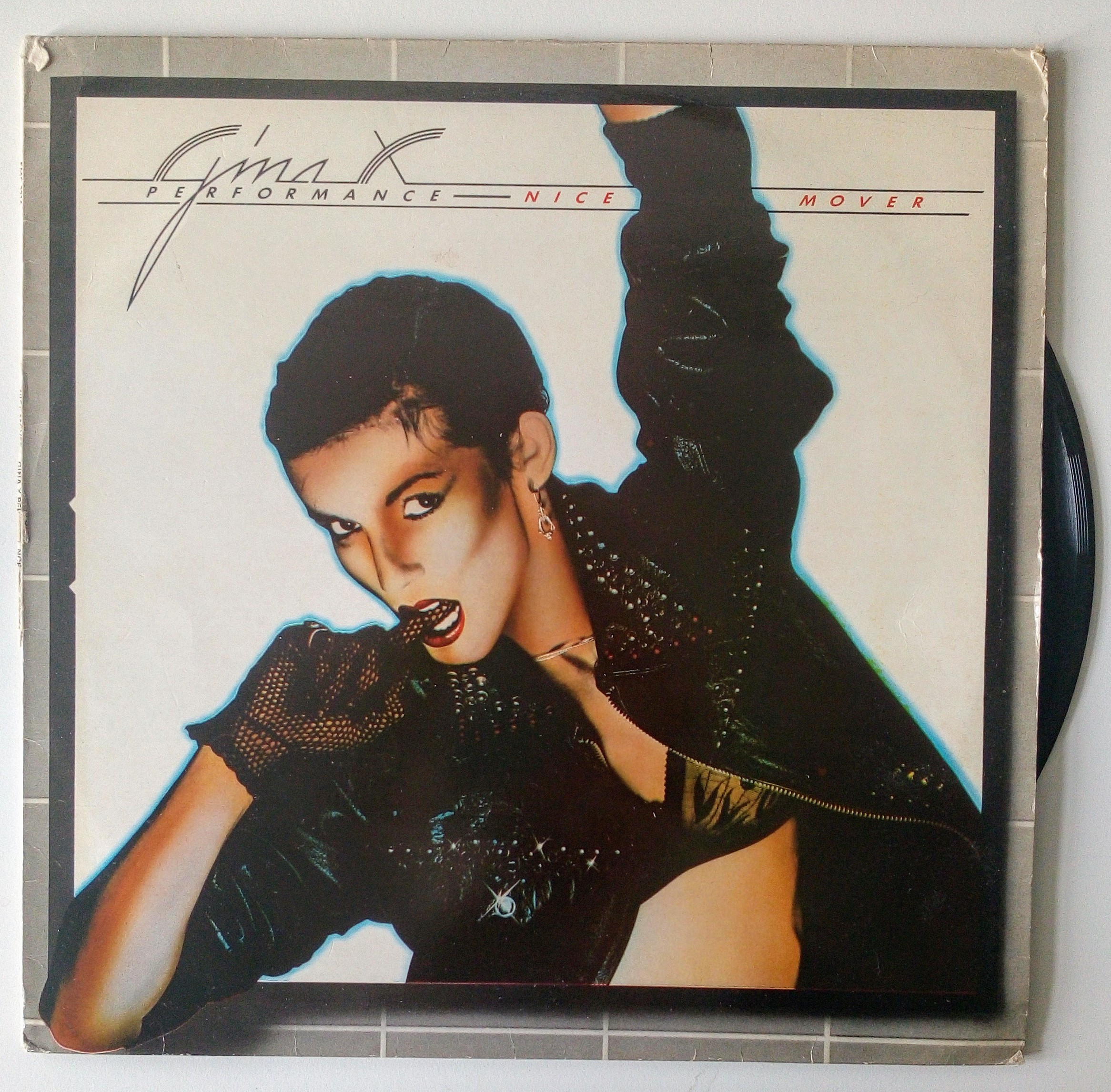

Crucially, this was propagated via popular artforms that circulated widely; poster art, science fiction books, album sleeves, product and fashion design. Ultimately, Ashur’s work represents the last gasps of visual culture spawned by the psychedelic revolution. His paintings are at once personal and universal, microcosmic and macrocosmic. In his own words, the paintings he made were: “complex dramas, the plots of which vary from cosmic to molecular” that reveal “immutable laws of crystal formation at the centre of exploding stars” and “the persistent tendency to order (…) abiding within the heart of chaos.”[x]

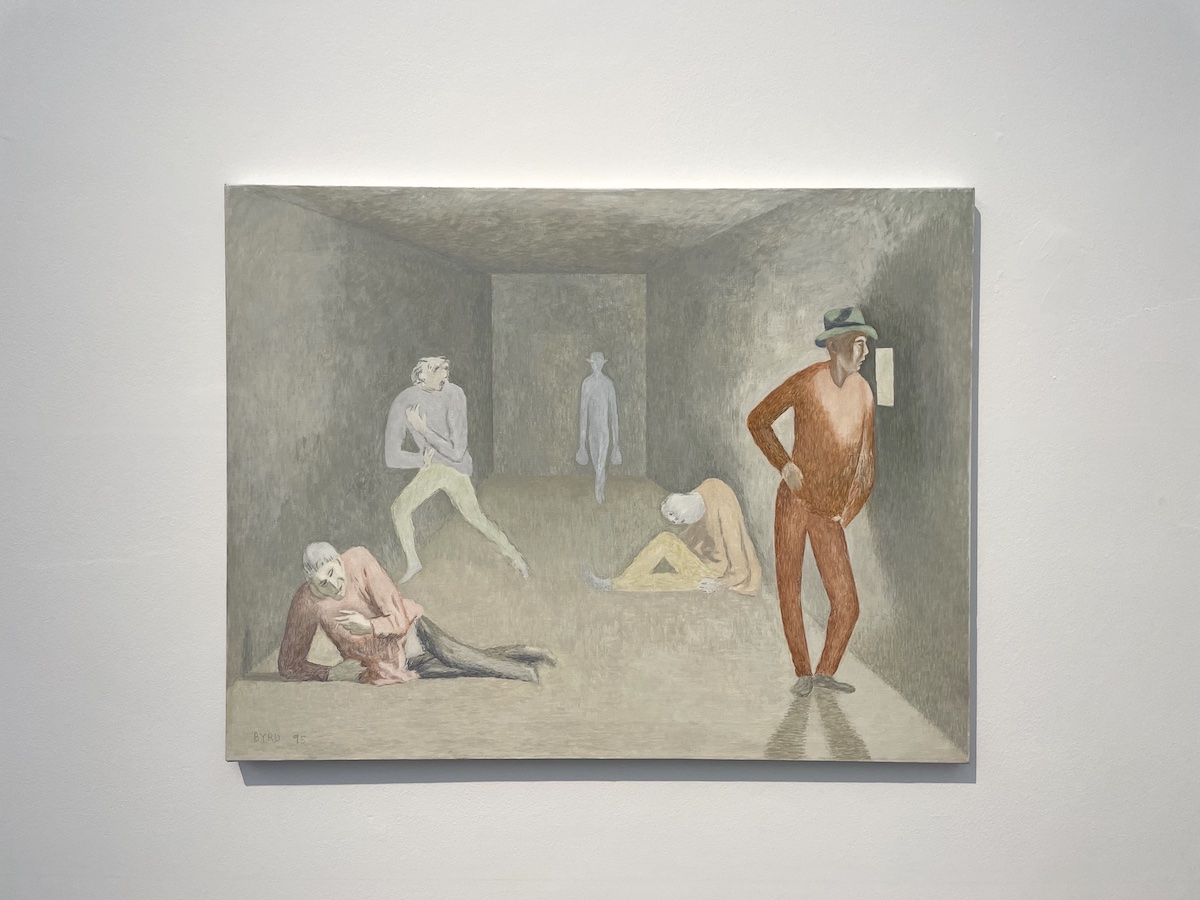

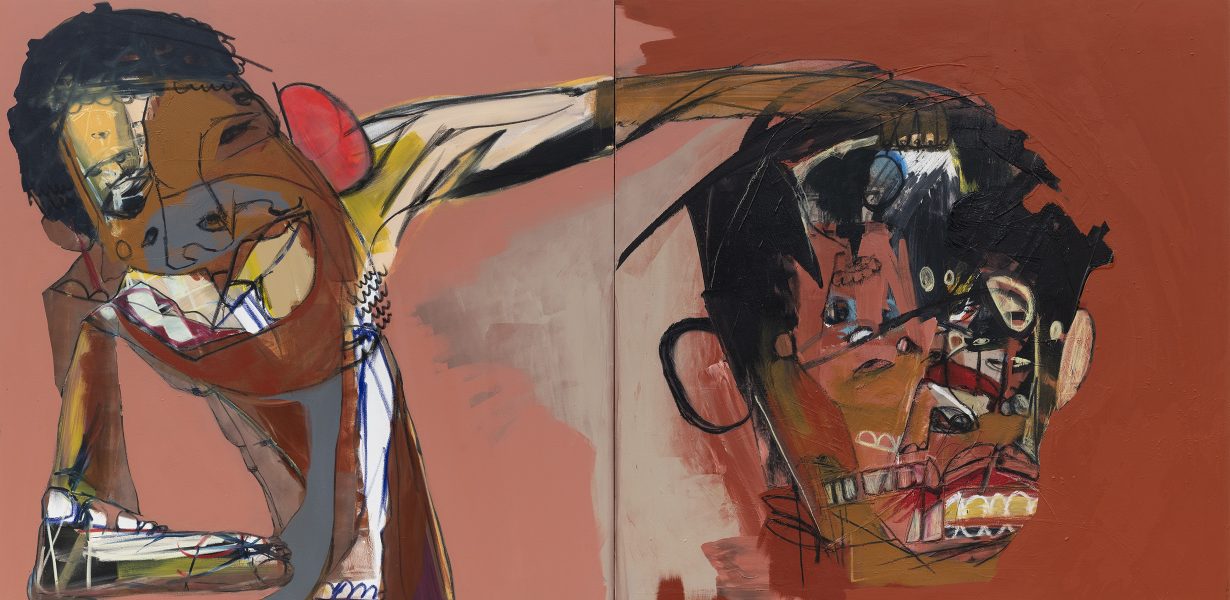

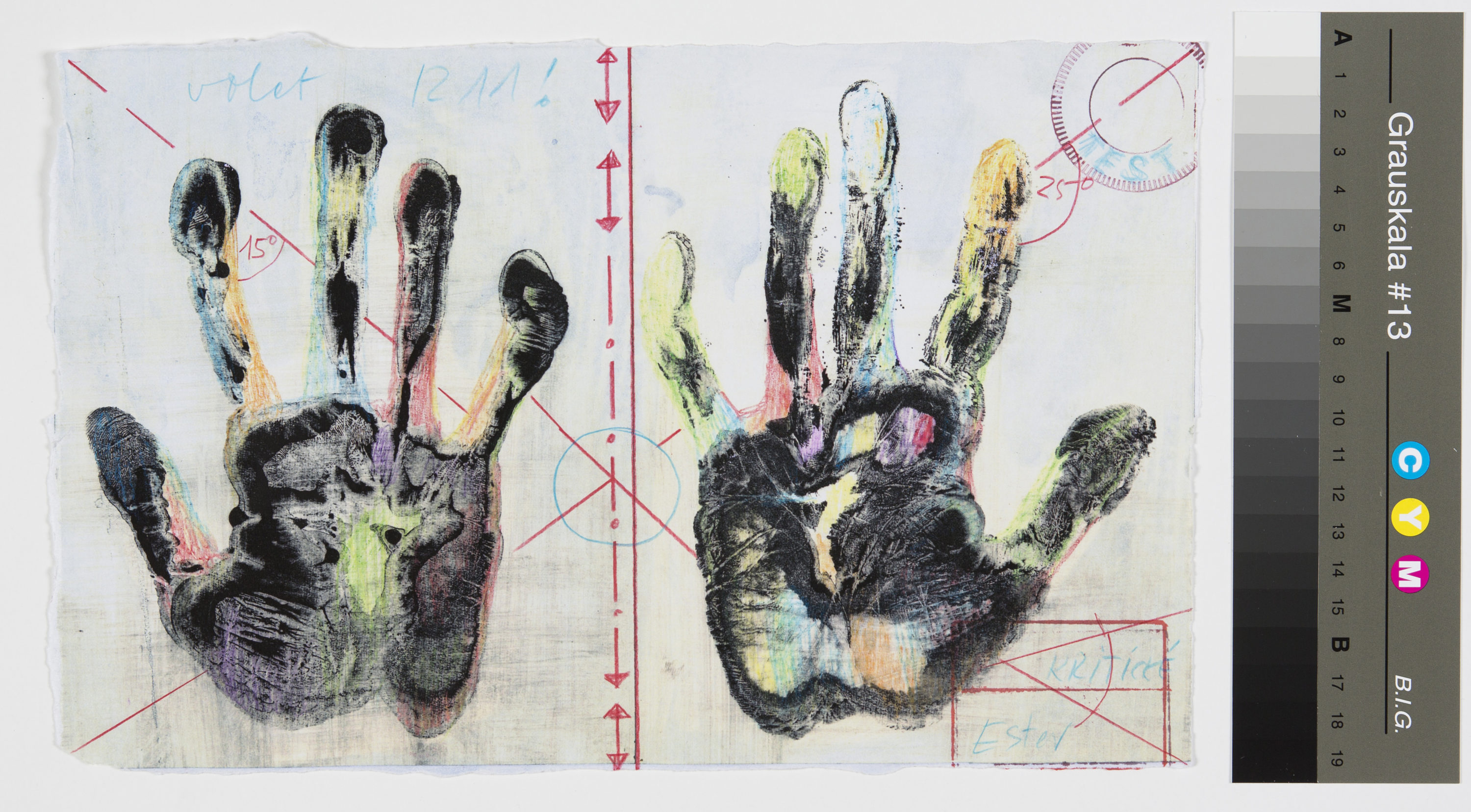

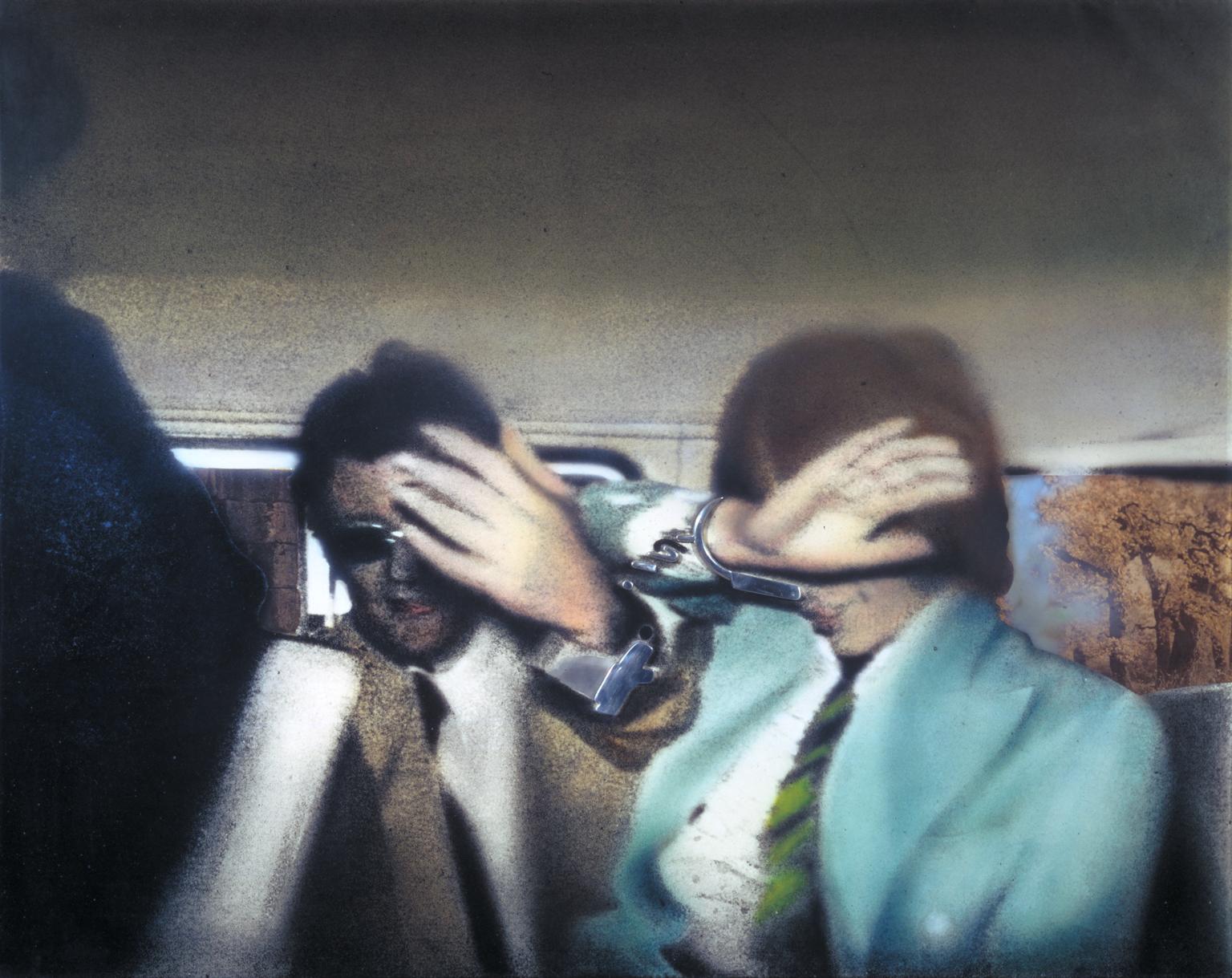

Ashur enjoyed considerable success in Ireland and Europe from the early 1970s but as the 1980s progressed Ashur’s currency waned rapidly. The doom-laden atmosphere pervading Ireland in that leaden era was conducive to aesthetic tendencies typified by Rita Duffy, Brian Maguire, Patrick Graham and others[xi]. Neo-expressionism, and all it represented, was anathema to Ashur’s creations — an excess of airbrush, fastidiousness and procedural detachment. Instead, directness, muscular authenticity and existential angst was embraced by artists who sought to sidestep (what they saw as) an excessively cerebral and etiolated approach to making art. Inevitably, Ashur’s technical methods -and the fact that he actually made a virtue of artifice- led to his space age capricci being viewed as excessively slick and superficial.

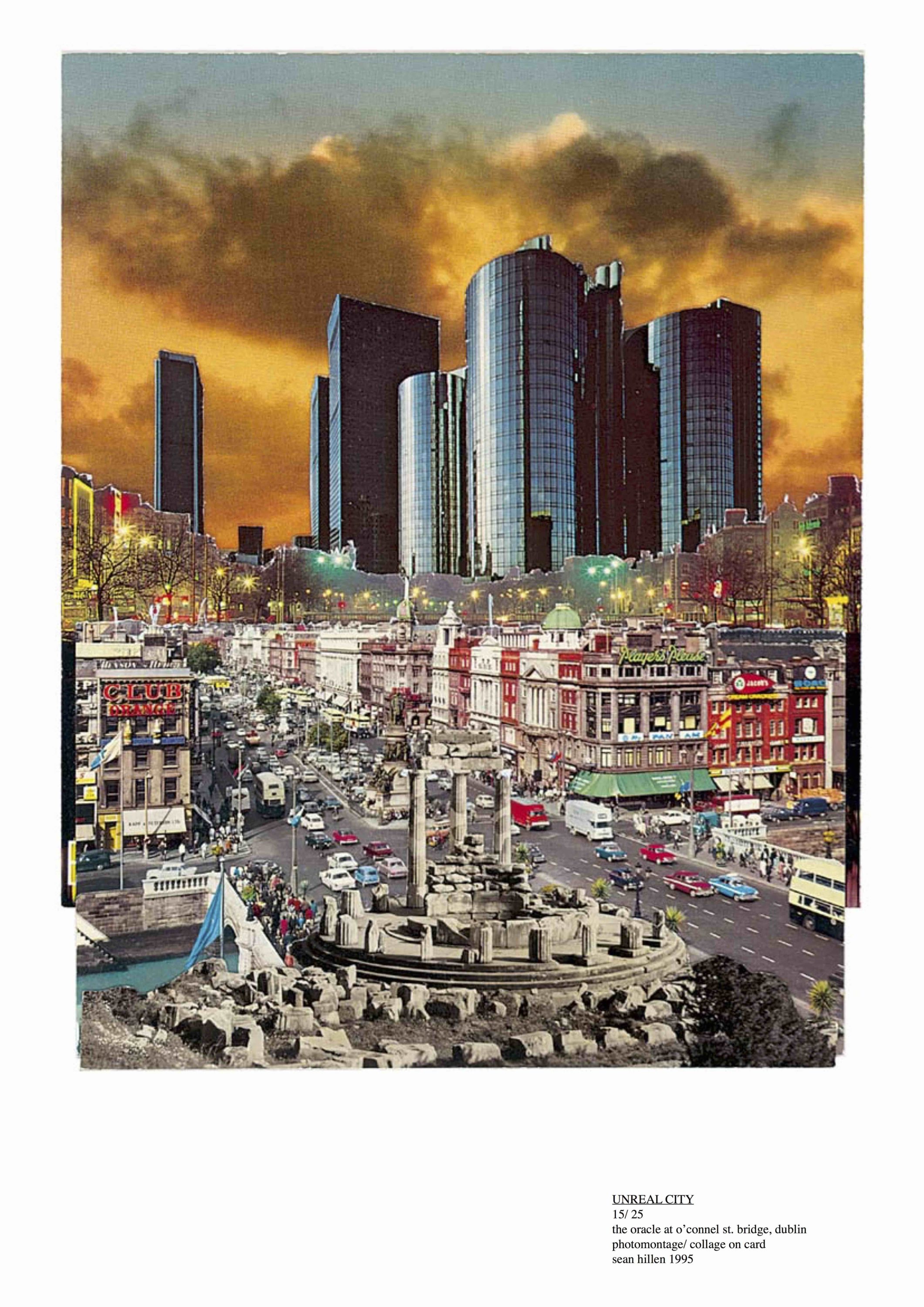

By the mid 90s his work had receded from view. The bio on his -now defunct- website indicated that he stopped producing work in the early 90s. The self-promotion that he had actively engaged in, which saw him give frequent interviews ceased. Crucially, this was a period in which contemporary Irish art moved rapidly forward, falling in step with other European countries whilst also focusing upon the repercussions of post-colonial fallout. Initially viewed as valid, his works soon came to be relegated to basements and storage units. Although held in several collections throughout the state, his works have -until very recently- been rarely displayed. This is because Ashur’s works are an anachronism; so totally of their moment that they cannot function outside of it, which is the very same reason why they were once so appreciated. They now appear to us as anomalies and cannot be conveniently categorised into any particular canon.

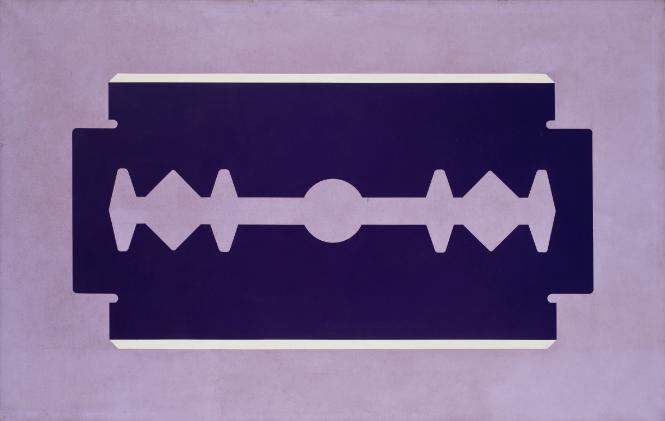

Comparisons with other artists who emerged around the same period -but succeeded in maintaining reputational capital- are useful here. Take for example Robert Ballagh who although worked in a different idiom initially worked in a manner that shared parallel with Ashur. As the major retrospective exhibition that took place at the RHA almost 20 years ago demonstrated, Ballagh’s Pop tendencies tempered as the years progressed. His Razor Blades and Iced Caramels were made alongside images that would best be described as Agit-Pop: marching crowds and paintings of IRA mugshots. By the 1970s Ballagh was making polemical pastiches of works by Goya and Delacroix and went on to work in portraiture, all of which sealed his place within the canon. Ashur’s images certainly became more complex and baroque and grew in scale, but his modus was one of repetition. For an artist working mainly in the context of Ireland in the 1980s and 90s this proved detrimental, particularly when his gallery closed permanently which foreclosed the possibility of recruiting new collectors for his work. Faced with all this Ashur ceased making art in the 90s and withdrew from the art scene. His absence in the 90s and late 00s undoubtedly contributed further to his being occluded. Unlike several other artists who emerged alongside him and achieved similar success Ashur has not been included in survey shows that seek to summarise the culture of the period in which he had at one time been a prominent figure.

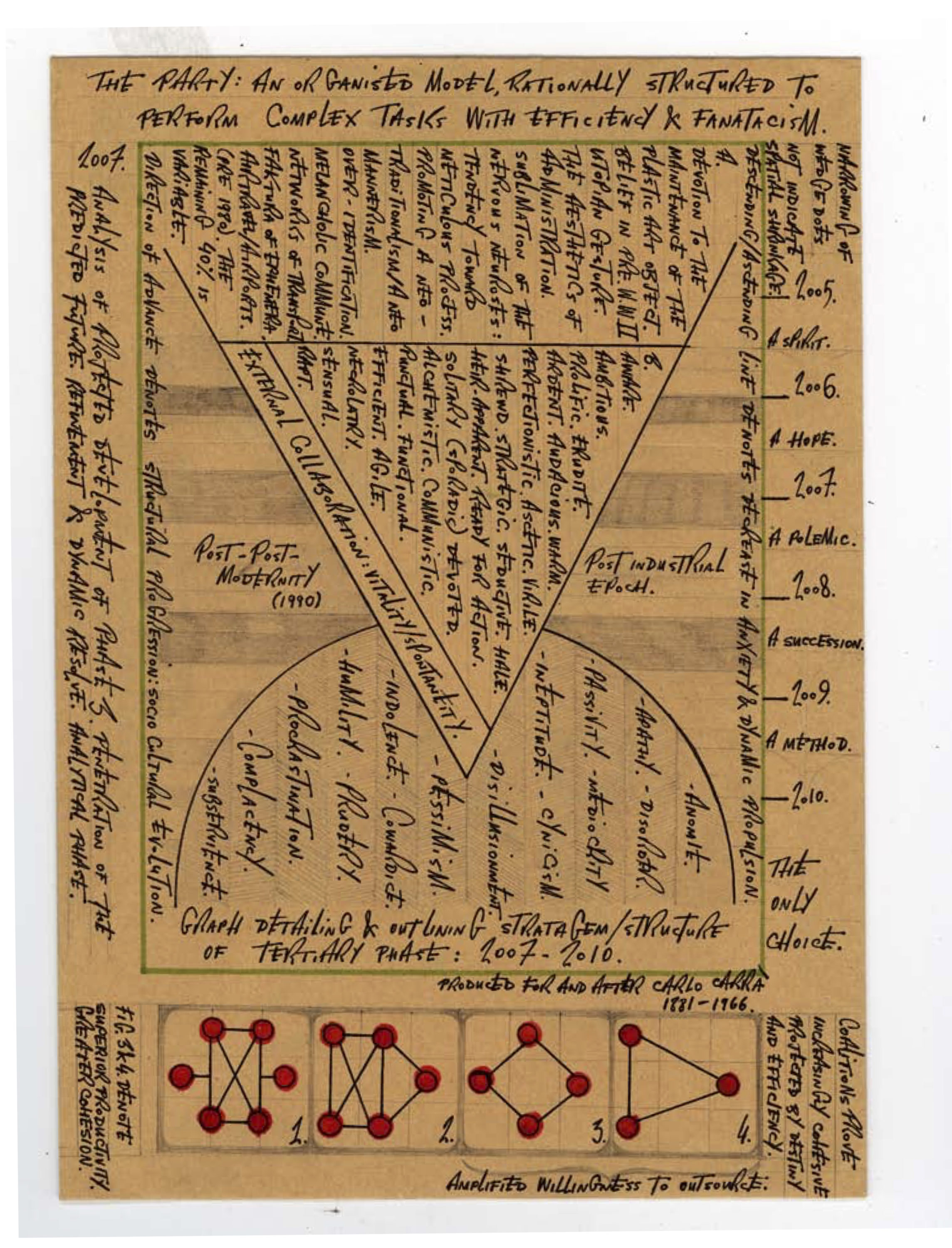

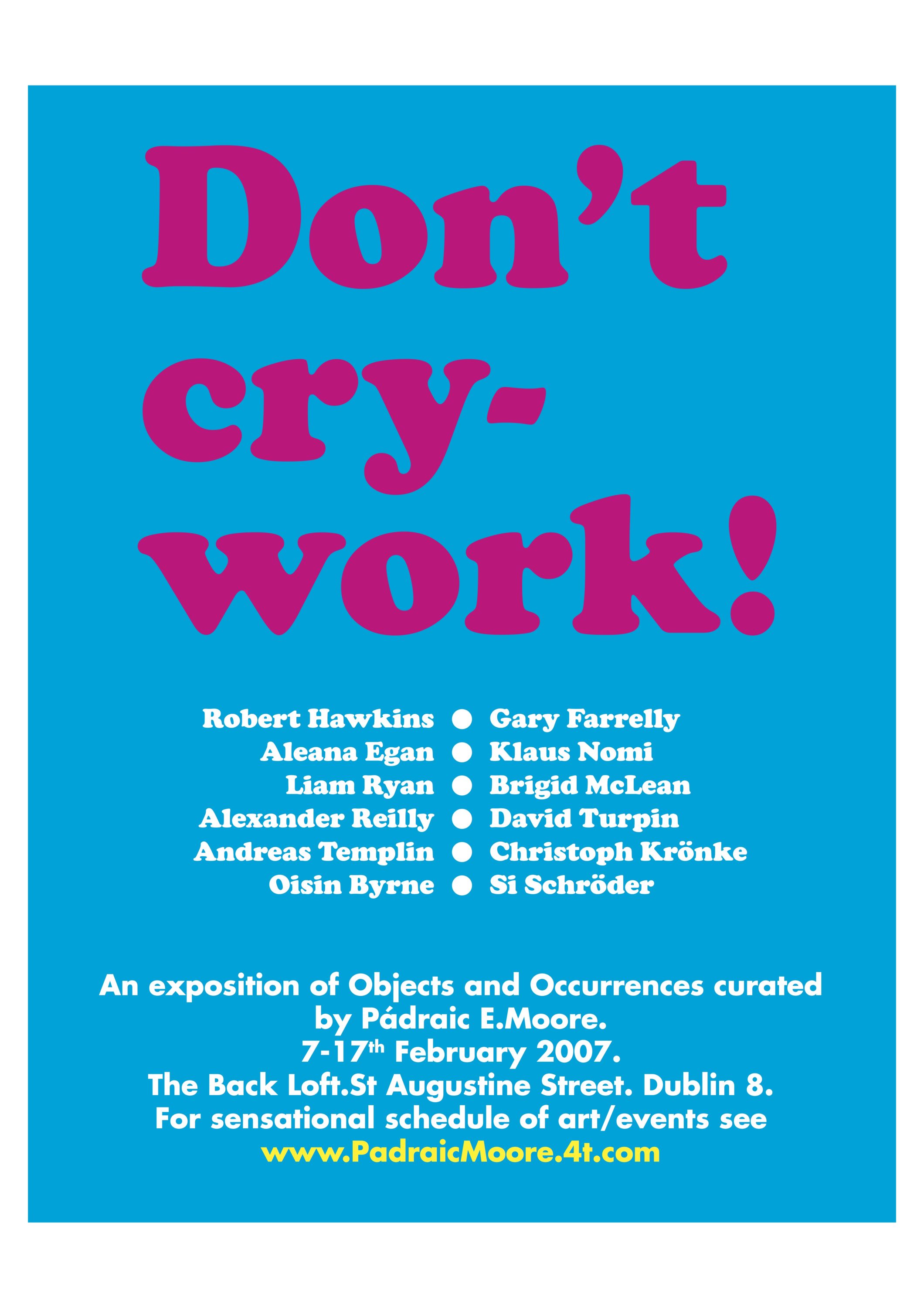

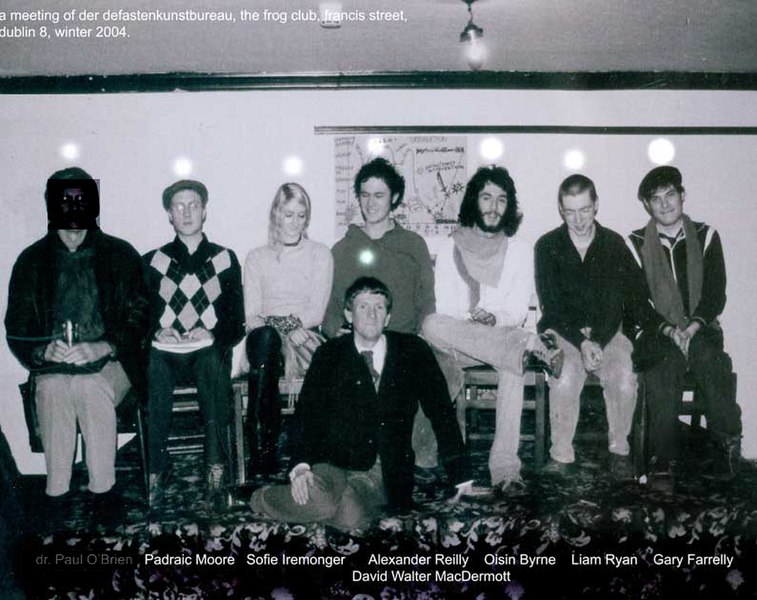

It is notable that some of the obstacles that hampered Ashur’s career continue to shape the cultural landscape here. The ‘too much too soon’ syndrome is injurious to an artist working anywhere, but negative effects are amplified in a context where private collectors here are few and institutions rarely make repeat acquisitions. Despite the connectedness afforded by telecommunications and cheap flights we remain fundamentally isolated. This results in artists running out of creative and financial prospects and avenues to present their work, unless they actively seek out opportunities elsewhere. Increasingly large numbers of artists reliant on limited resources creates a subcurrent of scarcity and gives rise to a competitive individualism that erodes collegiality within artistic communities.

Ashur’s meteoric progression was typical of an age when a succession of movements flourished and eventually superseded each other. Technological advancement and an appetite for novelty led to rapid cycles of change in which the visual arts played an integral part. The fate of this individual’s oeuvre demonstrates more universal realities. Early commercial success and critical acclaim are no guarantee of a place within the canon and the factors shaping the latter are often arbitrary and subjective. On a local level, Ashur’s case casts light on a network of individuals and cultural entities that no longer exist, whilst pointing to some of the enduring challenges Irish artists continue to face.

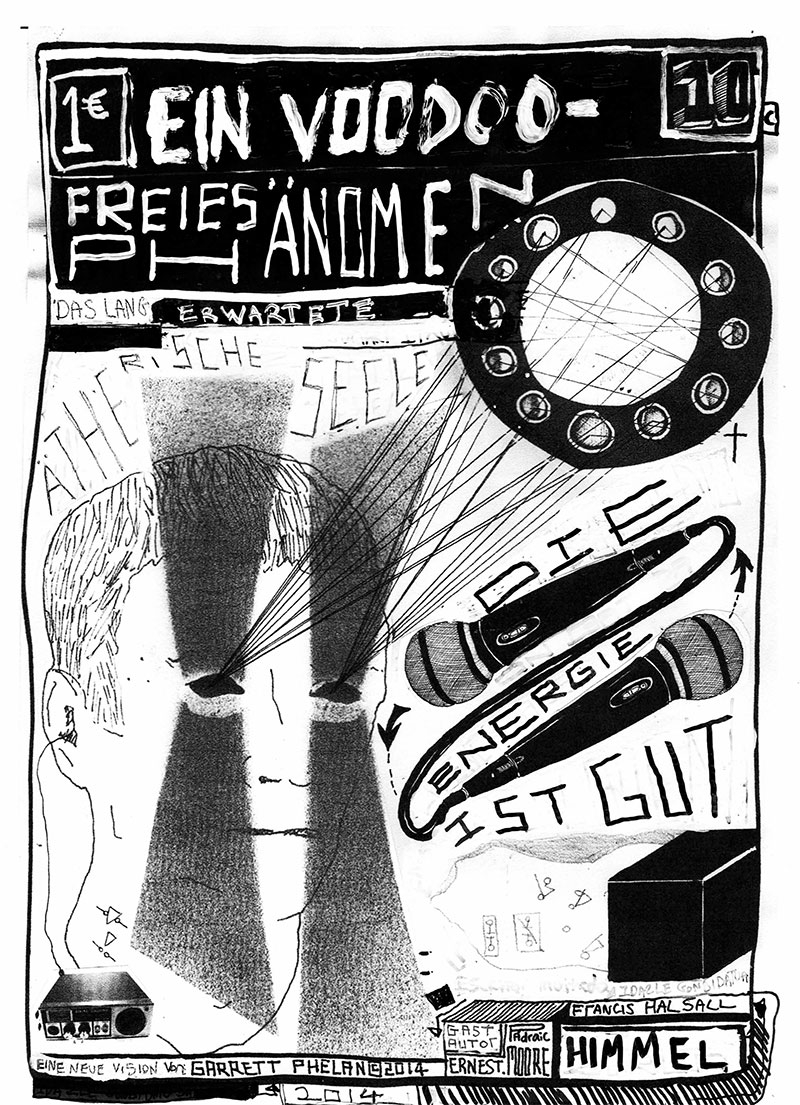

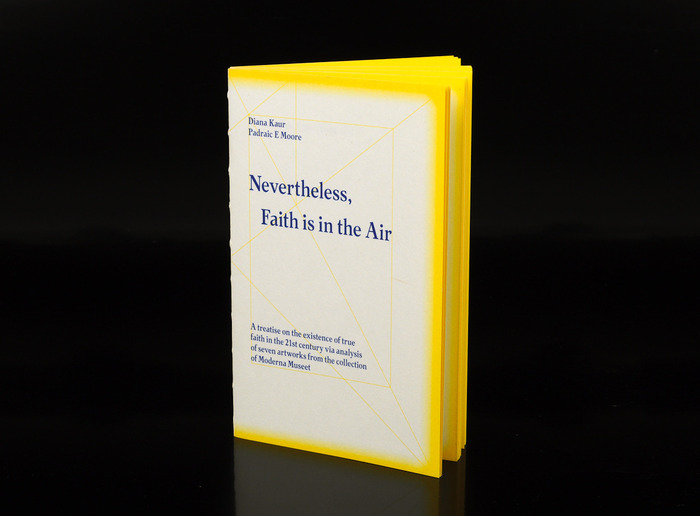

-Pádraic E. Moore, Spring 2025

[i] S.B.Kennedy, Irish Art & Modernism, 1880 – 1950, exh.cat., Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, 1991, p.118

[ii] ibid

[iii] Peter Shortt’s book, The Poetry of Vision, is an excellent study on the subject of the Rosc exhibitions.

[iv] https://magill.ie/archive/one-mans-art

[v] Interview with Martin Gale, January 2025.

[vi] In addition to the more aspirational and literary reasons for this name change, it is worth noting that there was already another artist named Michael Byrne (1923–89) who was a proponent of the same hard edge formalism that was so in vogue at the time. The name change may also have been a pragmatic strategy of differentiation..

[vii]Lawrence Alloway highlighted the existence of this movement in a Guggenheim Museum exhibition entitled The Shaped Canvas, which took place in 1964–65 and featured works by Richard Smith, Frank Stella, and several others.

[viii] https://imma.ie/magazine/curators-blogs-christina-kennedy-on-david-hendriks/

[ix] Ashur represented Ireland in major exhibitions that were prestigious at the time but do not exist anymore, such as the International Festival of Painting in Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, in 1981; his contribution was voted the most popular work in the exhibition by public vote.

[x] Michael Ashur exhibition press release, 1991.

[xi] These can be viewed as Ireland’s answer to Neue Wilde or Transavanguardia